Gordon Wiseman was attending a conference at BYU when he heard the call to engage with non-believers online. He entered the social media fray, boldly testifying of truth, denouncing what he saw as false doctrine, and weighing in on social issues. He had heated exchanges with non-believers and public disagreements with people he once thought were on his side.

Wiseman, however, began to question the effectiveness of his online missionary work. He was gaining followers but couldn’t shake the feeling that some of his posts were causing more harm than good. He even considered closing his accounts and limiting his proselyting efforts to the physical world. He realized he was coming across as an attack dog for his beliefs when he wanted to be a missionary. Culture warriors cherry-pick individuals and messages that they disagree with.

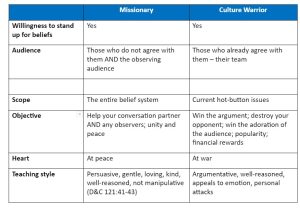

What distinguishes a culture warrior from a missionary?

Culture warriors actively promote and defend their ideology in a combative manner. The Latter-day Saint writer Nathaniel Givens described them as manipulated by “cultural warmongers” who profit from anger and contention. Missionaries, on the other hand, promote their beliefs in a charitable manner under God’s guidance.

The key difference between a culture warrior and a missionary is the audience. Culture warriors do not care about the person they are directly interacting with. They care about the audience observing the interaction. They want the attention and approval of those who already agree with them, making their behavior a bid for popularity.

Sherem, from the Book of Mormon, is an excellent example of an ancient culture warrior. He attempted to lead people away from God towards his own ideology and sought an audience with Jacob to humiliate him and disprove his beliefs publicly. However, Jacob proved him wrong, and Sherem lost all his followers after what appeared to be a divinely inflicted cardiac event. Jacob’s supporters still attempted to nourish Sherem back to health, but he passed away in disgrace.

In contrast, a missionary’s audience is the person he or she is interacting with and, secondarily, anyone who observes the exchange. Missionaries seek to understand and connect with the person in front of them, even when that person treats them as an enemy. And their goal is not to rally those observing but to edify them.

How to identify a culture warrior

It’s easy to detect culture warriors because they cherry-pick individuals and messages that they disagree with. Then they tear them apart in front of an audience. Culture warriors grab short clips or screenshots of the most extreme people and the easiest arguments to ridicule. They may even falsely attribute an idea to someone and then attack them for it.

By choosing the most extreme opponents, their goal is clearly not to change minds but rather to increase enmity between their side and the other. Their opponents often don’t even know they are under attack because it is happening in some hidden corner of the Internet, or the culture warrior takes a screenshot and places it somewhere where only his tribe can react. The culture warrior might even use religious or cultural references that are clearly intended for his audience, and that wouldn’t make sense to the outsider they are supposedly speaking with.

This is not to say that evaluating bad arguments or pointing out fallacies is wrong. Getting to the truth is a worthy pursuit. The point is that we should strive to recognize the humanity of the people on the other side and treat them with compassion. This is understandably difficult because people on the other side are frequently anonymous, and they appear only as names and pictures above a line or two of diatribe.

Why do culture warriors mistreat the opposition?

Instead of seeing those on the other side as fellow children of God, culture warriors view their ideological opponents as threats to their most treasured worldviews. They have a competitive longing to win one for their team. And in this binary view of them and us, any disagreement can read as a challenge or even an insult.

When their enemies say or do anything that they interpret as menacing, their threat response is activated. During this process, blood flow to the brain decreases along with their ability to focus. Their blood pressure and negative emotions rise, and it becomes difficult to see the long-term consequences of their behavior. If the danger is large enough, they lash out. Latter-day Saints and other believers do not need to succumb to this threat response because their faith informs them of the long-term success of their cause.

Culture warriors’ hearts are at war. They are not open to learning from or connecting with those they perceive as enemies. They become combatants, often willing to engage in personal attacks and other dehumanizing behavior. More than anything, they want to win and feel vindicated. They may also desire to crush their enemy’s will and capacity to fight in the future.

Missionaries’ hearts are at peace

Because missionary work, by definition, requires interacting with those who see the world differently, the work involves a certain amount of conflict. Missionaries approach their conversation partners as equals and employ gentle persuasion. They do not manipulate or coerce.

Chel Owens is a good example of an online missionary. She has a modest online web series where she explains her beliefs and interacts with readers. What makes her messages effective is that she shares a part of herself and what has improved her life. She builds up her readers instead of tearing them down. She connects with them one by one in the comments.

Jesus Christ is a perfect example of a missionary. He spoke candidly to his enemies in public, even harshly at times. Yet, Christ was not a culture warrior. Yes, His messages benefited all those who heard Him, and he spoke of salvation and healing to his disciples, to those who wanted him dead, and to curious bystanders. He offered advice tailored to the needs of the scribes and Pharisees who so often harassed Him. If they had chosen to listen and follow it, their lives would have been blessed. Missionaries approach their conversation partners as equals.

Although missionaries do not always achieve their objective, they strive for unity and peace. They pray for and attempt to help those who disagree with them, even defending their enemies against hyperbole and unwarranted attacks. Missionaries know that the idle comments of Internet trolls cannot jeopardize God’s plans.

How do you avoid turning into a culture warrior?

To avoid becoming a culture warrior, it’s best to step back from conversations when you prioritize winning over helping your conversation partner, when you feel angry and want to retaliate, when you seek to crush an individual instead of evaluating their ideas, when you twist someone’s content instead of interpreting it positively, when you dehumanize your conversation partner, or when you prioritize likes over the person in front of you.

If you remain focused on building God’s kingdom by caring for others, you cannot become a culture warrior. While the desire to be respected, the competitive drive to win, and the urge to retaliate are all natural inclinations, there is more happiness and fulfillment in missionary work than there is in online battles. Servant-missionaries are more likely to find personal growth and closer relationships because they can connect with and maybe even learn from those who see the world differently.

The post Are You a Missionary or a Culture Warrior? appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →