Over the past several months, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has again found itself at the center of a number of media controversies, from Hulu’s dramatic storytelling in Under the Banner of Heaven to the AP’s recent attempted exposé on the Church’s efforts to minister to families where abuse was tragically taking place. While the various events and productions have taken center stage in our collective awareness, there is something else taking place in the broader public response to all of this that has stood out to us both—and which we believe deserves some additional attention.

We have noticed the striking divergence in reaction to both tragedies—murder and abuse—and that it seems to depend mostly on where people already were oriented in their feelings towards the Church. In the first case, former members no longer friendly to the Church loved the show and touted its authenticity, while active (and even some inactive) members decried its inaccuracies. A similar disparity occurred in response to allegations of bishops and other church representatives mishandling abuse reports—with former members often raging about the accusations but asking few questions about their legitimacy, and current members mourning the revelations of abuse but asking questions about their context, sources, reliability, and so on.

In one sense, this bifurcated reaction to these media and news reporting events has been fairly predictable—with one’s relative curiosity fairly closely tied to one’s deeper, pre-existing feelings of affection or revulsion. In the wake of that, those already holding unfavorable views of the Church run with the narratives provided, unquestioningly and uncritically holding them up as hard evidence for what they already believe about the Church. Meanwhile, faithful Latter-day Saints point out the inaccuracies in these depictions of the Church, arguing for larger or more nuanced context to be taken into account and contending that reality is most assuredly not as it is being presented.

Much of that should not, perhaps, surprise any of us. After all, we tend to defend that which we love and value. And the opposite is true for those things we dislike and hold in suspicion—where we are more likely to pile up evidence to justify our aversion than we are to dig deeper or do anything that might unsettle our distaste or contradict our established views.

This sharply differential response is further exacerbated as both sides tend to draw on very real and very personal experiences as primary evidence to support their perspective. Many who find merit in such media depictions feel they have indeed been harmed in some way and, given such experiences, feel the true nature of the Church as an oppressive institution and a “systematic abuser” is being accurately represented. At the same time, those who question the veracity of the negative narratives advanced by those in the media tend to argue that popular depictions of the Church are nothing like the faith community they personally experience on a regular basis. Instead, they bear witness to a Church that is an active force for good in the world, an institution that is continuously and actively fighting against evil of many kinds, certainly including abuse and violence. Former members no longer friendly to the Church loved the show and touted its authenticity, while active members decried its inaccuracies.

In many ways, the answer to such questions seems obvious: Different people have different experiences, and those experiences, in turn, lead to their different perspectives. This happens among different children raised by the same parents, so it probably shouldn’t surprise us to see the same thing happening with different members of the same parent church.

But there is more going on here, we believe, than mere confirmation bias—a simple fact of life that explains why it is not unusual or unexpected for people to see the same events in significantly different ways and, furthermore, why we tend to see that which aligns with our pre-existing views and dismiss those which challenges them.

While the tendency toward confirming our deeper biases may help us appreciate why different people see the same “evidence” differently, it also raises some serious questions: If our diverse past experiences lead us to see our subjective viewpoints as truth, then how can we know the ultimate reality of anything? Indeed, is there, in fact, any truth that can be known independent of one’s personal perspective? Or is reality just a matter of individual perspective, a reflection always of one’s own “truth” and unique experiences, so to speak? And, if so, are we doomed to disagreement because our perspectives are always and only our own, never truly shared or having any common ground upon which mutual understanding and agreement might happen?

Truth and relativity

Influential linguist John Gumperz observed this paradoxical problem of perspective versus reality in his research on intercultural communication. An anecdote often used to illustrate his discoveries comes from the seemingly innocuous activity of serving gravy. While in a cafeteria at London’s Heathrow airport, Gumperz witnessed a conflict that arose between servers from India and customers from Britain. Although both spoke English, their intonational patterns differed in slight but important ways. Specifically, when offering something to another, British speakers of English use a rising intonation: “Gravy?” In contrast, when Indian speakers of English do the same thing, they do so with a falling intonation: “Gravy.” Though both utterances are intended to achieve the same end, British customers heard the Indian servers not as making a polite offer (“Would you like this gravy?”) but as issuing a curt statement (“This is gravy.”). This subtle difference in intonation led to major misunderstandings between the two parties, with customers complaining that the servers were rude and the servers responding that the customers’ complaints were discriminatory.

In this case, both parties in the discussion left the exchange with clear evidence drawn from their own personal experience that supported their interpretation of the event. However, neither the servers nor the customers saw their evidence as only an interpretation. Rather, because their evidence was their own experience, they took their interpretation of the interaction to be an incontrovertible fact. The predictable result was that the two groups ended up talking past one another, suspicious not only of the other person’s motive but even their sanity.

Now, to be sure, both experiences happened and were, in that sense, real. Moreover, the way in which each person understood their experience, and the way they were impacted by it, was quite real to them. Yet, we encounter a problem when personal experiences are used as the primary, or sometimes even the exclusive, basis for making general conclusions about institutions, cultures, and society. Is it true, is it reality, to say that Indian servers have a culture that is (objectively) rude or that the British customers engage in behaviors that nurture a society that is (systemically) discriminatory and unjust? Without more and varied evidence to provide context beyond personal anecdotes, it seems impossible to answer such questions, as real, important, and relevant as individual experiences may be. Nonetheless, these sorts of big-blanket, general claims are made all the time.

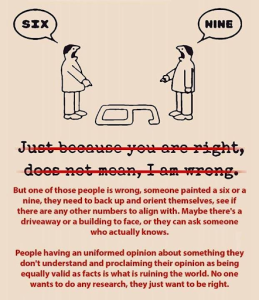

There was a meme that circulated the internet a few years ago that attempted to illustrate a similar point to the one we are making here.

In this illustration, two people come across a number painted on the ground. Standing at opposing ends, one of them sees the number “6” while the other sees a “9.” What they are seeing depends on their specific perspective and, much like the gravy example, both have clear and compelling evidence drawn from their own personal experience that supports their point of view. They both see the number as it is right in front of their very eyes, so they conclude that what they see must be the truth.

But who is right?

The challenge of determining what really is the case, and doing so in the face of compelling personal experience, is not a new problem, as can be seen in many of the polarized and increasingly hostile debates that rage across social media. Indeed, many well-meaning individuals do recognize this. Then, unable to determine whose perspective is the right one but recognizing that each experience represents someone’s reality and wanting to validate those experiences, they give up on the discovery of actual truth as a worthy pursuit. Instead, they fall into a concerning trend toward a form of relativity, speaking of “my truth” and “your truth” as descriptors of what ought to be objective reality.

Personal experience and truth

Of course, if truth is seen in this radically individualized and relativistic way, then we potentially have a simple resolution to the inconsistency in the way different individuals view depictions of the Church in the media: Namely, “both are right.”

From this vantage point, those who see reports as accurate representations of the oppressive Church they experienced are right; it’s “their truth.” And at the same time, those who see the same reports as woefully inaccurate depictions of a fundamentally good and loving Church are also right because that’s “their truth.” Further, because both perspectives are based only on individual experience, neither perspective is open to any serious critical analysis. After all, how do you question someone’s personal experience, especially when the only principle criterion for establishing truth is one’s personal experience?

Yet, somehow the conclusion that both are right seems unsatisfying and wrong. We would agree. It is all a bit too reminiscent of the Dodo bird’s decision regarding the chaotic race described in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: “EVERYBODY has won, and all must have prizes!”

The problem with truth as personal lived experience comes when the broader meaning we apply to our individual experiences—that is, “your truth” and “my truth”—is used to justify general claims about what really is or must be true for all of us.

Returning to the gravy example, we can all probably agree that the following statements are true:

- The servers intended to offer gravy politely. (The “servers’ lived experience”)

- The customers heard the indented offer as a curt statement. (The “customers’ lived experience”)

Disagreement about what is true, however, is more likely to arise when the following interpretations of the above facts are offered:

- British customers are discriminatory. (The “servers’ truth”)

- Indian servers are rude. (The “customers’ truth”)

As we argued above, this latter set of interpretive claims is most problematic when individuals use them to justify how they characterize larger institutions and cultures, such as claiming British society is systemically oppressive or Indian culture is inherently inconsiderate. Whether such conclusions are true or not, they cannot be justified by the evidence presented. Yet, many do just that.

One significant challenge stems, perhaps, from the temptation to ascribe the same sense of objectivity to the meaning we attach to personal experience as we do to the experience itself. The intonational patterns of servers and customers, as well as their intent in offering and receiving gravy, are real and verifiable. However, precisely because different individuals have different experiences, and those different experiences have different meanings for them, one experience alone cannot provide us with a whole picture. Therefore, when reality is filtered only through the lens of one’s individual lived experience, the result is not a reliable or objective conclusion with rationally persuasive power but rather is only a subjective report, a mere interpretation, lacking context and limited to one bit of information.

It seems that perhaps to address this very issue, at least one internet user grew frustrated with the “6 or 9” meme and opted to update it:

In this rendition of the meme, the author is pointing out that although both individuals see the same configuration of paint on the ground, because they see it from different, inherently limited vantage points, they need a broader perspective or better reference point to come to a fuller, more adequate understanding of what the truth of the matter really is.

Or, as Gumperz might say, we need more context.

Broadening our perspectives

Gaining more context suggests a widening of our view and orienting ourselves to a reference point that can help us find what is true by acting as an anchor in a sea of relativism. There are many ways to find more context and probe deeper into narratives as presented. Here, we offer just a few ideas. Is reality just a matter of individual perspective, a reflection always of one’s own “truth” and unique experiences?

While there are many questions that might be asked, and every situation will have its own variables, a few generic questions to use as a starting point might include:

- How did I reach this conclusion?

- What other possible ways might I legitimately interpret this experience?

- If someone else has a conflicting interpretation, why?

- What other sides are there to this argument?

- What assumptions am I making that shape the way I see the descriptive facts of the experience?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of my own argument?

- How can I get more information?

Presume that truth exists. We hold that it is possible to get at the reality of a situation, however contradictory or confusing the evidence may seem at first glance. Of course, finding reality is a complex, nuanced, difficult, and even messy process. It may not always be possible to get the answer to a question quickly or in a satisfactory timeline. Complex issues resist simplistic solutions, and human reality is a very complex business. Nevertheless, if we begin with the assumption that there is an answer, that finding truth is indeed possible despite some challenges, we are likely also to work to discover better ways to find it. It is okay—indeed, it is often wise—to allow things to appear contradictory or even irreconcilable while working toward gaining more information or insight. Rushing to a conclusion can lead to careless reasoning and can get in the way of finding the additional information that is needed. Presuming that there is, indeed, a truth of the matter to be found helps ensure our efforts stay focused on finding it. It helps us to resist succumbing to the temptation to justify pre-existing beliefs or feelings as an easy default that requires little real effort.

Seek further information. When presented with an individual experience, whether your own or that of someone else, it can be tempting to take such experience as definitive, especially in our current world where feelings and personal experiences are so often taken to be unarguable sources of truth. (This is, by the way, a product of what is known as Expressive Individualism. You can read more about it here, here, and here.) Even while we might recognize that different experiences and perspectives are possible, actively seeking them out requires more effort and discipline. Regardless, it is critical to seeing and understanding experiences, both our own and those of others, in their fullest context. Just as larger sample sizes produce better data for the statistician, we should also seek to hear as many experiences as possible lest we reach hasty conclusions based on single data points or on a skewed or misleading selection of “evidence.” This broader approach to understanding does not, however, invalidate any given individual’s experience. Each experience is real and meaningful in its own right. Rather, the approach we are commending here is one that helps us to find more clarity when using those experiences as a basis for making conclusions about a larger institution, culture, or social system.

Engage in civil discourse. Different perspectives are beneficial and worth serious consideration, whether they ultimately turn out to be correct or not. Other viewpoints offer additional context that we might not notice ourselves. This is not to say that we should treat all perspectives as providing equal access to the truth, but rather only that other perspectives provide us with the opportunity to broaden our view such that we may notice nuances or ways to interpret a given event or experience that would otherwise not be available to us. To do this, however, requires that we be willing to engage others in civil discourse. Rarely has anyone ever been persuaded by a feisty meme or mic-drop zinger. That sort of commentary is rather aimed at an audience of those who already share one’s perspective. Sadly, it increasingly pervades the public square, often crowding out more reasonable, thoughtful, and productive forms of discourse. A better way is to engage with others while maintaining an attitude that is both convicted and persuadable. Defending your beliefs while genuinely listening to others is a powerful way to broaden your own perspective, find more context, and increase understanding for both yourself and others. Truly civil discourse is discourse characterized by both passionate belief and intellectual humility; it is discourse more concerned with coming to truthful mutual understanding than with scoring points in a debate of sound-bites or making sure that your opponent knows it is people like you who are going to be on the right side of history.

Finding the right narrative

Lived experience is a powerful and primary way in which we engage and navigate the world, including our association with institutions, cultures, other people, and social systems. It is in and through such things that we discover and shape our views, beliefs, and even those ideas and values we hold to be true. As we have said, the events that any one individual experiences are real. However, because we all filter our views of reality through those very experiences, we must be careful when using them as the basis for making broad conclusions about institutions that are, by nature, composed of many individuals with just as many different lived experiences.

Do recent news and media reports about the Church reflect the actual truth of the matter? There is no denying that the many events they describe happened and are heartbreakingly real. Those who have suffered due to abuse are absolutely justified in their feelings of anger, hurt, and abandonment, especially when those in positions of trust and authority have failed to do enough to stop the abuse. These stories deserve to be told and to be heard, and we must use them to recommit ourselves to ensuring such things happen as infrequently as possible—indeed, to eliminate them entirely. These experiences are real.

That said, however, we need to ask ourselves whether the Church is, in fact, responsible for such abuse or is, to the contrary, an active force in reducing it. To answer this question requires more information to help interpret the experiences of the many individuals that comprise the Church’s membership. This is an ongoing effort to which many have already contributed much additional, needed context. As much of this information makes clear, the Church, on the whole, seems to reduce incidents of abuse overall and is continuing to focus on ways both the institution itself and its members individually can improve in that regard. It is thus critical that we consider all of this context when making conclusions about the institution, lest we weaken the very systems that are making real progress in solving real problems.

More fundamentally, we must be careful not to embrace the narratives provided by others without doing due diligence ourselves. The work of finding truth requires that we listen to and understand personal experiences, but it also demands that we be cautious in drawing conclusions about broader systems based solely on those experiences. This is, to be sure, difficult work, but is vital if we are to find common ground in our mutual efforts to improve individual lives and the institutions that influence them.

The post Is Personal Experience the Final Arbiter of Truth? appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →