By now, enough has been written and said about the intensifying fusion between politics and religion to know something is amiss. That much is clear.

Rarely a week goes by without another media report on the increasing interplay between religious and political convictions in America. In one such article, John Fea, chair of the history department at Messiah College near Harrisburg, highlighted the increasing frequency of candidates for office who speak without any “distinction between political argument and spiritual warfare.”

Notice, however, that most commentators are pointing their cautionary fingers at someone else who has fallen into this trap. In our experience, this can be far harder to see in ourselves. Maybe we can give ourselves a bit of a break, though, since this kind of tension has been going on for many centuries.

A conflict long with us. Christianity and politics have always had an uneasy relationship. During the time of Jesus, the people’s ability to recognize Israel’s messiah was hampered by their own expectation that the messiah would be a political deliverer, throwing off the oppression of Rome.

It’s not hard to see why the masses in Israel, holding this view of a political messiah, found Jesus to be disappointing.

With the exception of the instance where Jesus called Herod Antipas “that fox” and his response to the duplicitous question, “Is it lawful for us to give tribute unto Caesar, or not,” it’s remarkable that politics had so little a place in the recorded words of this man—who would, of course, eventually acknowledge before the reigning political leader, “My kingdom is not of this world.”

Jesus certainly had strong views of what a just society should look like, but his vision for the transformation of society was never a partisan political push for one or another party to assume power; this is why that later conversation reflected Pilate’s genuine confusion as to how the explicitly apolitical Jesus had caused such a reaction among the Jewish establishment—since he was clearly understood to be no real threat to Rome. (And his vision was such a contrast with the political and violent agitation of the Zealots.)

The sacred texts of other faiths also mention concepts that are arguably politically related. This ranges from encouragement to seek leaders who are honest to more ancient explorations of divinely-inspired law-giving and warnings about how the wickedness of leaders and the people can lead to bondage and civilizational decline. Examples of leaders giving up political power and devoting themselves to religious revival and conversion are core to many religious accounts, and they are too often neglected today. Simon Zelotes dropped being a “fisher of political objectives” to become a full-time “fisher of men.” And in Latter-day Saint scripture, political leaders Alma and Nephi “yielded up the judgment seat,” stepping away from their political positions once they realized the people’s problems were soul-level, not vote-level. These passages tell us that the people in the time of Nephi had become “a stiffnecked people, insomuch that they could not be governed by the law nor justice,” and in Alma’s time, he saw “no way that he might reclaim them save it were in bearing down in pure testimony against them.”

Could the problems facing our own nation be similar as well? If the problems are indeed in people’s souls, can we see how politics simply becomes a constant exercise in loud flailing that achieves very little?

The lust for power. Rather than step away from our sweaty and insecure grasp on power, however, we see in our country today the reverse tendency: clinging even more to the judgment seat rather than inviting our neighbors to the healing and rest that come from loving God. When it comes to deep soul-level problems among a people, is there really any other way that offers true hope for the country? In our constant political frenzy, it becomes hard to recognize the more subtle flavor of God’s influence.

This explains our concern at seeing so many Americans, including Latter-day Saints, taking the devotion they formerly applied to faith and transferring that devotion to politics and politicians. One of our own cherished leaders of faith, Richard Scott, once underscored the danger involved by noting that the subtle manifestations of inspiration “can be overcome or masked by strong emotions, such as anger, hate, passion, fear, or pride.” As he went on to explain, “When such influences are present, it is like trying to savor the delicate flavor of a grape while eating a jalapeño pepper. Both flavors are present, but one completely overpowers the other.”

However enjoyable these strong emotions are, what else might they be overpowering inside us and around us?

Like Judeans in the time of Isaiah, Americans sometimes seem to be seeking deliverance in political activity that, like a jalapeno, is hot with emotions like hate, fear, and pride. In our constant political frenzy, it becomes hard to recognize the more subtle flavor of God’s influence.

And in our day, it’s precisely this kind of higher influence that millions of believers—Christian and otherwise—are convinced that our increasingly-ungovernable nations need.

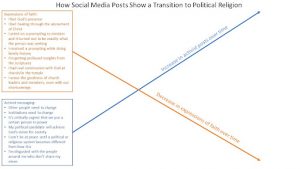

Watching our own trajectory. This transfer of our devotion from God to politics is perhaps most visible among social media users, whose social media posts over time often evolve from a focus on faith and personal improvement to a focus on activist messaging and denouncing political opponents.

Compared with expressions about the movement of God’s hand in someone’s life and what someone is learning, we can all witness a distinct shift when these messages become increasingly strident demands that others change, and insistence that their own political ruler is the rightful one to save the day.

Is that what you think? Is our enthusiasm for politics as believers stronger than our higher covenantal commitments as people of faith?

We began this article by acknowledging that these questions may be much harder to answer in our own lives—than the people we observe around us. So, here are some other helpful indicators that we might use as a litmus test for our own political-religious balance of priorities.

- When you ponder the question of how God’s higher purposes are to be achieved among humanity, your thoughts immediately turn to political figures and parties.

- You prefer explosive political commentary as a better guide to reality than anything else, including calmer, less “entertaining” teachings from ancient and modern prophets.

- You see people’s political views as the most important aspect of their identity.

- You can only see good in our political allies and only bad in your political opponents.

- You view politicians in one party as somehow favored by God—even countenancing messianic and priestly terms like “anointing” and “savior” when discussing them.

- You fantasize about defeating, humiliating, and silencing people you disagree with rather than loving and persuading them.

- You scour sacred writ largely to identify villains—who most often seem to resemble people you disagree with politically.

Every one of these questions is ultimately aimed at considering the extent to which our political views are answering yearnings in our souls that should instead be answered by the love of God and our neighbor.

Drawing clearer lines. American believers as a whole would benefit from making clearer distinctions between questions of religious teaching versus public policy. While it’s true that they sometimes overlap, that is most often in the eye of the beholder and increasingly fraught, wherein friends who express opposing views on questions like monetary policy or net neutrality mistakenly end up thinking each other’s soul is in jeopardy.

The consequences for excessive focus on political issues in faith communities can be significant. In a new report by political scientists David E. Campbell and Geoffrey C. Layman of the University of Notre Dame and John C. Green of the University of Akron, they argue that one reason for the growing secular trend is because politics has invaded faith, making it often unpalatable for those who do not share specific political beliefs. As the lead author put it, “I would say to churches, on both the left and the right, that if you want to bring people back to the pews, you want to stay out of politics.”

Political conviction is a fine thing, but our hope is that fellow religious Americans can learn to treat partisan politics like a second language, only used if and when necessary, and never at the expense of their higher commitments of faith and family.

Our hope is that in upcoming election seasons, we can take time to reflect on the source of our political activity, whether it comes from a place of peace or anger, love or loathing, spiritual poise, or social turmoil. For American believers who are both politically active and seeking to convey more of God’s influence into the world, these are questions with real consequences for our spiritual well-being as well.

It’s helpful to keep reminding ourselves that a babe born in a no-name backwater shook kingdoms. While it’s true God occasionally works through political leaders (Cyrus, for example), more often than not, he works around them. As the Psalmist says, “Put not your trust in princes, nor in [human beings], in whom there is no help.” Scripture instead directs our attention towards a God who can and does accomplish his purposes through the humble and seemingly powerless.

The post Has Politics Become Your New Religion? appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →