The Know

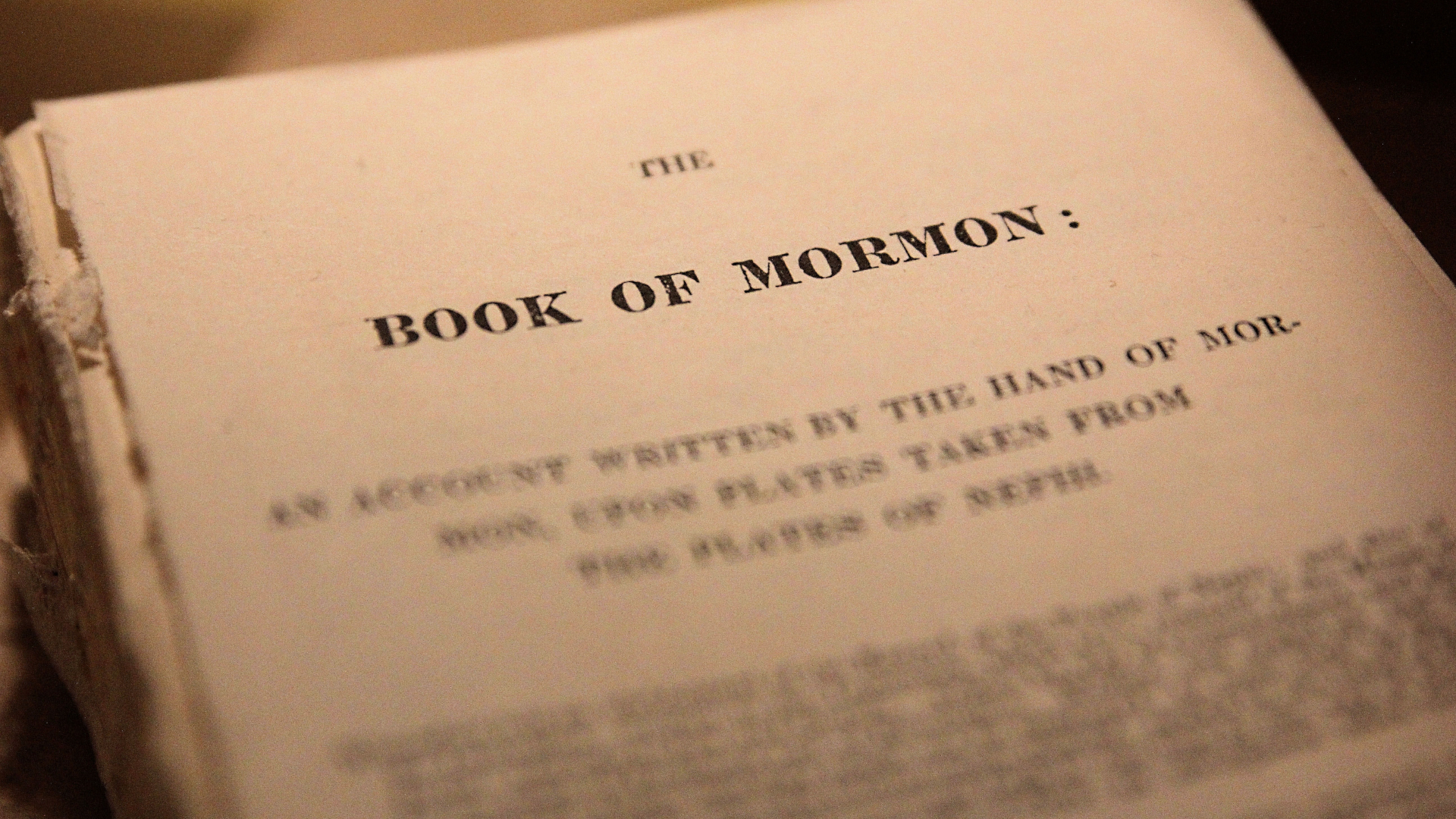

While the Book of Mormon was mostly compiled and abridged by the prophet Mormon, it was completed by his son Moroni following his death. As part of his additions, Moroni included a “title page,” which has been printed at the front of every edition of the Book of Mormon since 1830.1

Joseph Smith once explained that the Title Page “is a literal translation, taken from the very last leaf, on the left hand side of the collection or book of plates, which contained the record which has been translated.” Correcting those who assumed he wrote it himself, Joseph stated that the “Title Page is not by any means a modern composition either of mine or of any other man’s who has lived or does live in this generation.”2

According to the Title Page itself, there are two primary purposes of the Book of Mormon:

[1] to show unto the remnant of the house of Israel what great things the Lord hath done for their fathers; and that they may know the covenants of the Lord, that they are not cast off forever—And also [2] to the convincing of the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God, manifesting himself unto all nations

This twofold intent is clearly and repeatedly demonstrated throughout the text in a variety of different ways and through a number of different techniques.3 Some of the ways the authors illustrated these two core messages appear to reflect aspects of their ancient worldview, helping illustrate how the Lord “speaketh unto men according to their language, unto their understanding” (2 Nephi 31:3).4 Thus, understanding the worldviews that Nephites and their neighbors shared can provide insights into how the Book of Mormon fulfills these two purposes stated on the Title Page.

What Great Things the Lord Hath Done

The first of these purposes is “to show unto the remnant of the house of Israel what great things the Lord hath done for their fathers.” Throughout the Book of Mormon, many accounts of miracles, prophetic guidance, and divine covenants are given to that end.

Brant Gardner has noted that Nephite prophets “relied upon a cyclical concept of history that looked to the past to understand the future.”5 Such was the case for many ancient societies, including those described in the Old Testament. As explained by Geoffrey S. Spencer, the Old Testament could be as precise as it is regarding the future because its authors understood what God was doing for them in their day—and they expected the same pattern to play out in the future. That is to say, “History becomes prophetic because what God has done becomes the key to what he will do.”6

A similar belief was held in ancient America as well. Among the Maya, a cyclical calendar was used on the basis of repeating periods of five-, twenty-, and four-hundred-year periods.7 “The[se] cycles dominated Maya thought and resulted in a deterministic view in which history repeated itself. If a given day or period resulted in dreadful consequences once, it would do so again when the day returned or when the cycle repeated itself.”8 A similar system appears to be in use among the Nephites,9 and this conception of recurring history among the Maya certainly parallels the Israelite worldview of cyclical time , that the Nephites may have inherited.

According to Gardner, “showing what great things God had done for the Lamanite fathers was an explicit promise that those great things could and would be done for Mormon’s future audience.”10 As such, modern readers today can and should expect many of the same miracles and blessings that God’s people experienced in previous times.

The same can be applied to Mormon’s hope for future audiences to repent and make covenants with the Lord. When Mormon wrote his final words in the Book of Mormon, the Lamanites he knew “were long separated from the House of Israel. Nevertheless, Mormon showed that regardless of the time they might have spent away from the covenant, that covenant patiently awaited their repentance and return.”11

Throughout the Book of Mormon, it is made clear how the Lamanites had previously fallen away from the covenants they had made with the Lord near the beginning of their exodus to the Americas. However, Mormon also showed throughout his record that the Lamanites could repent of their sins and rejoin the Lord’s covenant family—as expressed most dramatically in the stories of the Anti-Nephi-Lehies and the missionary journey of the brothers Nephi and Lehi in Helaman 5. As such, Mormon shows his hope for future readers to follow this cycle and repent: Just as these two groups of Lamanites “did lay down their weapons of war, and also their hatred and the tradition of their fathers” (Helaman 5:51), Mormon hoped that Lehi’s future posterity who “were plausibly immersed in a culture of war and bloodshed” would similarly “lay down your weapons of war, and delight no more in the shedding of blood, and take them not again, save it be that God shall command you” (Mormon 7:4).12

Showing that Jesus is the Christ

For the Book of Mormon’s primary authors and editors, persuading readers to believe in and come unto Jesus Christ was a significant priority.13 While any reader of the Book of Mormon can be enlightened by this added witness of the ministry and divinity of Jesus Christ,14 it is telling how Mormon and Moroni expressly tailored their words for future Lamanites, whom they likely presumed would have had similar cultures and beliefs as the Lamanites known to them in their day. As such, many aspects of the teachings about Jesus in the Book of Mormon reflect ancient understandings of God in both an Old and New World setting.

For example, multiple prophets are reported as having seen God and Jesus Christ in divine visions, beginning with Lehi in 1 Nephi 1. In fact, as Nephi recounts how his father was called to be a prophet, he follows the same narrative pattern in describing this experience as found in the experiences of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and other Old Testament prophets.15 Remarkably, many later prophets who had lived in the New World their entire lives recount their visions in different ways, which Mark Alan Wright has observed “conform to a pattern that can be detected in ancient Mesoamerica.”16

Specifically, “Elements of this pattern can be seen throughout the Book of Mormon in the accounts of individuals who are overcome by the Spirit to the point that they fall to the earth as if dead and ultimately recover and through that process become spiritually reborn and subsequently prophesy concerning Jesus Christ,” which mirrors the calling of Mesoamerican shaman-priests. Oftentimes, this event also began as the newly called prophet’s “soul embarked on a spirit journey while his body lay suffering,” just as experienced by Alma and King Lamoni in the Book of Mormon (see Mosiah 27:19 and Alma 18:42).17 Upon reawakening, both Alma (Alma 36) and Lamoni (Alma 19:12–13) became witnesses of Christ.

Other teachings by Nephite prophets clearly reflect an ancient Mesoamerican setting. For example, in Alma 34, Amulek describes the Atonement as neither the “sacrifice of man, neither of beast, neither of any manner of fowl,” but an infinite and eternal sacrifice of the Son of God Himself (Alma 34:10). The three types of sacrifice Amulek specifically taught would be inadequate—humans, beasts, and birds—happened to be “the three most common things that were offered by Mesoamerican worshipers” that an apostate group such as the Zoramites would have likely been familiar with due to their neighboring civilizations.18

Similarly, Wright has also observed that it is possible that Jesus “may have been communicating with [the Nephites] according to their cultural language when he invited them to come and feel for themselves the wounds in his flesh.”19 Unlike His appearance in the Old World, where “he invited them to touch solely his hands and feet (Luke 24:39–40),” Jesus invited the Nephites to first feel the wound in His side (see 3 Nephi 11:14). As Wright observes, “To a people steeped in Mesoamerican culture, the sign that a person had been ritually sacrificed would have been an incision on their side—suggesting they had had their hearts removed,”20 therefore showing how Jesus identified Himself to the Nephites in a way that they would have culturally understood.

The Why

As John W. Welch has observed, the title page “clearly articulates the essentials of the Book of Mormon.”21 It provides a clear introduction to the overarching purposes of Mormon’s abridgement and informs the reader early on why the Book of Mormon is so important for the world today as we strive to come closer to Jesus Christ ourselves.

Ultimately the title page allows readers to “know, of a surety, the unambiguously good intent of the Book of Mormon, written unto the convincing of all people that Jesus is the Christ, the eternal God, manifesting himself to all nations, so that people may know and embrace the mercies and covenants of the Lord, who desires all to come unto Him.”22 As modern readers approach the Book of Mormon with an open heart and mind, they, too, can be enlightened by the Spirit and come away with a deeper appreciation for this sacred book of scripture.

Further Reading

Brant A. Gardner, Engraven upon Plates, Printed upon Paper: Textual and Narrative Structures of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2023), 195–214.

John W. Welch, Inspirations and Insights from the Book of Mormon: A Come, Follow Me Commentary (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2023), 1–4.

Robert J. Matthews, “What the Book of Mormon Tells Us about Jesus Christ” in The Book of Mormon: The Keystone Scripture, ed. Paul R. Cheesman (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 21–43.

- 1. Although the Book of Mormon does not identify the author of the Title Page itself, Joseph Smith attributed this page to the prophet Moroni in the 1840 edition of the Book of Mormon. Given its placement as the last leaf of the gold plates, and its reference to being hidden by Moroni, this attribution by Joseph Smith would appear internally consistent with the Book of Mormon narrative. See John W. Welch, Inspirations and Insights from the Book of Mormon: A Come, Follow Me Commentary (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2023), 1. For additional discussion and commentary on this matter, see Clyde J. Williams, “More Light on Who Wrote the Title Page,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 2 (2001): 28–29, 70; Sidney B. Sperry, “Moroni the Lonely: The Story of the Writing of the Title Page to the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4, no. 1 (1995): 255–259; David B. Honey, “The Secular as Sacred: The Historiography of the Title Page,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 3, no. 1 (1994): 94–103; Daniel H. Ludlow, “The Title Page,” in The Book of Mormon: First Nephi, The Doctrinal Foundation, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1988), 19–34.

- 2. History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834], p. 34, The Joseph Smith Papers. Concerning the Book of Mormon’s placement at the end, rather than the beginning of the text, see Evidence Central, “Book of Evidence: Subscriptio,” Evidence 75, September 19, 2020. See also, Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Colophons (Antiquity),” Evidence 245, September 27, 2021.

- 3. Demonstrating this, the Title Page also draws upon language found throughout the Book of Mormon, providing rich intertextuality to remind readers of the Book of Mormon’s purpose as they read. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Title Page Intertextuality,” Evidence 425, November 15, 2023. For an additional discussion regarding Mormon’s purposes in compiling the Book of Mormon, see Book of Mormon Central, “What Was Mormon’s Purpose in Writing the Book of Mormon? (Mormon 5:14),” KnoWhy 230 (November 14, 2016).

- 4. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does the Lord Speak to Men “According to Their Language”? (2 Nephi 31:3),” KnoWhy 258 (January 6, 2017).

- 5. Brant A. Gardner, Engraven upon Plates, Printed upon Paper: Textual and Narrative Structures of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2023), 195.

- 6. Geoffrey F. Spencer, “A Reinterpretation of Inspiration, Revelation, and Scripture,” in The Word of God: Essays on Mormon Scripture, ed. Dan Vogel (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1990), 24.

- 7. For further discussion on these time cycles, especially as they could also relate to the Book of Mormon, see Mark Alan Wright, “Nephite Daykeepers: Ritual Specialists in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” in Ancient Temple Worship: Proceedings of the Expound Symposium, 14 May 2011, ed. Matthew B. Brown, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Stephen D. Ricks, and John S. Thompson (Salt Lake City and Orem, UT: Eborn Books and Interpreter Foundation, 2014), 253; John E. Clark, “Archaeological Trends and Book of Mormon Origins,” in The Worlds of Joseph Smith: A Bicentennial Conference at the Library of Congress, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2005), 90; John E. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 2 (2005): 47.

- 8. Kaylee Spencer-Ahrens and Linnea H. Wren, “Arithmetic, Astronomy, and the Calendar,” in Lynn V. Foster, Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2002), 247.

- 9. For another possible use of these cycles of time among Nephite and Lamanite thought, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Samuel Make Such Chronologically Precise Prophecies? (Helaman 13:5),” KnoWhy 184 (September 9, 2016).

- 10. Gardner, Engraven upon Plates, Printed upon Paper, 202.

- 11. Gardner, Engraven upon Plates, Printed upon Paper, 212.

- 12. Gardner, Engraven upon Plates, Printed upon Paper, 214. The trend of evidence for widespread warfare in ancient Mesoamerica is consistent with the picture of recurring conflicts in the Book of Mormon, where serious wars were known from an early period and were fought for a variety of reasons. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Changing Views of Mesoamerican Warfare,” Evidence 209, June 28, 2021.

- 13. See 1 Nephi 6:4; 1 Nephi 19:23; 2 Nephi 25:18, 23; 26:12; 30:7; 33:4, 10; Jacob 1:7–8; 4:4; Words of Mormon 1:8; 3 Nephi 5:26; Mormon 3:21–22; 5:14; 7:5, 10.

- 14. See Robert J. Matthews, “What the Book of Mormon Tells Us about Jesus Christ” in The Book of Mormon: The Keystone Scripture, ed. Paul R. Cheesman (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 21–43 for a greater discussion on how the Book of Mormon invites all readers to learn more about Jesus Christ and His Gospel.

- 15. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Lehi’s Prophetic Calling (Overview),” Evidence 345, June 7, 2022 and its subsequent, more detailed entries for more details. See also Stephen D. Ricks, “Heavenly Visions and Prophetic Calls in Isaiah 6 (2 Nephi 16), the Book of Mormon, and the Revelation of John,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 171–190 and Stephen O. Smoot, “The Divine Council in the Hebrew Bible and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 27 (2017): 155–180 for additional analyses of these visions in an Old World setting.

- 16. Mark Alan Wright, “‘According to Their Language, unto Their Understanding’: The Cultural Context of Hierophanies and Theophanies in Latter-day Saint Canon,” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 3 (2011): 59.

- 17. Wright, “According to Their Language, unto Their Understanding,” 59, 63.

- 18. Mark Alan Wright, “Axes Mundi: Ritual Complexes in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 12 (2014): 89. For more discussion on this topic, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Must There be an Infinite and Eternal Sacrifice? (Alma 34:12),” KnoWhy 142 (July 13, 2016).

- 19. Wright, “Axes Mundi,” 90–91.

- 20. Wright, “Axes Mundi,” 91.

- 21. Welch, Inspirations and Insights from the Book of Mormon, 3.

- 22. Welch, Inspirations and Insights from the Book of Mormon, 4.

Continue reading at the original source →