The Know

Many passages in the Old Testament—but especially in the Psalms—refer to grasping the Lord’s right hand.1 For example, Psalm 139:10 describes how the Lord would lead the psalmist by the hand “and thy right hand shall hold me.” Psalm 63:8 states, “My soul followeth hard after thee: thy right hand upholdeth [held] me.” Psalm 73:23–24 similarly describes the psalmist following the Lord into a sacred space as he grasps the Lord’s hand: “I am continually with thee: thou hast holden me by my right hand. Thou shalt guide me with thy counsel, and afterward receive me to glory.”

These passages can be illuminated by an understanding of the concept referred to as a divine embrace or divine handclasp, which shows up frequently in ancient art, writings, and rituals. Hugh Nibley began drawing Latter-day Saints’ attention to this material in the 1960s–70s2 and inspired younger scholars like David Rolph Seely, Stephen D. Ricks, Matthew B. Brown, and David M. Calabro to further study this concept as it is expressed in the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and throughout the ancient world.3

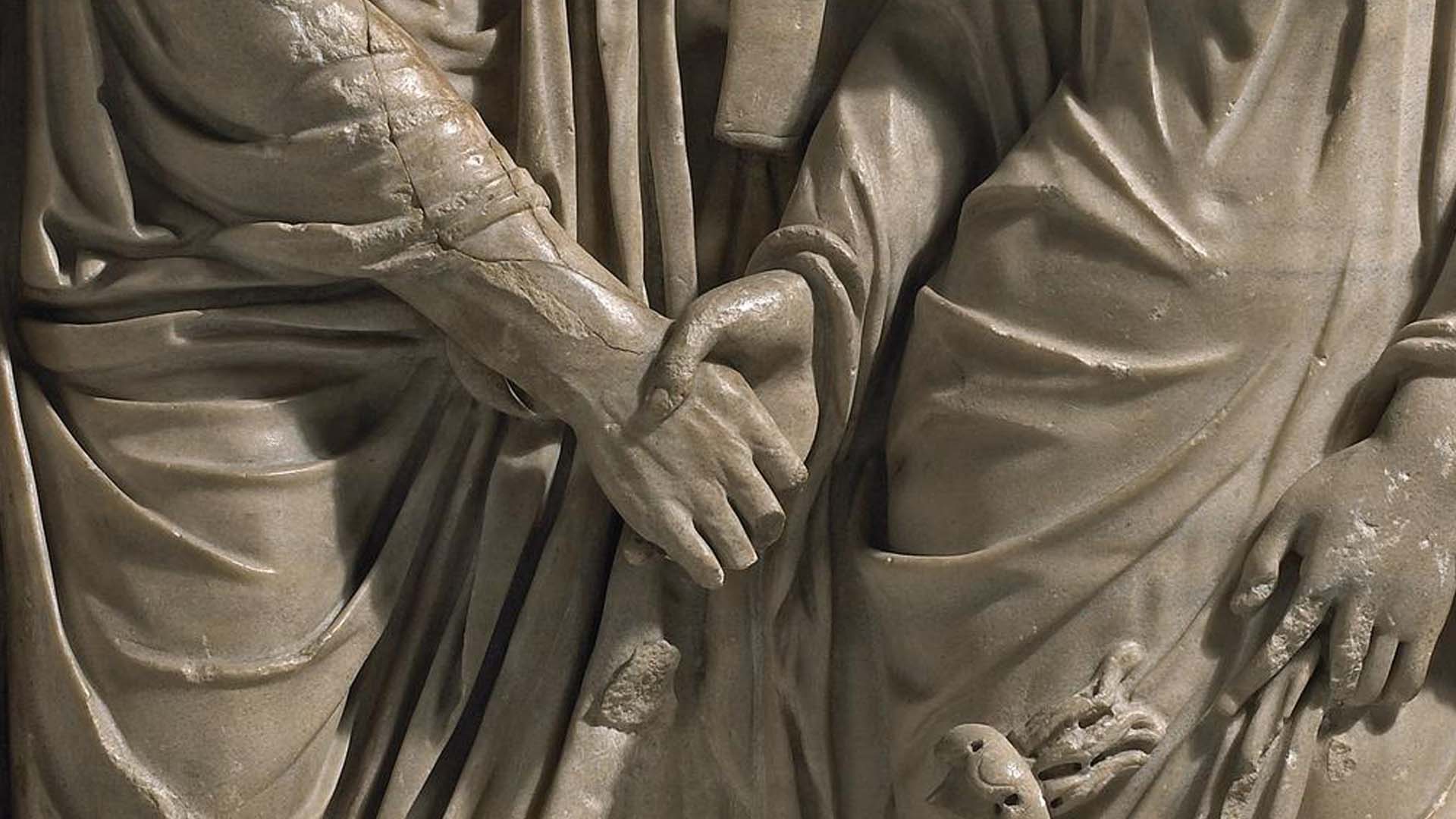

Early depictions of a deity grasping the hand of a king or temple petitioner are found in Egyptian, Roman, and early Christian artwork.4 These scenes are especially prevalent in “the most sacred and (to the unauthorized) inaccessible precincts of the temple” in ancient Egypt and may relate to coronation or receiving the king “into the presence of the gods.”5

In early Christian writings, Hugh Nibley has found traces of a handclasp offered by the Lord to His apostles. They performed this handclasp while forming a prayer circle, and Jesus is recorded as linking this handclasp to His coming crucifixion: “Then he gave them certain signs, and he took their hands and said, Know my suffering and thou shalt have the power not to suffer. I will be crucified so that you won’t have to be. You will be merely in token.”6

One prominent example is found in the Utrecht Psalter made in the ninth century AD. Brown pointed out that in this illuminated manuscript, “The king of Israel is shown meeting face to face with the heavenly King (and what may also be the divine council) at the parted veil of the temple. In Psalm 27:10, the king of Israel says that ‘the Lord will take [acaph, take in or receive into] [him] up’; in the Utrecht Psalter, the Lord is shown reaching down a stairway and grasping the king by the right hand, possibly to induct him into the heavenly assembly.”7

Several scholars have proposed that this divine handclasp may have been an ancient temple ritual in which a temple priest stood as a proxy for the Lord.8 Brown specifically pointed to Psalm 89, in which the Lord describes anointing a king and establishing (literally “fastening” or “attaching”) him with His hand (see Psalm 89:20–21): “The Lord says in Psalm 89 that it is He who anoints the king, though it is clear in other texts that this was actually carried out by a priestly proxy (see 1 Samuel 16:1; 1 Kings 1:39). A ceremonial handclasp, therefore, could conceivably have been accomplished in the same manner.”9

Based on Psalms 73 and 139, Calabro determined that “we see that both God and the Psalmist use their right hands. This would suggest that the participants in the gesture are facing each other, as we do when we shake hands” and that this “is compatible with the idea that the divine handclasp was performative in nature.”11 Because these scriptures mention the recipient being received by the Lord, it appears that it was done “in the … sense of one party pulling the other inward” rather than walking side-by-side with the petitioner.11

The meaning behind this ritual grasping of the right hand may be multifaceted. Nibley noted that handclasps could be used as a sign or token conveying “recognition and acceptance of those who were once apart.”12 As Stephen D. Ricks has observed, it often appears while leading a petitioner to a more sacred and holy realm in both Christian and Mediterranean art.13 It also appears in a covenant-making context in Isaiah 41, 42, and 45, suggesting that it may have had such a context in the ancient temple.14 Finally, it may have “imparted a special status to the recipient, a status like that of a privileged servant or close family member.”15

The Why

As modern people read the ancient Hebrew scriptures today, they can learn much personally about the close association and familiarity with the Lord that was felt by righteous Israelites, especially in connection with temple texts such as the Psalms and other parts of the Old Testament. Regardless of whether or not a gesture of approach is described in every mention of “right hand” in the Old Testament, these words, especially of the Psalms, offer deep and meaningful illustration to readers of the Lord’s love for His people.16

Understanding the ritual connotations and theological background behind such a sacred embrace with the Lord can help readers understand the ceremonial significance of the Psalms and many other Old Testament passages relating to the ancient temple. Knowing this background can help all modern readers to appreciate much more deeply the love that faithful ancient Israelites had for their splendid temple in Jerusalem, which was built according to holy instructions and was honored and hallowed by those who worshipped the Lord there with clean hands and pure hearts (see Psalm 24:4).

In modern times, Latter-day Saint temple patrons can also receive new insights regarding this ancient element of temple worship as they serve and make covenants with the Lord there. As they do so, they can better understand and appreciate their own personal worthiness and standing with the Lord as one of His covenant people and, as the Psalmist, always seek to follow the Lord and be welcomed into His presence, both in this life and in the world to come.

Further Reading

Hugh Nibley, The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment (Provo, UT: FARMS; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005), 427–457.

Hugh Nibley, “Apocryphal Writings and the Teachings of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in Temple and Cosmos: Beyond this Ignorant Present (Provo, UT: FARMS; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1992), 264–335.

Stephen D. Ricks, “The Sacred Embrace and the Sacred Handclasp in Ancient Mediterranean Religions,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 37 (2020): 319–330; originally published in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of The Expound Symposium 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 159–170.

Matthew B. Brown, “The Handclasp, the Temple, and the King,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 421–426; originally published in Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, “The Temple on Mount Zion,” 22 September 2012, ed. William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 5–10.

David M. Calabro, “The Divine Handclasp in the Hebrew Bible and in Near Eastern Iconography,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 45 (2021): 37–52; originally published in Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, “The Temple on Mount Zion,” 22 September 2012, ed. William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 25–66.

- 1. For some non-Psalms examples, see Exodus 15:6; Deuteronomy 33:2; Isaiah 41:13; 42:6.

- 2. See Hugh Nibley, “Apocryphal Writings and the Teachings of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in Temple and Cosmos: Beyond this Ignorant Present (Provo, UT: FARMS; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 278, 296, 300–301, 304–305, 308–311, 315–317 (this lecture was originally given in 1967); Hugh Nibley, The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment, 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: FARMS; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005), 427–436 (the first edition was published in 1975).

- 3. See David Rolph Seely, “The Image of the Hand of God in the Exodus Tradition” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1990), 184–185; David Rolph Seely, “The Image of the Hand of God in the Book of Mormon and the Old Testament,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights That You May Have Missed Before (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 148–150; Stephen D. Ricks, “Dexiosis and Dextrarum Iunctio: The Sacred Handclasp in the Classical and Early Christian World,” FARMS Review 18, no. 1 (2006): 431–436; Matthew B. Brown, “The Handclasp, the Temple, and the King,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 421–426; David M. Calabro, “The Divine Handclasp in the Hebrew Bible and in Near Eastern Iconography,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 45 (2021): 37–52. The Brown and Calabro papers were each originally published in Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference, “The Temple on Mount Zion,” 22 September 2012, ed. William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 5–10, 25–66 (respectively).

- 4. See Stephen D. Ricks, “The Sacred Embrace and the Sacred Handclasp in Ancient Mediterranean Religions,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 37 (2020): 319–330, originally published in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of The Expound Symposium 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2014), 159–170; Calabro, “Divine Handclasp,” 42–47; Nibley, Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri, 29, 343, 345, 406, 445, 447, 456; Nibley, Temple and Cosmos, 105, 278, 300.

- 5. Ricks, “Sacred Embrace,” 323.

- 6. Nibley, “Apocryphal Writings,” 315, citing Acts of John 94–96.

- 7. Brown, “Handclasp, the Temple, and the King,” 424; see also fig. 2.

- 8. Calabro, “Divine Handclasp,” 37–38.

- 9. Brown, “Handclasp, the Temple, and the King,” 421–422. Matthew Brown argues that this gesture may have especially been used to coronate a king in the temple.

- 11. a. b. Calabro, “Divine Handclasp,” 39, 47.

- 12. Hugh W. Nibley, “On the Sacred and the Symbolic,” in Temples of the Ancient World, ed. Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1994), 558; reprinted in Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 2008), 363.

- 13. See Ricks, “Sacred Embrace,” 323–326.

- 14. See Calabro, “Divine Handclasp,” 39–40.

- 15. Calabro, “Divine Handclasp,” 47.

- 16. As Calabro, “Divine Handclasp,” 38, noted, “Whether or not a concrete gesture is described, biblical references to the divine handclasp are profound expressions of close interaction with Deity, a concept that was rooted in the rites of the temple.”

Continue reading at the original source →