The Know

During His ministry, Jesus was once approached by some of the leading scribes and Pharisees who would state, “Master, we would see a sign from thee” (Matthew 12:38). Upon their request for a sign, Jesus referred explicitly to the prophet Jonah: “An evil and adulterous generation seeketh after a sign; and there shall no sign be given to it, but the sign of the prophet Jonas: for as Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale’s belly; so shall the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:39–40).

This sign of Jonah has obvious connections to the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. However, these symbols may be strengthened by an early understanding of the book of Jonah that saw symbolism in the reference to the “great fish” (Jonah 1:17) that swallowed the runaway prophet. In many ancient Near Eastern worldviews, a sea serpent or leviathan represented death and hell.1 We may understand that Jonah, by being swallowed by a great fish, died and was then brought back to life. Seen in this way, David R. Scott explained, “The great fish may be a metaphor for the leviathan, the mouth of hell, the great deep, Sheol, and death. By this reasoning, the Lord pulled Jonah back from the watery grave, revived him, and gave him a second chance to obey.”2

The symbolic interpretation of the fish as the monster of death and hell likewise appears in the medieval Zohar, a Jewish mystical work: “The fish that swallowed him is, in fact, the grave; and so ‘Jonah was in the belly of the fish,’ which is identified with ‘the belly of the underworld.’”3 Jonah’s miraculous survival as he washed up on shore was likewise seen as a symbol for the future resurrection of humankind by these medieval commentators. According to Latter-day Saint scholar LeGrande Davies, “Though the Zohar is quite late, the ideas and conceptions in it are important,”4 and it may “be recognized as an authentic tradition carrier from much earlier times.”5

In addition to the overt reference to the sign of Jonah in Matthew 12:39, other indirect references to this prophet appear subtly throughout the New Testament. For instance, Jonah’s name is the Hebrew word for “dove,” which is especially known by Christians as the sign that was manifest at the baptism of Jesus to represent the descending of the Holy Ghost upon Him as He came up out of the waters of baptism.6

A wide array of symbolic meanings was attached to doves in ancient times. One meaning connected doves “with some aspect of the divine.”7 This symbolism is reflected in the Babylonian Talmud, which comments that “‘the spirit of God hovered over the face of the waters” [Genesis 1:2],’ like a dove hovering over its young without touching them.”8The return of the dove with an olive leaf was a sign to Noah that the flood waters of destruction were abating (Genesis 8:11). Doves are also linked to peace and prosperity and were used to carry messages—thus it is only fitting that a member of the Godhead, the Holy Ghost, used the sign of the dove at Jesus’s baptism, acting as a messenger that the true peace giver had arrived.

Doves, as a symbol for the divine, also played an important aspect in Old Testament laws relating to temple sacrifice. Doves were an acceptable animal to sacrifice in the temple,9 and instances of their use in temple settings appear in both the Old and New Testaments (see, for example, Genesis 15:6 and Luke 2:24). Just as the sacrifice of doves foreshadowed and pointed to the “great and last sacrifice” performed by Jesus Christ (Alma 34:14), Jonah, a “dove,” offered himself for sacrifice in an effort to save the lives of the sailors caught in the tempest (see Jonah 1:12).

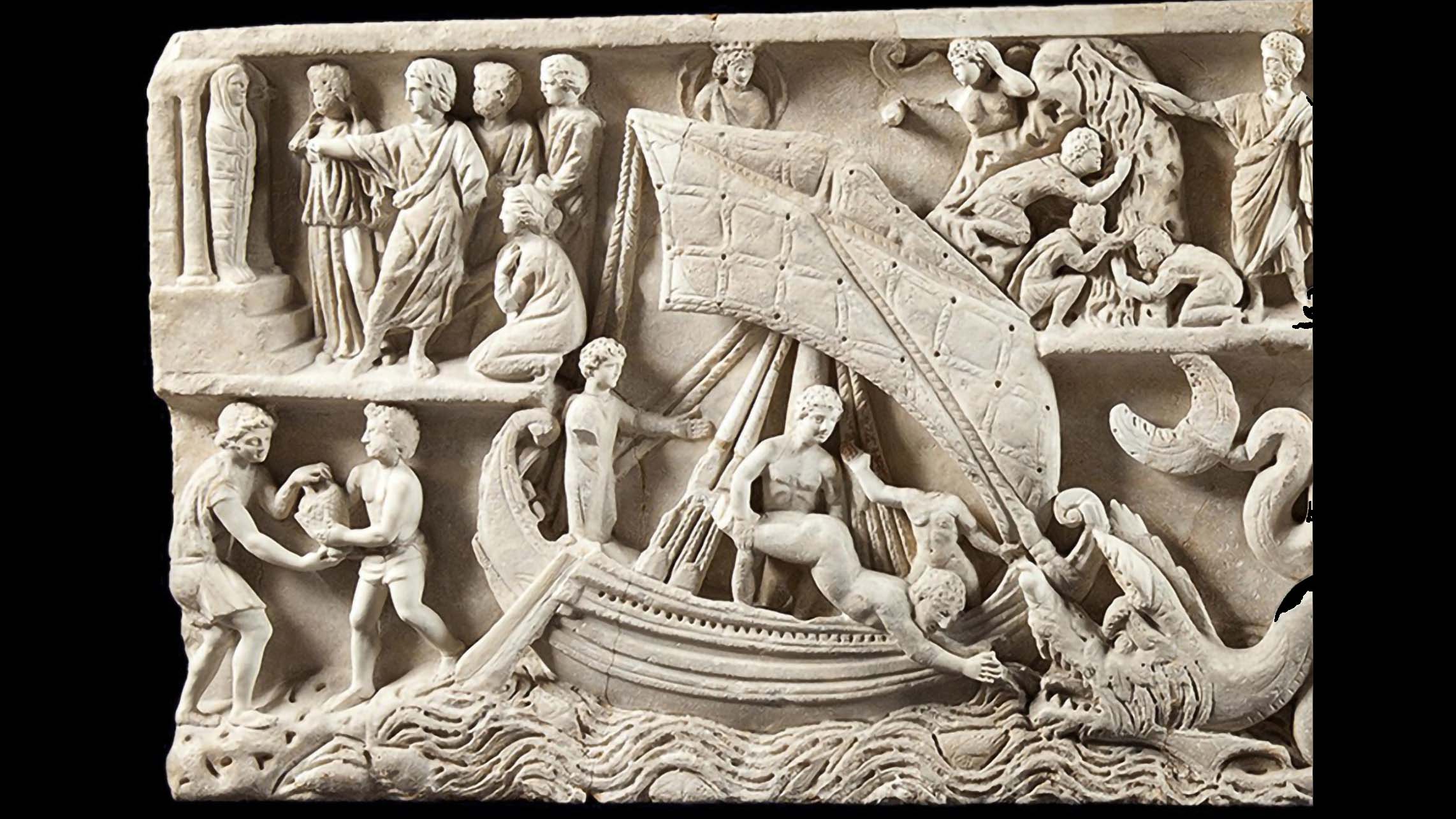

It is apparent that Jonah was important to early Christians as well, who connected his story to death and resurrection in light of Jesus’s “sign of Jonah.” Many of the early Christian tombs that have been found depict events from the life of Jonah, connecting them to various aspects of the ministry and Atonement of Jesus Christ and, by extension, to their own hopes for the Resurrection.10 Furthermore, doves played an important role in Christian identity in the early centuries of the Church before the sign of the cross became dominant.11 Clement of Alexandria, for example, listed various symbols that could be employed by Christians: “And let our seals be either a dove, or a fish, or a ship scudding before the wind … or a ship’s anchor.”12 Significantly, each of these signs is found in the early Christian representations of Jonah’s life.

The Why

David R. Scott stated, “One purpose of the book of Jonah is to preserve an elaborate declaration and coded testimony of who this Messiah is.”13 Specifically, Scott has found that the book of Jonah depicts the runaway prophet as a type of Christ—many aspects of the two prophets’ lives are parallel.

As doves symbolized peace and some aspect of the Godhead, Jonah would be expected to act with the proper desire to establish peace. However, in an ironic twist of the meaning of his name, he is not sent to declare peace to Nineveh but rather destruction. Even after the city of Nineveh repented and averted the punishments of God, Jonah harbored hard feelings for the Assyrians and could not feel joy at the prospect of their repentance (see Jonah 4).

This is in stark contrast with Jesus, who actively sought out sinners and rejoiced in their repentance. Jesus, the Prince of Peace, began his ministry with a sign of peace offered at His baptism. Later, He rose triumphant from the grave, like Jonah being washed ashore after three days and three nights. Jesus’s Resurrection was more powerful, however, and soon Jesus inaugurated the preaching of the gospel of peace to the whole world, of which Jonah’s preaching to Nineveh was a type.

The possibility of a symbolic meaning behind the great fish in Jonah does not negate the historical reality of the prophet. Rather, according to Davies, “This typological interpretation can easily be that of a literal historical prophet who lived his life as an example, testimony, or foreshadowing of the power of the resurrection by the Lord and the regenerative power of repentance.”14 Such a reading, however, can offer additional insights to Jesus’s life, ministry, and Atonement. Just as the Lord taught that “all things are created and made to bear record of [Him]” (Moses 6:63), so too does Jonah’s ministry bear record that Jesus is the Christ, the true giver of eternal peace.15

Further Reading

David R. Scott, “The Book of Jonah: Foreshadowings of Jesus as the Christ,” BYU Studies Quarterly 55 no. 3 (2016): 161–180.

LeGrande Davies, “Jonah: Testimony of the Resurrection,” in Isaiah and the Prophets: Inspired Voices from the Old Testament, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1984), 89–104.

- 1. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does Jacob Choose a “Monster” as a Symbol for Death and Hell? (2 Nephi 9:10),” KnoWhy 34 (February 16, 2016).

- 2. David R. Scott, “The Book of Jonah: Foreshadowings of Jesus as the Christ,” BYU Studies Quarterly 55 no. 3 (2016): 166.

- 3. Harvey Sperling and Maurice Simon, trans., The Zohar, vol. 4 (New York, NY: Rebecca Bennet, 1958), 173–176. As cited by LeGrande Davies, “Jonah: Testimony of the Resurrection,” in Isaiah and the Prophets: Inspired Voices from the Old Testament, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1984), 98. This translation refers to sheol as the underworld, in contrast with the King James translators’ rendition of the word as “hell” in Jonah 2:2. Sheol is the name of the world of spirits in Hebrew thought and does not distinguish between the righteous or the wicked, making “hell” a poor translation when one considers the theological concepts attached to the word.

- 4. Davies, “Jonah: Testimony of the Resurrection,” 98.

- 5. Davies, “Jonah: Testimony of the Resurrection,” 97.

- 6. Matthew 3:16; Mark 1:10; Luke 3:21–22.

- 7. Dorothy Willette, “The Enduring Symbolism of Doves: From Ancient Icon to Biblical Mainstay,” Bible History Daily, Biblical Archaeology Society, July 26, 2022.

- 8. William Davidson, trans., Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Moed, Hagiga 15a:3. This is also reflected in the Aramaic Targum of Song of Songs 2:12, which refers to the dove as “the Holy Spirit of Redemption.”

- 9. See Leviticus 5:7; 12:14; 14:22, 30.

- 10. One such example is found on the ceiling of the Catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus in Rome, Italy. It depicts Jonah being thrown into the sea, praying in the belly of the fish, and being vomited onto dry ground. A fourth depiction from Jonah’s life was originally included but is no longer extant. Four men are depicted praying with uplifted hands beside each depiction, and at the center Jesus is depicted as the Good Shepherd.

- 11. Elder Jeffery R. Holland has recently discussed the origins of the cross in Christian worship in a general conference address. See Jeffrey R. Holland, “Lifted Up upon the Cross,” October 2022 general conference; another treatment of this topic can be found in John Hilton III, Considering the Cross: How Calvary Connects Us with Christ (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2021).

- 12. Clement of Alexandria, Pedagogus 3:11.

- 13. Scott, “Book of Jonah,” 176.

- 14. Davies, “Jonah,” 99.

- 15. See Monte S. Nyman, “The Twelve Prophets Testify of Christ,” in A Witness of Jesus Christ: The 1989 Sperry Symposium on the Old Testament, ed. Richard D. Draper (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990), 209.

Continue reading at the original source →