by LaJean Purcell Carruth

The following is from LaJean Purcell Carruth’s presentation at BYU Education Week 2022 as part of the series presented on what can be learned from the Wilford Woodruff Papers.

Introduction

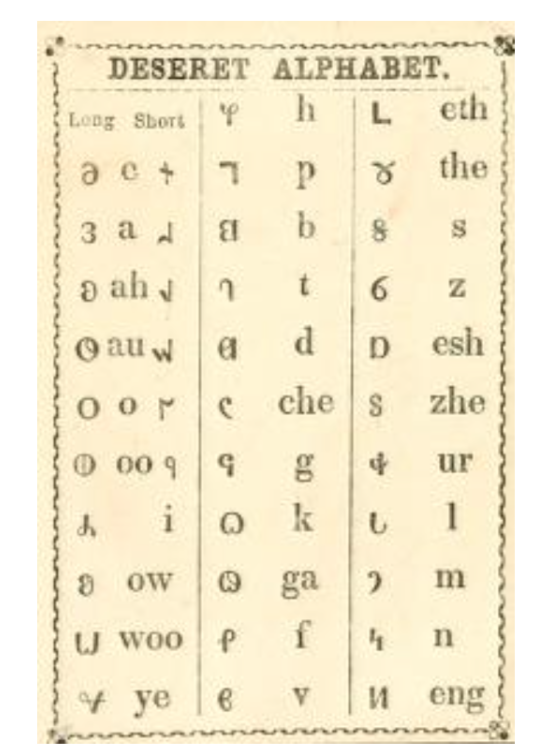

When I was eleven years old, I was bored one Sunday afternoon and found in my parents’ basement an old Improvement Era open to an article on the Deseret Alphabet.1 I was instantly, completely, absolutely hooked. I taught myself the Deseret Alphabet and decreed that I would be a Deseret transcriber when I grew up. Little did I know where that early passion would lead.

Another eleven years later, in 1974, I was finishing my first master’s degree at Brigham Young University in Library Science. I was on my own financially and desperately in need of work. A fellow student told me that a BYU professor, Dr. Thomas Alexander, was reading Wilford Woodruff’s journals, and that they contained some Deseret Alphabet entries. Dr. Alexander hired me to transcribe the Deseret Alphabet entries, fulfilling, in part, my childhood ambition, and giving me the paycheck I desperately needed.

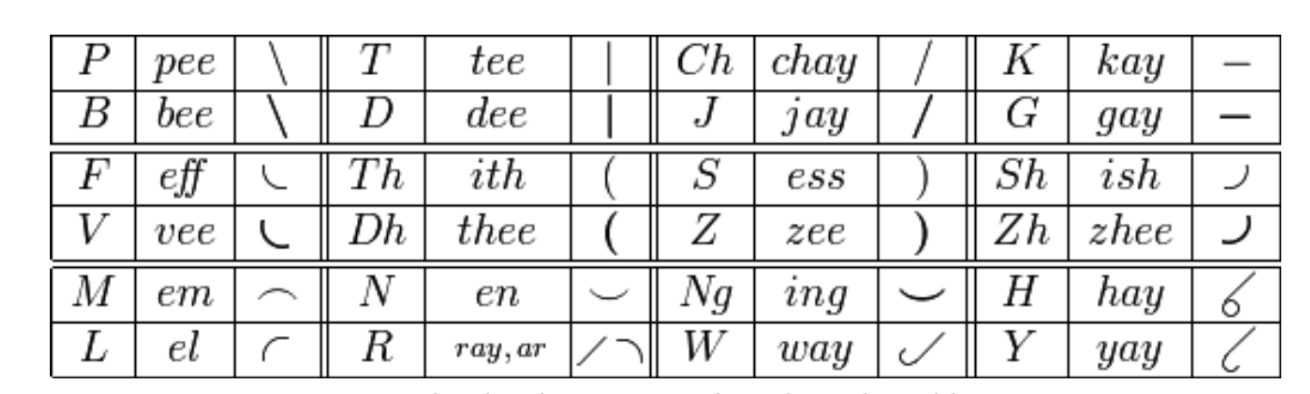

More work with the Deseret Alphabet came my way when I learned that Dennis Reilly, the manuscript librarian at BYU, had some items to transcribe. He told me that he didn’t have much in Deseret, but he had a lot of Pitman shorthand, what some might consider a precursor to the Deseret Alphabet. If I would learn to read Pitman shorthand, he’d give me a job. I didn’t quite realize what I was agreeing to, but I said, “Okay, I’ll learn Pitman shorthand.” I went out to the stacks and got a nineteenth-century book on Pitman and taught myself to read it. It wasn’t until many years later when I was trying to teach others to read this old shorthand that I realized how much I had actually accomplished at such a young age.

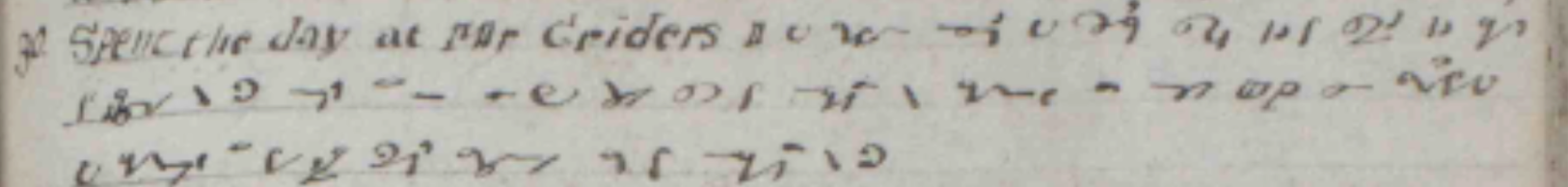

One of my first assignments for Dennis Reilly was to look at the shorthand in Wilford Woodruff’s journals on a microfilm copy. Wilford Woodruff did not write all his journal entries in shorthand, but instead what I call “salt and pepper shorthand,” a sprinkling of shorthand here and there throughout his writing. I began transcribing, but quickly found some shorthand I could not read at all. Months later, after extensive research and some help from the Phonographic Institute of Cincinnati, I learned that Wilford wrote in two different shorthands: Taylor shorthand, published by Samuel Taylor in 1786, and Pitman shorthand, published by Isaac Pitman in 1837. Other early Church leaders wrote in one or both of these, including some of Joseph Smith’s scribes who occasionally used Taylor shorthand in the prophet’s journals. These extant shorthand records are vital to the early history of the Church.

Wilford Woodruff’s Shorthand Writing

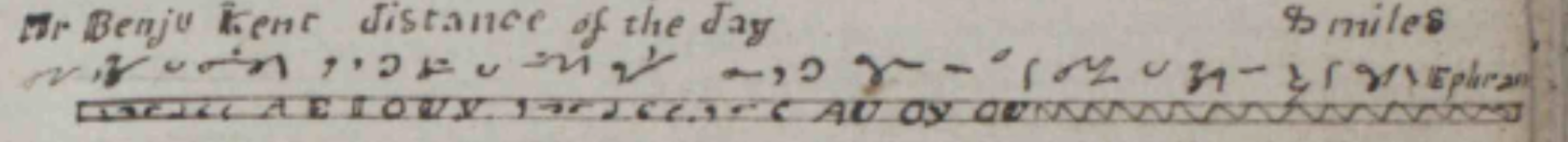

Elder Hale and myself had a good time in secret prayer. May God bless us on the islands and help us find the blood of Ephraim.

Note: Shorthand is in bold type and longhand is in regular type.

Wilford wrote some words in shorthand for convenience, especially some phrases such as “miles traveled,” which he recorded almost every day, and phrases such as “took the parting hand,” which is what he liked to say when he was bidding someone goodbye. I also realized he was writing in shorthand some names he used often. When I first started reading his shorthand I kept seeing a word spelled “f b” over and over and over, with no vowels to help, just “f b.” It took me a while to decipher, but then it dawned on me, “f b” was shorthand for his wife Phebe!

He also used shorthand for some things that were either deeply personal or that he didn’t want readily accessible to his readers. These included personal information, spiritual experiences, his private feelings, or problems with his wives.

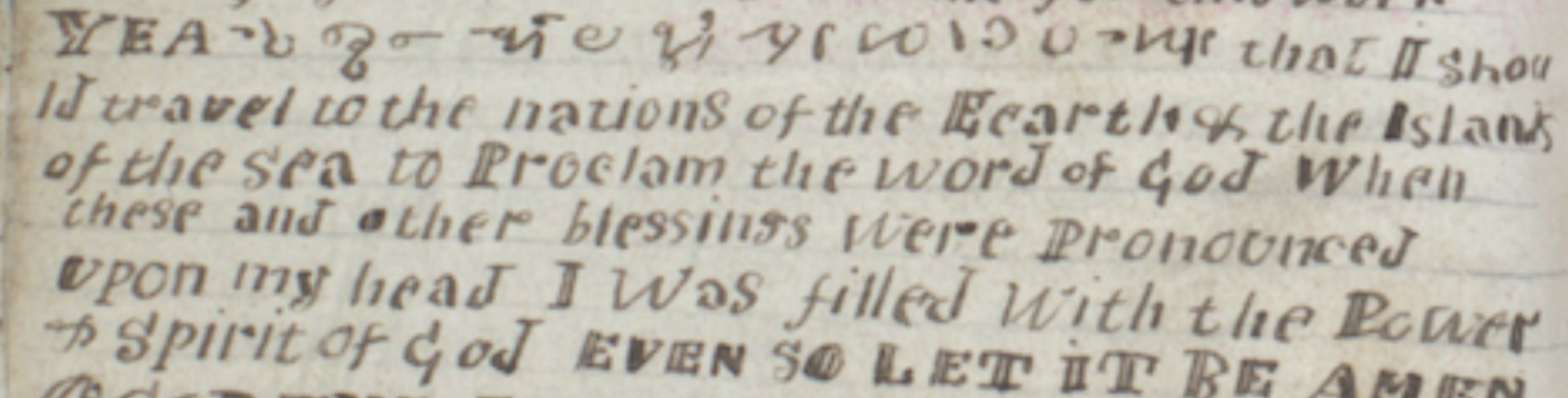

Many of his notations in shorthand are spiritual, some deeply so, and very personal. We see in this example that in part of the blessing he received from David Patten and Warren Parrish when he was ordained a Seventy, on May 31, 1836, he recorded in shorthand part of what must have been a very spiritual experience:

YEA even when my spirit was playing around the throne of God in eternity that I should travel to the nations of the Earth & the Islands of the sea to Proclaim the word of God when these and other blessings were Pronounced upon my head I was filled with the Power & spirit of God EVEN SO LET IT BE AMEN.

And again in this example from his mission to the Southern States, he wrote some of this spiritual experience in shorthand:

I and Brothers Smoot and Clapp went to the woods to pray. the power of God sat on us. we prayed with the spirit of prophecy. I sealed up my brethren and prophesied on their heads great blessings by the spirit of God.

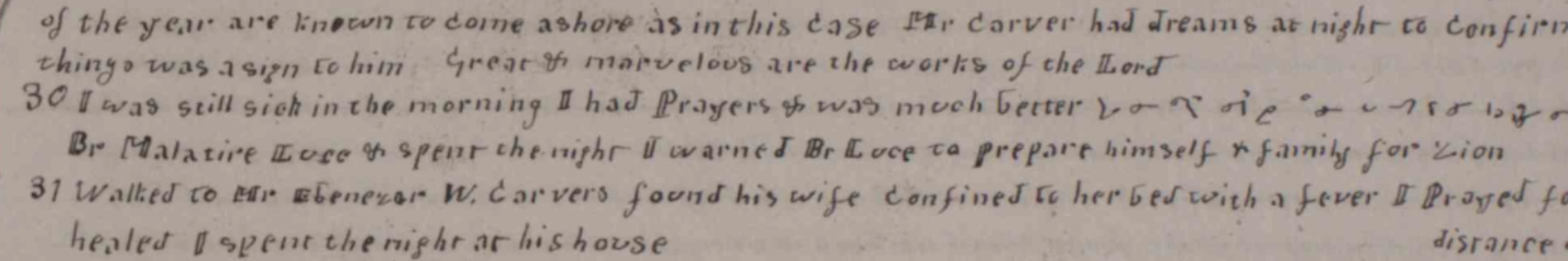

He also wrote in shorthand sometimes when he was sharing particularly tender experiences with his wife Phebe.

I was still sick in the morning I had Prayers & was much better after my wife laid hands on me and asked the Lord to heal me.

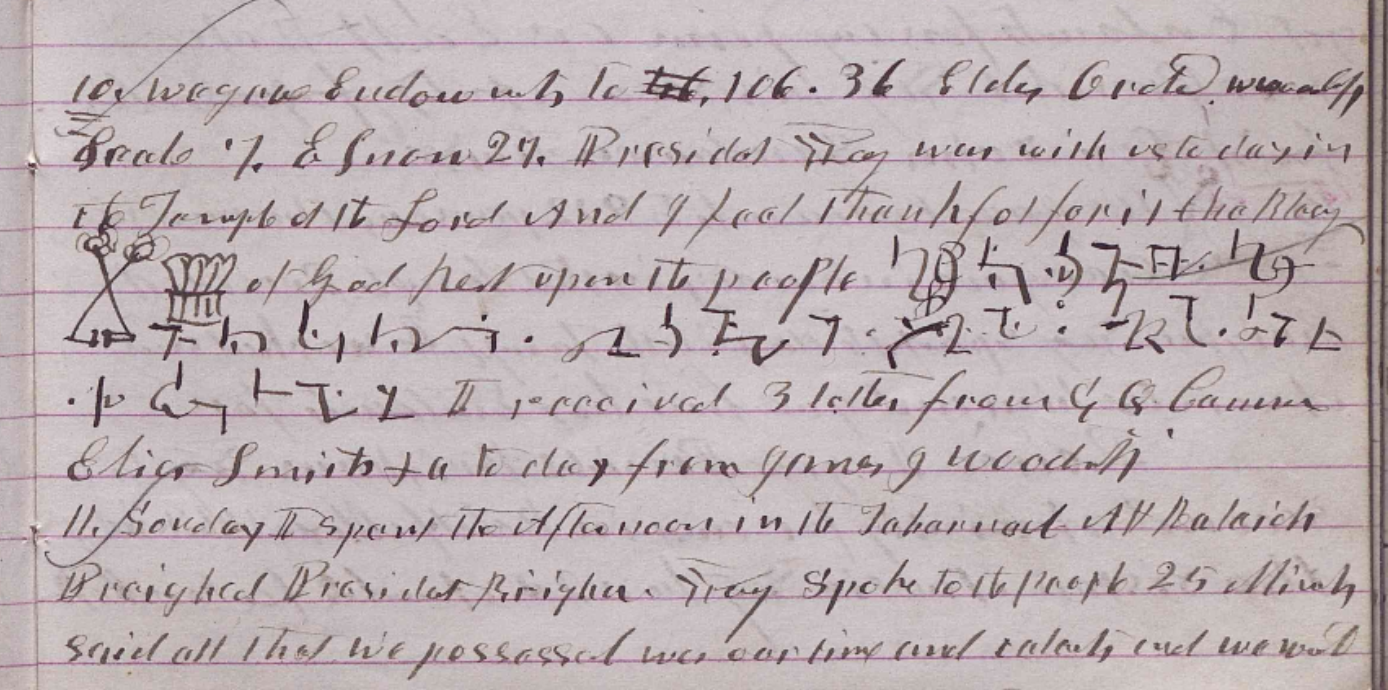

Besides such personal experiences, he sometimes wrote in shorthand when he knew that what he wrote could land him in legal trouble, as we see in this example of a plural marriage from March 10, 1877:

We gave Endowments to 106. 36 Elders ordained. W Woodruff sealed 7, E Snow 27. President Young was with us to day in the Temple of the Lord And I feel thankful for it. The Blessing of God Rested upon the people. President Young gave his daughter Eudora Young to me in marriage and sealed us together at the altar in the temple of the Lord this day and I thank the Lord for it[.] I received 3 letter from G. Q. Cannon Elias Smith &c to day from James J Woodruff.

George Watt and Conflicting Transcription

George Watt was the first British convert, baptized in 1837. Watt later came to Nauvoo where he taught Pitman shorthand. As a very skilled reporter, he recorded the trial of the murderers of Joseph and Hyrum Smith in Carthage Jail. Then he went on a mission from 1846 to 1851 back to England and Scotland. In late fall of 1851, he came to Salt Lake City traveling with Orson Pratt’s company and began reporting sermons, legislative proceedings, court reports, and other matters in Pitman shorthand.

It took me 30 years and thousands of hours working on other shorthand before I could figure out how to read George Watt’s shorthand. I had been working at BYU in the manuscripts department and had taken other freelance work, but needed more work, so I contacted the Church History Library, where I was hired to work on the John D. Lee trials: 1,400 pages of shorthand extant from John D. Lee’s two trials for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Through thousands of hours of work on that, I learned to read Watt’s shorthand.

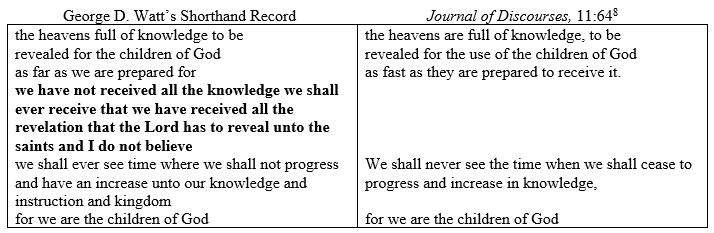

As the Mountain Meadows shorthand project slowed down, I was assigned to read other documents in George Watt’s shorthand, which is when I found out how very different his preserved transcript was from his original shorthand. The differences in the text published in the Journal of Discourses compared to his original shorthand became very obvious to me. As George Watt transcribed his shorthand, he would rewrite what was said rather than reporting word for word. George Watt was a brilliant writer, and he might have thought he was improving Brigham Young. But his additions and omissions changed the perception we have of Brigham Young. Brigham Young was a powerful and charismatic preacher, but when we read the accounts that Watt transcribed, we lose the power of his sermons.

For example, if Brigham said “heart,” Watt would replace that with “mind,” changing the meaning from one of spirit to one of intellect. Or when Brigham Young would so often address the congregation with a question, Watt would change that to a statement, thereby removing Brigham’s empathy towards the members, as we see in an example from 1853: President Young was discussing the hard crossing of the plains and how so many lost heart and almost lost their faith. He turned to the congregation and asked, “Do some of you who came over this year feel this way?” Watt, however, changed the text to, “Some of you who came over this year feel this way,” thereby telling the members how they felt rather than empathizing with them; the first shows understanding while the second shows accusation.7

Watt would also take out words that Brigham Young said and add words that Brigham Young never said, including whole paragraphs. Large sections in the Journal of Discourses have no relationship to the shorthand document. I wrote this short poem to exhibit Watt’s tendency to rewrite Brigham Young’s words:

There was a man named George Watt,

Who could improve Brigham Young, so he thought.

So he took out words here,

And he added words there,

And his accuracy was not what it ought.

Sermons published in the Journal of Discourses and in the Deseret News often differed from the shorthand, sometimes significantly; here is one example from a sermon by Wilford Woodruff on June 27, 1875, at the funeral of two young boys who had been burned to death:

The Lost Sermons: Never Transcribed or Published

While much of Watt’s transcription from his shorthand is heavily editorialized and incorrect, many of the early Church leaders’ sermons were never transcribed from the original shorthand. It was when I began transcribing these previously untranscribed sermons that I began to learn much about President Woodruff, about how he spoke, about the great dignity with which he spoke, and about his personal experiences, especially regarding the gospel.

From George Watt’s shorthand, I have recently transcribed this account from Wilford Woodruff’s record:

I even prayed before the Lord from time to time that I might live to behold a people who again embraced those principles and blessings I saw an account of recorded in the Bible . . . The Spirit of God bore record to me in my labors from time to time I [would] live to see that day that I should occupy a place in house of God behold a people who again embraced the gospel of Christ.9

Or this recently transcribed and unpublished record recorded in shorthand by John V. Long, a colleague of George Watt:

The Lord requires a great many things of us and the greater our blessings the greater will be our responsibilities to the Lord. The Lord will hold us responsible for all the blessings that he has given unto us he will hold us responsible for the gospel which he has revealed unto us for the use we make he will hold us responsible for the holy priesthood and the use we make of that and he will hold us responsible [for] all the truths of light and faith that has been given unto this people . . . It is a comfort to know that we serve a God whose attributes are good and righteous and to establish righteousness and truth upon the earth to do his mind and will to accomplish things necessary for the redemption of the earth for this reign and reign of his son Jesus Christ and the saints.10

These records of Wilford Woodruff show him as a man of great faith, someone who understood how to serve God and how to love the Savior and the gospel that was restored to the earth. Having accurate historical records matter. Knowing where the limitations are in our historical records matter. This is the Church of Jesus Christ and the focus needs to be on Him, not on misunderstanding; when we work from inaccuracies, we can sometimes get lost in clouded doctrine.

When we read Wilford Woodruff’s accurate record, we can see how he recognized the truth of the Savior that he was seeking. When we can focus on the correct doctrine, we can find the same truth.

ENDNOTES

- To learn more about the Deseret Alphabet, read “Deseret Alphabet,” Church History Topics, ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

- Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, August 20, 1837, p. 170, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, accessed August 16, 2023, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1837-08-20.

- Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, May 31, 1836, p. 85, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, accessed August 16, 2023, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1836-05-31.

- Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, June 30, 1836, p. 90, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, accessed August 16, 2023, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1836-06-30.

- Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, March 30, 1838, p. 25, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, accessed August 16, 2023, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1838-03-30.

- Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, March 10, 1877, p. 239, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, accessed August 16, 2023, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/journal/1877-03-10.

- LaJean Purcell Carruth, “Preached vs. Published: Shorthand Record Discrepancies,” August 18, 2020, history.ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

- Discourse by Wilford Woodruff, June 27, 1875, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, accessed August 17, 2023, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/discourse/1875-06-27.

- Church History Department Pitman Shorthand transcriptions, Wilford Woodruff, 1860–1872, April 6, 1860, ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

- Church History Department Pitman Shorthand transcriptions, Wilford Woodruff, 1860–1872, August 22, 1863, ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

LaJean Purcell Carruth is a senior historian at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City and an Advisor to the Wilford Woodruff Papers Project. She is the coeditor of Mountain Meadows Massacre: Collected Legal Papers (2017) and Liverpool to Great Salt Lake: The 1851 Journal of Missionary George D. Watt (2022).

LaJean Purcell Carruth is a senior historian at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City and an Advisor to the Wilford Woodruff Papers Project. She is the coeditor of Mountain Meadows Massacre: Collected Legal Papers (2017) and Liverpool to Great Salt Lake: The 1851 Journal of Missionary George D. Watt (2022).

To learn more about the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ and the never-before-published history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, please visit wilfordwoodruffpapers.org.

The post How One Woman’s Scholarship Helps Us Better Understand Church History appeared first on FAIR.

Continue reading at the original source →