The Know

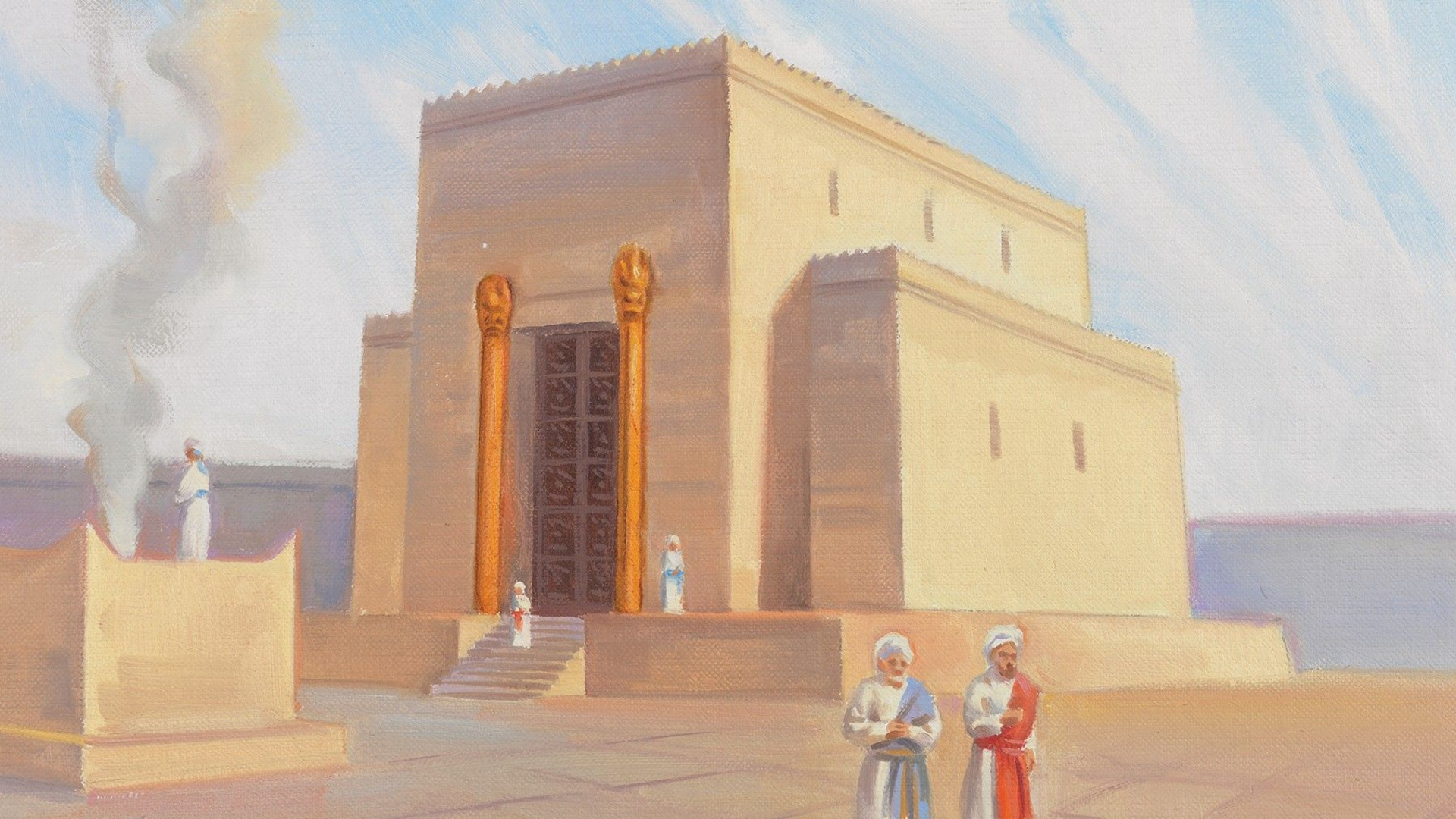

The Epistle to the Hebrews emphasizes many themes regarding the ancient temple that would have been intimately familiar to its audience. As noted by Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes, the focus on the temple highlights that “the temple sacrificial system was something of a moving concern for the audience of Hebrews” and that this audience “still retained a great deal of respect for the old covenant and the old law.”1

Chapters 8–10 especially discuss how the sacrificial system employed in the Israelite temple is fulfilled by Jesus Christ’s Atonement. In doing so, Hebrews depicts Jesus as “an high priest, who is set on the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in the heavens; a minister of the sanctuary, and of the true tabernacle, which the Lord pitched, and not man” (Hebrews 8:1–2). Jesus, our Great High Priest, then offered Himself as an infinite and eternal sacrifice that would allow us to enter the presence of God.

By stating that Jesus had entered “the true tabernacle,” the author of Hebrews is not saying “that anything about the Mosaic tabernacle was false, especially since it was Jehovah who commanded its building and revealed its ordinances. It means, rather, that the tabernacle was but a pattern or a type of the ‘true,’ or real, eternal heavenly realm.”2 In fact, the author of Hebrews will show that there is much good to be had in understanding the earthly shadows of heavenly things. As observed by Draper and Rhodes, “just as an outline or blueprint of an original source reveals much about it, so too do the tabernacle and the rituals performed therein, along with those who perform them, reveal much about the Lord and his ministry.”3

This can be seen as the author of Hebrews compares Jesus with the Levitical high priest, who oversaw the functions of the Israelite temple. This is especially manifest on the Day of Atonement, which was the one day a year that the Israelite high priest would enter the Holy of Holies “not without blood, which he offered for himself, and for the errors of the people” (Hebrews 9:7). Having entered the Holy of Holies, the high priest was then responsible for reconciling all of the house of Israel—himself included—to the Lord.

As this order of sacrifice on the Day of Atonement was modeled on “patterns of things in the heavens,” naturally the heavenly atonement would constitute a better sacrifice than anything the Israelites could do on earth (Hebrews 9:23). Similarly, while the high priest symbolically and ritually entered God’s presence by going into the Holy of Holies, Christ had actually entered heaven: “Christ is not entered into the holy places made with hands, which are the figures of the true; but into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God for us” (Hebrews 9:24). Jesus was also without sin and could therefore perform this infinite and eternal sacrifice. By contrast, “for all his holiness, the high priest himself was not without sin and therefore in need of expiation.”4

Jesus’s sacrifice also differed from the high priest’s sacrifice in another significant way: while the high priest would have to perform the same sacrifice “every year with blood of others,” Jesus was able to “put away sin by the sacrifice of himself,” and it was done only once (Hebrews 9:25–26). Because Jesus, “after he had offered one sacrifice for sins for ever, sat down on the right hand of God,” He is greater than the Levitical high priests (Hebrews 10:12). They, after all, could not perform any sacrifice of the same caliber as Jesus had performed.

Through His sacrifice, Jesus opened a way into heaven for all God’s children. Whereas only the Israelite high priest could enter the Holy of Holies in the Israelite temple, it is possible for all who repent and keep their covenants to have “boldness to enter into the holiest by the blood of Jesus, by a new and living way, which he hath consecrated for us, through the veil, that is to say, his flesh” (Hebrews 10:19–20).5 In other words, Jesus’s Atonement consecrates us to enter the Holy of Holies of the heavenly temple, thereby allowing us to enter the presence of God once more and serve in the same heavenly temple.

These verses also make a comparison between the veil of the temple and the flesh of Jesus Christ. This symbolism is especially clear when we understand that the veil is the entrance to the presence of God. And, because it is only through Jesus’s Atonement we are saved, His flesh would be a fitting description for the veil: only through His suffering and death can we be saved and enter the presence of the Lord, “allowing his mercy, grace, and power to flow into the lives of all those who would follow him, bringing to them forgiveness and the ability to live acceptably before the Father.”6

The Why

The temple, both ancient and modern, is focused on Jesus Christ. Everything that happens within those sacred walls is centered on Jesus Christ and His Atonement, providing a type and a shadow for us to refer to as we come closer to Him. Similarly, the covenants we make in the temple help us learn how to become more like Jesus as we strive to keep them throughout our lives.

As our Great High Priest, Jesus is able to mediate for us before God. He declared, “I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me” (John 14:6). He is the way into the Holy of Holies of the heavenly temple, and it is only through His Atonement that we can enter the presence of the Father to gain eternal life. Jesus stands ever willing and ready to help all God’s children enter His presence, and He will always be an advocate for those who come to Him, keep His commandments, and earnestly desire to become like Him.

Further Reading

Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes, Epistle to the Hebrews (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2021), 421–584.

Richard D. Draper, “‘By His Own Blood He Entered in Once into the Holy Place’: Jesus in Hebrews 9,” in Thou Art the Christ, the Son of the Living God: The Person and Work of Jesus in the New Testament, ed. Eric D. Huntsman, Lincoln H. Blumell, and Tyler J. Griffin (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 216–243.

- 1. Richard D. Draper and Michael D. Rhodes, Epistle to the Hebrews (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2021), 13.

- 2. Draper and Rhodes, Epistle to the Hebrews, 427.

- 3. Draper and Rhodes, Epistle to the Hebrews, 436.

- 4. Draper and Rhodes, Epistle to the Hebrews, 465.

- 5. The Greek word translated as “boldness” in the KJV also holds a nuance of being authorized to do something. Therefore, according to Draper and Rhodes, Epistle to the Hebrews,545, “They not only can approach God with confidence, but they are also authorized to do so.”

- 6. Draper and Rhodes, Epistle to the Hebrews, 547.

Continue reading at the original source →