An informed confidence looks like irrationality to people who don’t possess it.

Sometimes, that assessment of irrationality is accurate because confidence really can be the product of delusional thinking. But history is replete with examples of people whose convictions were deemed to be irrational until they were manifest in real events, turning upside-down the conventional wisdom of what is rational.

Years ago, when I was in college, I had a summer job in California. One day at work, I spoke with a co-worker, and our conversation steered toward religion. I let her know I was a Latter-day Saint, and she bluntly told me that she hated my faith. When I asked her why, she mentioned our missionary program. She was a close friend to a family where a young man had joined the Church and decided to serve a mission. In conversations with his mother, she could not comprehend how her child would accept an arrangement where he would only be allowed to talk with her on the phone twice a year (which was our missionary policy at the time). An informed confidence looks like irrationality

This conversation occurred only a few years after I returned from my own mission when I could not fathom any critique of the mission experience. My mission was so important and so formative to me that in response to hearing my co-worker’s thoughts, I simply had no words. I thought of the young man who she described and contemplated the deep gulf in perspective between him and his mother.

To rephrase my opening premise—a person who is uncertain, equivocating, or doubtful will mistake another person’s informed confidence for irrationality. This divide in perspective explains disparities in how people evaluate decision-making at the highest levels of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Investment may be a good metaphor for illustrating this truth. For example, if I were to accumulate large tracts of barren land against the advice of professional investors, observers might see my behavior as some combination of reckless, clueless, or arrogant. They might see my investment strategy as analogous to a stubborn poker player who refuses to admit the weakness of his hand.

But suppose I and my critics have a mismatch of information. Unlike my critics, I know that there is an abandoned mine in the area with minerals that will be in high demand in coming years. The mine is likely to be reactivated, with a need for the building of highways and towns and supporting infrastructure on the surrounding land. If my critics were to become aware of all of this same information, they would quickly understand my land investment choices to be not outlandish, not stubborn, not reckless, but perfectly rational.

This metaphor applies to the Church’s investments in temples, and critics’ negative reactions to those investments reflect a mismatch in information. That problem of mismatch is seen in broader Judeo-Christian history in the story of Elijah’s dramatic confrontation with the priests of Baal and later in many early Christians’ decisions to follow their Lord in martyrdom. Latter-day Saints see the dedicatory prayer of the Kirtland temple, documented in restoration scripture, as an echo of the dedicatory prayer of Solomon’s temple. To an observer, that might seem bold or even audacious on the part of Joseph Smith, but that assessment reflects a mismatch in information.

Yale professor Harold Bloom famously wrestled with this in his book The American Religion, where he analyzed Joseph Smith from the perspective of an agnostic Jewish critic of religion. In numerous passages, he offered iterations of this assessment:

What is clear is that Smith and his apostles restated what Moshe Idel, our great living scholar of Kabbalah, persuades me was the archaic or original Jewish religion, a Judaism that preceded even the Yahwist, the author of the earliest stories in what we now call the Five Books of Moses. To make such an assertion is to express no judgment, one way or the other, upon the authenticity of the Book of Mormon or of the Pearl of Great Price. But my observation certainly does find enormous validity in Smith’s imaginative recapture of crucial elements in the archaic Jewish religion, elements evaded by normative Judaism and by the [Christian] Church after it.

Bloom’s analysis reflects a good faith effort to account for Joseph Smith’s extraordinary achievements, and he regards the Kirtland temple manifestations as “peak experiences” that amount to a source of Joseph’s authority. In this, he is partially correct; in 1880, Eliza R. Snow would offer in a poem that the temple “testifies that Joseph Smith, the great, and good, and wise, is God’s true prophet.” This resonates as a simple claim, but the verse points to something much more profound: the temple is central to Latter-day Saint epistemology. It is simply not possible to understand the depth of Latter-day Saint religious convictions without seriously engaging with our experiences in temples. Where Bloom erred was in his characterization of Kirtland’s “peak experiences.” Elder Boyd K. Packer openly refuted this assumption in 1993, clarifying that most of our subsequent experiences are not published. What I earlier described as a mismatch in information is, to some extent, by design; we are reminded that Isaiah’s great temple theophany was accompanied by injunctions toward discretion based on receptivity.

In 1994, Elder M. Russell Ballard offered public remarks that help to convey the real nature of questions surrounding temples:

During the Orlando temple tours, I explained to our guests who were not of our faith that I understood if they found this message a bit overwhelming. I taught my new friends in Orlando, as I teach here this morning, that either the gospel has been restored or it has not. Either the Savior’s original church and its doctrine were lost or they were not. Either Joseph Smith had that remarkable vision or he did not. The Book of Mormon is another testament of Jesus Christ or it is not. Either the fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ was restored to earth through God’s chosen latter-day prophet or it was not. The truth really is not any more complicated than that. Either these things happened just as I have testified or they did not.

It is fitting that Elder Ballard was referencing remarks he made during a temple open house because Latter-day Saint temples really do present church members and observers with this simple binary: are temples really what we claim them to be? It is true that temples are expensive, ornate, and labor-intensive to build and operate. Among religious groups, some investment decisions around facilities seem questionable until we observe their value in creating cohesion in the community. But the participation-narrowing recommend process puts Latter-day Saint temples in a different category altogether. If their purpose were to simply create cohesion among believers, well, most people might assume that there are easier and cheaper ways of creating cohesion. Critics’ negative reactions reflect a mismatch in information.

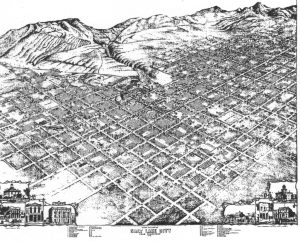

Caption: The spiritual unity in the temple, motivated efforts for the United Order

For Americans with progressive yearnings for an egalitarian society, it might be a surprise to know that conservative-leaning Utah holds the country’s highest concentration of citizens whose ancestors have actually attempted to live in a communal framework. Made possible through sacred temple covenants, the “United Order” is a deep cultural memory that persists among church members into the present day. The basis for “Zion” community is shared experience of God.

Among Latter-day Saints who take the temple experience seriously, this leaves a deep impression. And as Joseph Smith expressed at multiple points in the dedicatory prayer of the Kirtland Temple, the prophetic intention is for saints to be transformed by their temple experience and then turn outward to impact the world. When this happens, we rightly expect to see more cohesion and upward mobility in communities with Latter-day Saint influence.

But once again, is it possible for religious groups to achieve this kind of cohesion and community impact using fewer resources through shared experiences like potlucks in parks? I would suggest that the honest answer, the one dreaded by nonbelievers in particular, is no. The basis for what Latter-day Saints call “Zion” community is a shared experience of God, not a humanistic vague togetherness. Temples are impactful not because they are lovely places for gathering, but rather due to our shared conviction articulated by President Russell M. Nelson, that “A temple is literally the house of the Lord.”

This is the reality that animated the sacrifices of early Latter-day Saints in the construction of the Kirtland temple and subsequent temples. Temple-related sacrifices came in response to revelation through Joseph Smith, but the core principle of communal religion that made any of those experiences possible might be best articulated in the Book of Mormon’s description of a people who were “all converted unto the Lord” and because of that unifying fact “they had all things in common among them.”

That vertical dimension of our temple experience is essential to the horizontal experience of connection to community that temples provide. Temple-going Latter-day Saints have forged bonds of community connection through group temple trips, through service alongside other members of the community as temple workers, and through assisting with each other’s ordinance work for ancestors. When I go to the temple with friends to do a single baptism for one of my ancestors, no less than four other individuals join in that experience, sharing in my connection to God and sharing in my connection to a soul who has gone before us. In a time where the U.S. Surgeon General has written an entire book lamenting the destructive health impacts of widespread lack of human connection, the Latter-day Saint temple experience stands as a countercultural beacon of connectedness. The highest of human goods are not attainable without holiness.

But even believing members like myself are sometimes amazed at the sheer scale of our temple building. Even with firm convictions of the objective validity of our temple work, the pace of building sometimes feels daring, bold, and even audacious. I interpret that as a challenge to members of the Church, and I suspect it is an indicator of the depth of personal conversion that will be required of us in the days ahead. The future will be characterized by continual movement toward clarity, and for Latter-day Saints, the temple experience will be a core factor in the development of that clarity.

Outside of our temples, a number of groups are trying to realize various competing visions of ideal society. Some of these visions are based around notions of order; others are based around notions of fairness, progress, or self-fulfillment. The most fiercely advocated of these visions are offered with the delusional premise that the highest of human goods are attainable without holiness, the behaviorally evident love of God that allows for true love of neighbor. Latter-day Saints see these delusions confronted and challenged most clearly in our participation in the temple, in the glimpse of connection and holiness and cooperative sociality experienced within those walls. Taking that temple experience outward and reflecting temple ideals in our spheres of influence beyond temple walls is the great and audacious challenge for Latter-day Saints now and into the future.

The post The Audacity of Temples appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →