The Know

As Nephi planned and prepared to build a ship, his brothers mocked him, saying he was a fool for thinking he could “build a ship … [and] cross these great waters” (1 Nephi 17:17). In response, Nephi reminded his brothers of several of the miracles the Lord performed during Israel’s Exodus from Egypt (see 1 Nephi 17:23–42), including the sending of “fiery flying serpents among them” and then, after they repented, providing the means by which “they might be healed” (1 Nephi 17:41). Modern readers may not readily appreciate how relevant this story was to Lehi and his family’s own circumstances at the time.

The Israelites’ encounter with the “fiery serpents” occurred in the region around the Gulf of Aqaba, a branch of the Red Sea (Number 21:4–9).1 Isaiah later characterized the “fiery flying serpent” as one of “the beasts of the south,” with “south” (negev in Hebrew) referring to the desert region of southern Judah (Isaiah 30:6).2

Biblical texts are not the only sources to describe this as a region infested with flying serpents. An account of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon (ca. 680–669 BC) describes traveling past “yellow snakes spreading wings” in this same region.3 The Greek historian Herodotus (ca. 484–425 BC) also reported hearing stories about “winged serpents” living in the Sinai/Arabian desert and even claimed to have seen the skeletal remains of some.4

All of these sources indicate that the desert regions to the south of Jerusalem were the primary habitat of fiery and/or flying serpents.5 This is the same region Lehi and his family passed through as they fled from Jerusalem, going down to the “borders near the shore of the Red Sea” and setting up a long-term camp along the shores of the Gulf of Aqaba (1 Nephi 2:6).6

Nephi and his brothers then traveled back through this region multiple times as they twice journeyed to and from Jerusalem (1 Nephi 3–5, 7). The family remained encamped near this area, at a site they designated the Valley of Lemuel, until the Lord commanded Lehi to leave (1 Nephi 16:9–11). Thus, as Neal Rappleye observed, “the bulk of the narrative in 1 Nephi takes place in this region between Jerusalem and the Red Sea, in the midst of the traditional habitat associated with the winged seraph-serpents.”7

Based on the details in biblical, historical, and archaeological sources, Israeli biblical scholar Nissim Amzallag argued that the “fiery flying serpent” should be identified with the saw-scaled viper (Echis coloratus), a venomous snake whose habitat includes most of western Arabia still today.8 If this correlation is correct, then Lehi and his family likely would have continued to encounter “fiery flying serpents” (the saw-scaled viper) even as they journeyed farther south into the Arabian wilderness.9

Nephi referenced the fiery flying serpents while the family was staying in Bountiful (1 Nephi 17:41), which was most likely located in the frankincense-producing region of Dhofar in Oman.10 According to Herodotus, in this area “great numbers of winged serpents … carefully guard each [frankincense] tree.”11 Other classical Greek sources also mention these snakes.12 Based on the details in these accounts, Amzallag has argued that these are also referring to the saw-scaled viper, which is known to live in both Yemen and the Dhofar.13

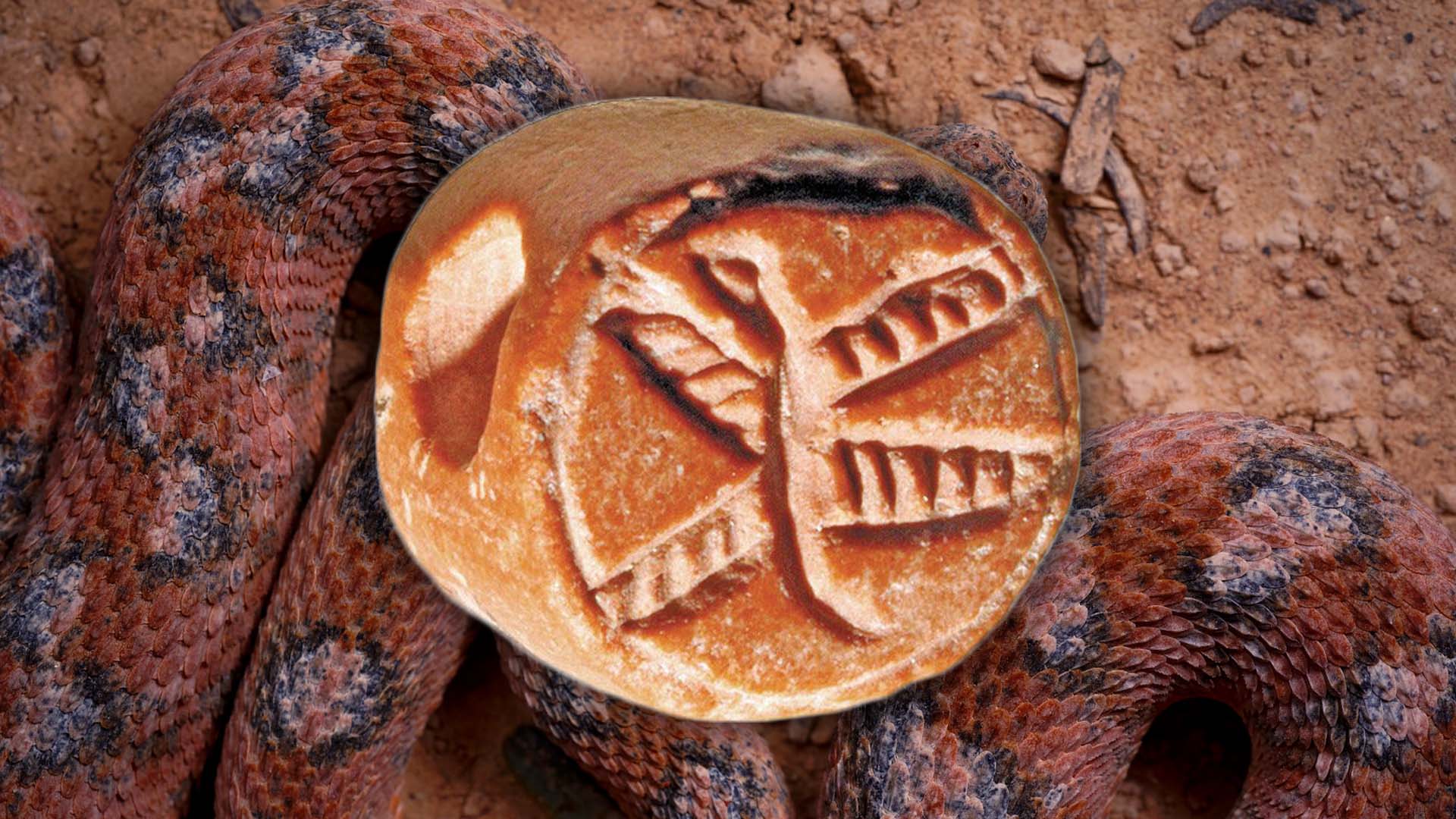

The South Arabian cultures that controlled the frankincense trade had serpent-related symbols and traditions similar to those found in Israel, including the production of bronze snake artifacts reminiscent of Moses’s brazen serpent.14 Thus, while in Bountiful Lehi’s family was still within the habitat of—and among cultures influenced by—the fiery flying serpents.

The Why

Scholars have long noted the presence of Exodus motifs throughout Nephi’s account of his family’s wilderness journey.15 Recognizing how the environment they traveled through overlapped with and was similar to that of the Israelite Exodus—including the same wildlife, such as the saw-scaled viper—brings to life how palpably like the Exodus the family’s journey must have seemed to the group of Israelite travelers. They faced the same dangers and similarly had to rely on the Lord for their protection. This is especially evident when considering the story of the fiery (flying) serpents.16

As several scholars have previously noted, in Numbers 21:4–9, the fiery serpents act as agents of the Lord, sent by Him to afflict Israel and bring them to repentance.17 According to some scholars, the nuances of the Hebrew imply that the serpents were released or let go by the Lord, thereby implying they were an ever-present danger that the Lord held at bay to protect Israel but were released due to Israel’s disobedience.18

As ancient Israelites, Lehi and his family would have shared this belief that the fiery flying serpents that they encountered on their journey were agents of the Lord. This made Nephi’s reference to that story an especially potent reminder of the real dangers the family could face if they did not heed the Lord’s counsel. As Rappleye has noted:

When Nephi reminded his brothers of the “flying fiery serpents” sent by the Lord to chastise the children of Israel for their murmuring (1 Nephi 17:41), it would have held a relevance that is often lost on readers today: they, too, were traveling and camping in the regions believed to be infested by flying serpents, and if they were not faithful, the Lord could just as easily punish them by unleashing those dangerous snakes.19

Yet this also came with a reminder of the Lord’s grace: just as the Lord had “prepared a way that [the Israelites] might be healed” by looking upon the brazen serpent (1 Nephi 17:41; see Numbers 21:6–9), so too could Laman and Lemuel and the rest of Lehi’s family be healed and protected if they would only repent and look to the Lord (see Alma 33:19–22; 37:38–47). This same blessing of healing and protection through Jesus Christ’s Atonement remains available to all today who look to the Lord and follow Him.

Further Reading

Neal Rappleye, “Serpents of Fire and Brass: A Contextual Study of the Brazen Serpent Tradition in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 50 (2022): 217–298.

S. Kent Brown, “Fiery Flying Serpents,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003), 270.

Terrence L. Szink, “Nephi and the Exodus,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 38–91.

- 1. See Anson F. Rainey and R. Steven Notley, The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Jerusalem, Israel: Carta, 2006), 121.

- 2. See Joel F. Drinkard Jr., “Negev,” in HarperCollins Bible Dictionary, rev. ed., ed. Mark Allan Powell (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2011), 694–695; Lynn Tatum, “Negeb,” in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, ed. David Noel Freedman (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000), 955.

- 3. Translation in Karen Radner, “Esarhaddon’s Expedition from Palestine to Egypt in 671 BCE: A Trek through Negev and Sinai,” in Fundstellen: Gesammelte Schriften zur Archäologie und Geschichte Altvorderasiens ad honorem Hartmut Kühne, ed. Dominik Bonatz, Rainer M. Czichon, and F. Janoscha Kreppner (Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz, 2008), 307, rev. lines 5–7.

- 4. Robert B. Strassler, ed., The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories, trans. Andrea L. Purvis (New York, NY: Anchor Books, 2007), 151.

- 5. See Robert Rollinger, “Herodot (II 75f, III 107–109), Asarhaddon, Jesaja und die fliegenden Schlangen Arabiens,” in Ad Fontes! Festschrift für Gerhard Dobesch zum fünfundsechzigsten Geburtstag am 15. September 2004, ed. Herbert Heftner and Kurt Tomaschitz (Vienna, Austria: Vienna Humanistic Society, 2004), 927–944.

- 6. On Lehi’s route from Jerusalem and the location of the Valley of Lemuel, see Warren P. Aston, “Into Arabia: Lehi and Sariah’s Escape from Jerusalem,” BYU Studies Quarterly 58, no. 4 (2019): 99–126. See also S. Kent Brown, “Jerusalem Connections to Arabia,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 626–629; George D. Potter, “A New Candidate in Arabia for the Valley of Lemuel,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 8, no. 1 (1999): 54–63.

- 7. Neal Rappleye, “Serpents of Fire and Brass: A Contextual Study of the Brazen Serpent Tradition in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 50 (2022): 225. The term seraph used by Rappleye is the Hebrew word used for “fiery serpent” (pp. 219–220).

- 8. Nissim Amzallag, “The Origin and Evolution of the Saraph Symbol,” Antiguo Oriente 13 (2015): 99–126. Alternatively, Philippe Provençal, “Regarding the Noun שרף in the Hebrew Bible,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 29, no. 3 (2005): 371–379, has argued that it should be identified with the red spitting cobra (Naja pallida), which is only known to inhabit the northern part of Arabia but may have inhabited the region further to the south in antiquity. Richard Lederman, “What Is the Biblical Flying Serpent?,” TheTorah.com, January 1, 2015, argued, “Saraph is likely not a specific species, but refers to cobras in general,” including the Egyptian cobra (Naja haje) and Arabian cobra (Naja arabica), both of which are known to inhabit regions throughout the Arabian Peninsula including Yemen and the Dhofar (in southwestern Oman).

- 9. See Rappleye, “Serpents of Fire and Brass,” 224–227, which documents additional connections to the brazen/fiery serpent narrative and Lehi’s journey.

- 10. For the two main proposals on the location of Bountiful—both within the Dhofar region—see Warren P. Aston, “The Arabian Bountiful Discovered? Evidence for Nephi’s Bountiful,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 7, no. 1 (1998): 4–11, 70; George D. Potter, “Khor Rori: A Maritime Resources-Based Candidate for Nephi’s Harbor,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 51 (2022): 253–294. For an overview of each location, see Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Bountiful,” Evidence #0164, March 9, 2021, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 11. Strassler, Landmark Herodotus, 258–259.

- 12. See Nigel Groom, Frankincense and Myrrh: A Study of the Arabian Frankincense Trade (Harlow, UK: Longman, 1981), 59–60, 66, 70, 242n9.

- 13. Amzallag, “Origin and Evolution,” 107.

- 14. See, for example, the bronze snake found at al-Ḥadāʾ and dated to the early first millennium BC in Alessia Prioletta, Inscriptions form the Southern Highlands of Yemen (Rome, Italy: L’erma di Bretschneider, 2013), 303–304. For more information on the serpent symbolism and artifacts from Yemen and Oman, see Tracey Cian, “Snake Cults in Iron Age Southeastern Arabia: A Consideration on Autochthonous Developments and Possible Connections with Middle Eastern Traditions” (master’s thesis, University College London Qatar, 2015), 46–87.

- 15. See Terrence L. Szink, “Nephi and the Exodus,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 38–91; Mark J. Johnson, “The Exodus of Lehi Revisited,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 3, no. 2 (1994): 123–126; Don Bradley, “A Passover Setting for Lehi’s Exodus,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 34 (2020): 119–142. Rappleye, “Serpents of Fire and Brass,” 249n2, cites additional studies.

- 16. On the equivalency of the “fiery serpents” and the “fiery flying serpents,” see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Nephi Say Serpents Could Fly? (1 Nephi 17:41),” KnoWhy 316 (May 22, 2017).

- 17. On snakes as agents of the Lord in Numbers 21 and other biblical and ancient Near Eastern contexts, see Rappleye, “Serpents of Fire and Brass,” 237–238.

- 18. See Amy Birkan, “The Bronze Serpent, a Perplexing Remedy: An Analysis of Numbers 21:4–9 in the Light of Near Eastern Serpent Emblems, Archaeology and Inner Biblical Exegesis” (master’s thesis, McGill University, 2005), 65–67. Douglas W. Ullmann, “Moses’s Bronze Serpent (Numbers 21:4–9) in Early Jewish and Christian Exegesis” (PhD diss., Dallas Theological Seminary, 1995), 29–30, argues against this interpretation, however.

- 19. Rappleye, “Serpents of Fire and Brass,” 226–227, capitalization silently altered.

Continue reading at the original source →