The Know

When Lehi and his family arrived in the promised land, according to Nephi’s account, they found “beasts in the forests of every kind, … the ass and the horse, … and all manner of wild animals” (1 Nephi 18:25). The inclusion of horses in the Book of Mormon is a subject that has long perplexed many readers since conventional thinking among scientists maintains that horses went extinct in the Americas around the end of the last Ice Age (ca. 10,000 BC). Some have used this apparent discrepancy to try to discredit the Book of Mormon. Others, however, have argued that various possibilities could account for it.1

For example, some have suggested that the use of the term “horse” is an instance of what scholars call “loanshifting” or “referential extension,” where a familiar word is applied to a foreign item or concept.2 This has happened frequently when new cultures encountered the horse in both the Old and New Worlds.3 Some scholars suggest something similar may have happened when Lehi’s family first explored the promised land—that is, they may have extended their term for “horse” to a new, unfamiliar species.4 Others have noted that translation sometimes introduces anachronisms into a text and so propose that words like “horse” may be a result of the Book of Mormon’s translation into English.5

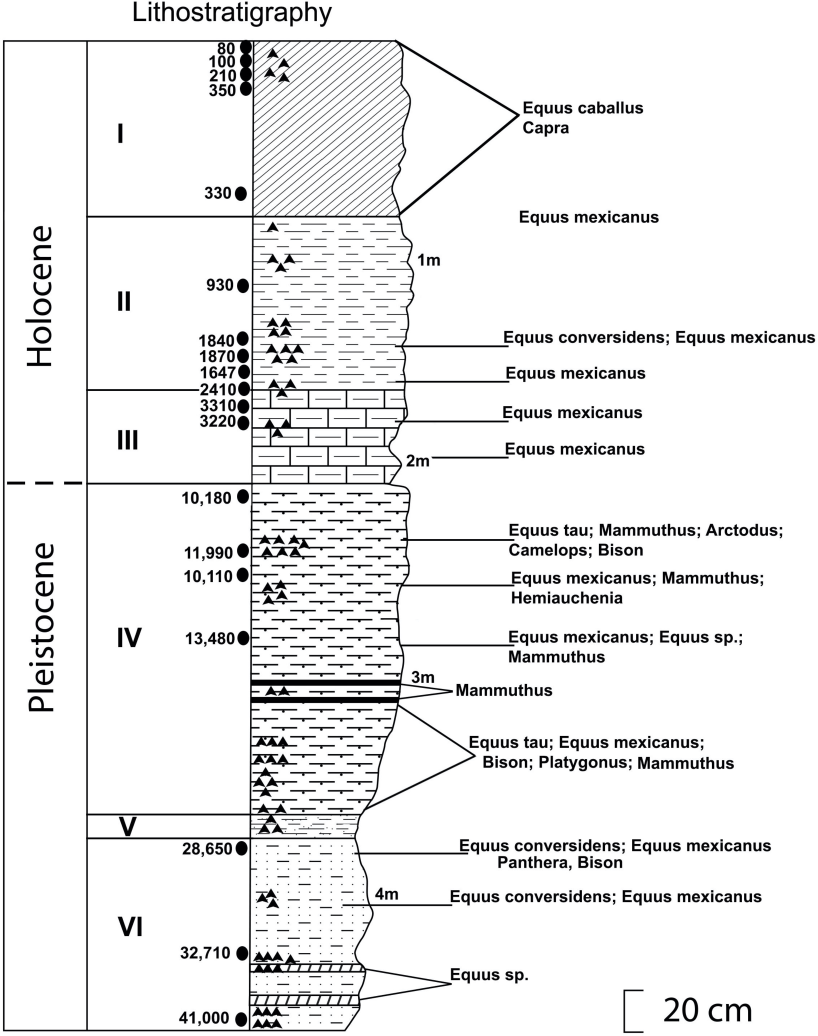

While these remain important possibilities to consider, a recent study published in the Texas Journal of Science indicates that horses may have been in the Americas during Book of Mormon times after all.6 An international team of scholars—including experts in geology, biology, paleontology, and archaeozoology—recovered specimens of horse and other megafauna from a stratified context at Rancho Carabanchel, near Cedral, San Luis Potosí, Mexico. To establish the chronology of the site, several radiocarbon dates were obtained at each layer of strata from charcoal and other organic material recovered during excavations. Importantly, several horse specimens were recovered in close association with materials carbon dated to Book of Mormon times (see table).7

|

Post-Pleistocene, Pre-Columbian Dates Associated with Horse Remains at Rancho Carabanchel, San Luis Potosí, Mexico (see Miller et al. 2022, table 1) |

|||

|

Uncalibrated Radiocarbon Dates |

Calibrated Radiocarbon Dates |

||

|

Years BP* |

Years in BC/AD |

Years BP* |

Years in BC/AD |

|

3310±30 |

1390–1330 BC |

3610–3458 |

1660–1508 BC |

|

3220±30 |

1300–1240 BC |

3494–3374 |

1544–1424 BC |

|

2410±30 |

490–430 BC |

2498–2350 |

548–400 BC |

|

1870±30 |

50–110 AD |

1877–1724 |

73–226 AD |

|

1840±30 |

80–140 AD |

1864–1708 |

86–242 AD |

|

1647±57 |

247–360 AD |

1697–1408 |

253–542 AD |

|

930±30 |

990–1050 AD |

925–785 |

1025–1165 AD |

|

*BP = “before present,” with the “present” standardized to 1950. |

|||

Based on the researchers’ analysis of the recovered horse specimens, all the samples from pre-Columbian, post-Pleistocene (Ice Age) contexts belong to either Equus mexicanus or Equus conversidens, both now extinct North American horse species. This rules out the possibility that these were actually Spanish horse bones that somehow contaminated the lower strata of the site.

The authors of the study concluded: “The remains of Equus that we recovered from RC [Rancho Carabanchel] from multiple stratigraphic layers all with associated radiocarbon dates, all in a fair stratigraphic continuum (Fig. 3), and showing no mixing between geological units imply that horses may have persisted in this region of México well after the classical late Pleistocene extinction time.”8

Although this is incongruous with the commonly assumed date for the extinction of the horse in America, it is consistent with the traditions of several Indigenous groups which insist that their people had horses before the Spanish arrived.9 It is also part of a growing body of evidence that suggests that at least some pockets of horses survived for several millennia after the end of the last Ice Age.10 For instance, studies of ancient DNA samples from Alaska and the Yukon found horse DNA in permafrost layers from between 8600–5700 BC and 3700 BC, respectively.11 Further south, some horses in Brazil and Argentina apparently survived as late as 5000 BC.12

In Mesoamerica, scholars have long been perplexed by horse bones found in conjunction with ceramics in northern Yucatan.13 Charcoal found in association with some of these horse specimens was radiocarbon dated to ca. 1840 BC, and additional horse remains were found in later pre-Columbian strata.14 In the past, scholars have raised questions about the stratigraphy of the site, but recently one pair of archaeologists concluded that the possibility that the horse “survived into the Late Archaic or even Early Preclassic” should be taken more seriously: “Since the horse also survived into post-Pleistocene times in the Old World, the possibility of its survival into Archaic times in the American tropics may also need to be considered.”15 The most recent findings reported from Mexico further reinforce that possibility.

The Why

Establishing the survival of horse populations in the Americas well beyond the last Ice Age has major implications that would reverberate across several disciplines engaged in the study of pre-Columbian American history, “creating a paradigm shift,” as the authors of this latest study have acknowledged.16 Whether this latest evidence will bring about such a shift is yet to be seen, but the scientists who published it have urged others to treat the possibility “as a developing hypothesis, which is testable rather than just avoided.”17

Although the issue is not yet definitively settled, the potential implications of these latest findings on how we read and interpret references to horses and other animals in the Book of Mormon are very much worth considering. In this light, it is particularly interesting to compare these latest findings to the dating of various Book of Mormon references to horses.

Two of the radiocarbon dates found near horse remains came from the mid-second millennium BC, thereby supporting the reference to horses during Jaredite times in Ether 9:19.18 Another dates to the sixth or fifth century BC, which is chronologically close to Lehi’s arrival in the promised land, when Nephi said he saw horses there (1 Nephi 18:25), and to Enos’ time when the Nephites had “many horses” (Enos 1:21). The final mention of horses in the Book of Mormon comes during the Gadianton siege in the first century AD (3 Nephi 3:22; 4:4; 6:1), and two radiocarbon dates support the presence of horses around this time as well. Thus, if these findings are valid, they support the existence of horses in all periods the Book of Mormon mentions them in.19

Additionally, it may be significant that two different types of Equus species were found in strata dating to Book of Mormon times since the Book of Mormon also mentions the ass (donkey), which is likewise a member of the so-called horse family (Equidae). Since the E. coversidens is a small- to medium-sized horse, perhaps it is what the Jaredites and Nephites referred to as an ass,20 while the larger E. mexicanus was their horse. The findings at Rancho Carabanchel may therefore help account for not one, but two animals mentioned in the Book of Mormon.

As scientists and scholars continue to explore and debate this issue, students of the Book of Mormon should remain open to various explanations for references to horses and other Old World animals mentioned in Jaredite and Nephite records. These recent findings once again illustrate why it is important to remain patient and open-minded as archaeology continues to unfold the past rather than jump to hasty conclusions based on a mere lack of evidence. The potential discovery of pre-Columbian horses during Book of Mormon times is but a single data point in a much larger trend toward confirming things once thought to be anachronous in the Book of Mormon.21

“In scholarship as in science,” Hugh Nibley once observed, “every paradox and anomaly is really a broad hint that new knowledge is awaiting us if we will only go after it.”22 Those who have had the patience to approach the Book of Mormon’s reference to horses as just such a broad hint are now enjoying new knowledge that may be on the verge of rewriting the history of the Americas.

Further Reading

Wade Miller et al., “Post-Pleistocene Horses (Equus) from México,” Texas Journal of Science 74, no. 1 (2022): article 5.

Wade E. Miller and Matthew Roper, “Animals in the Book of Mormon,: Challenges and Perspectives,” BYU Studies Quarterly 56, no. 4 (2017): 159–165.

Daniel Johnson, “‘Hard’ Evidence of Ancient American Horses,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54 (2015): 149–179.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Are Horses Mentioned in the Book of Mormon? (Enos 1:21),” KnoWhy 75 (April 11, 2016).

- 2. Lawrence B. Kiddle, “Spanish and Portuguese Cattle Terms in Amerindian Languages,” in Italic and Romance Linguistics Studies in Honor of Ernst Pulgram, ed. Herbert J. Izzo (Amsterdam, NE: John Benjamin’s Publishing, 1980), 273, 285, defines loanshifting as “[giving] the animal the name of a familiar animal which the receiving speakers believe it resembles” and “[involving] a familiar animal whose name is applied to the acculturated foreign animal.” Cecil H. Brown, Lexical Acculturation in Native American Languages (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999), 25, 28, defines loanshift differently but uses the term referential extension for “extending referential use of a word for some familiar object or concept to a somewhat similar introduced object or concept.”

- 3. See Orly Goldwasser, “What Is a Horse? Lexical Acculturation and Classification in Egyptian, Sumerian, and Nahuatl,” in Classification from Antiquity to Modern Times: Sources, Methods, and Theories from an Interdisciplinary Perspective, ed. Tanja Pommerening and Walter Bisang (Boston, MA: De Gruyter, 2017), 45–65.

- 4. This is one of several possibilities discussed in John L. Sorenson, An American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1985), 288–299, esp. 295–296; John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 313–319.

- 5. Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 289–300; Brant A. Gardner, “Anachronisms in the Book of Mormon,” in A Reason for Faith: Navigating LDS Doctrine and Church History, ed. Laura Harris Hales (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2016), 33–43.

- 6. Wade Miller et al., “Post-Pleistocene Horses (Equus) from México,” Texas Journal of Science 74, no. 1 (2022): article 5. This research was previously presented at the 2021 conference of the Geological Society of America. See Wade Miller et al., “Post-Pleistocene, Pre-Columbian Horses from a Site in San Luis Potosi, Mexico,” Geological Society of America Abstracts and Programs 53, no. 6 (2021).

- 7. Unfortunately, researchers were not able to obtain any carbon dates directly from the pre-Columbian horse bones themselves because insufficient collagen had survived. This is a common challenge when dealing with ancient animal remains. See Terry O’Connor, The Archaeology of Animal Bones (Thrupp, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2000), 23–24.

- 8. Miller et al., “Post-Pleistocene Horses.”

- 9. See Yvette Running Horse Collin, “The Relationship Between the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas and the Horse: Deconstructing a Eurocentric Myth” (PhD diss., University of Alaska—Fairbanks, 2017), 73–101.

- 10. Much of this evidence is summarized in Wade E. Miller, Science and the Book of Mormon: Cureloms, Cumoms, Horses & More (Laguna Niguel, California: KCT & Associates, 2010), 76–83; Daniel Johnson, “‘Hard’ Evidence of Ancient American Horses,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54 (2015): 149–179; Wade E. Miller and Matthew Roper, “Animals in the Book of Mormon: Challenges and Perspectives,” BYU Studies Quarterly 56, no. 4 (2017): 159–165. Although older and not entirely up-to-date, John L. Sorenson, “Animals in the Book of Mormon: An Annotated Bibliography,” FARMS Report (1992), is also still useful.

- 11. James Haile et al., “Ancient DNA Reveals Late Survival of Mammoth and Horse in Interior Alaska,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, no. 52 (2009); Tyler J. Murchie et al., “Collapse of the Mammoth-Steppe in Central Yukon as Revealed by Ancient Environmental DNA,” Nature Communications 12 (2021): article 7120.

- 12. Mario Pichardo, “Review of Horses in Paleoindian Sites of the Americas,” Anthropologischer Anzeiger 62, no. 1 (2004): 28.

- 13. See, for example, Clayton E. Ray, “Pre-Columbian Horses from Yucatan,” Journal of Mammalogy 38, no. 2 (1957): 278. Additional findings are cited in Sorenson, American Setting, 295, 394n63; Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 316–317.

- 14. Anthony P. Andrews and Fernando Robles Castellanos, “The Paleo-American and Archaic Periods in Yucatan,” in Pathways to Complexity: A View from the Maya Lowlands, ed. M. Kathryn Brown and George J. Bey III (Gainsville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2018), 25.

- 15. Andrews and Castellanos, “Paleo-American and Archaic Periods,” 25–26. The Archaic period is defined as 8000–2000 BC (p. 17), with the late Archaic period as 2500–2000 BC and Early Preclassic as 2000–1500 BC (p. 21).

- 16. Miller et al., “Post-Pleistocene Horses.”

- 17. Miller et al., “Post-Pleistocene Horses.”

- 18. The exact chronology of the Jaredites is somewhat indeterminate, but John E. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 2 (2005): 46, dates the reign of Riplakish (Ether 10:4) to ca. 1200 BC. Since horses are mentioned during the reign of Emer (Ether 9:15–21) and Emer was five generations before Riplakish (Ether 1:24–28), a reasonable estimate for the date of his reign would be around 1400 BC, which accords well with the two radiocarbon dates from this period (see table).

- 19. Horses are also mentioned in the story of Ammon and Lamoni, in the first century BC (Alma 18:9–10, 12; 20:6). Although none of the radiocarbon dates specifically tie into that time period, it would logically follow that if there were horses in this region in the sixth–fifth century BC and they were still there in the first–third century AD, horses must have also been living in the same region in the first century BC.

- 20. See 1 Nephi 18:25; Mosiah 5:14; 12:5; Ether 9:19.

- 21. See John E. Clark, “Archaeological Trends and Book of Mormon Origins,” in The Worlds of Joseph Smith: A Bicentennial Congress, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2006), 83–104; Matt Roper and Kirk Magleby, “Time Vindicates the Prophet” (address, 2019 FAIR Conference, August 2019).

- 22. Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1988), 365–366.

Continue reading at the original source →