The poet Guillaume Apollinaire coined the word surreal (“beyond reality”) in 1917 to describe irrational, illogical, and dreamlike art expressing the unconscious mind. We now use surreal to mean “strange; not seeming real; like a dream.” We often choose “surreal” to explain the incongruence of sudden trauma, like the loss of a loved one. Life no longer seems real; it feels like a dream or, often, a nightmare. There’s the sense that you’re going to wake up at some point. It feels, well, surreal.

“Surreal.” That’s all my mind could conjure on the morning of September 11, 2001. I was sitting in the waiting area of the old Moran Eye Center on Salt Lake City’s east bench. The entire wall across from me was a window, giving me a majestic view of the entire valley below. I was watching plane after plane glide from left to right and land at the Salt Lake International Airport. “So many planes.” Each one’s descent caused me to descend into greater anxiety and fear.

When I arrived to have the stitches removed from the corneal transplant in my right eye, everything already felt surreal. I had already heard the news of the second plane striking the World Trade Center and knew our nation was under attack. Just as I sat down in the waiting room, news broke of yet another plane hitting the Pentagon. “Surreal.” Then, the South Tower collapsed. I remember watching the inverse mushroom cloud engulf Lower Manhattan and thinking, “How is that even possible? There must be tens of thousands dead.”

While all civilian flights were being forced to land, reports continued of other hijacked aircraft. My eyes kept switching from the television to the endless parade of planes crossing the valley. From my vantage point, each one seemed headed straight for the Church Office Building of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with its eerily similar architecture to the Twin Towers. “Is one hijacked?” Fear overwhelmed me. “This can’t be happening. Surreal.” Suddenly, loud gasps, including mine, filled the room as the North Tower collapsed. Everyone reflexively looked at one another, confusion, shock, almost desperation, in our eyes. “What’s next? Surreal.” The tragedy of 9/11 was a surreal nightmare.

“Dr. Lundergan,” I said, “I can wait or come back another day.” This stoic professional broke down, dropping the tweezers as her hands sought unsuccessfully to hide her tears. I stood up and weakly offered, “It’s OK. We’re all having a really bad day.”

“No, no. My husband is still on a plane,” she blurted out between deep sobs. His flight had departed from Boston, the same airport as the first hijacked airliner. My heart filled with sympathy and sorrow. I embraced her, a relative stranger, and tried my best to reassure her. After a few moments, she excused herself.

Sometime later, Dr. Lundergan returned relieved, even joyful. Her husband had called her from Chicago, where his flight had landed. Her expert hand steadily removed the stitches on my eye. I thanked her, and she, embracing me this time, replied, “And thank you.”

As I returned to work, that tender moment gave me some momentary hope. It was soon dashed by fear and anxiety as I listened to the news and worried about the world my young sons would inherit. I drove past the World-Trade-Center-look-alike Church Office Building, with hundreds of evacuated employees fleeing to safety. As my anxiety deepened, I saw the Salt Lake Temple. At that moment, I felt the words, “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid.” That intense feeling of “the peace of God, which passeth all understanding” filled my heart and mind. It was, well, surreal—beyond reality.

Surrealism’s greatest advocate, André Breton, described the movement as a way “to resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality.” The tragedy of 9/11 was a surreal nightmare, yet what followed in the days, weeks, and even months was a surreal sense of national unity. It seemed the “resolving” of raw reality with the elusive dream of a people “of one heart and mind,” “having their hearts knit together in unity,” with “no contention one with another” who “mourn with those that mourn; who “are willing to bear one another’s burdens,” and who “[dwell] in righteousness.”

America experienced a strong trauma bond, from the tens of thousands directly affected by the attacks to the hundreds of millions who experienced it through media coverage. In Pew’s survey just days after the attacks, 92% of Americans responded they felt sad, 77% felt frightened, and 71% felt depressed. Yet, three weeks later, the rates had already halved. As a nation, we “mourned with” and “comforted” one another.

Much of this healing came from a nation turning to God with “hearts knit in prayer,” greater religious observance, and most importantly, an increase in character “righteousness.” Before the attacks, Pew found that only 37% felt religion’s role in American life was increasing. A month after 9/11, that number was 78%, the highest ever recorded. Furthermore, in a survey following the attacks, 69% responded that they prayed more, and 16% that they attended religious services more.

Most importantly, the character of the nation improved. As one study showed, people exhibited sharply increased “gratitude, hope, kindness, leadership, love, spirituality, and teamwork” in the immediate aftermath of the attacks. Diminished, yet still elevated levels persisted even 10 months later. The authors wrote, “The theological virtues allowed people to enhance their sense of belonging in ways that could be self-perpetuating. In the immediate aftermath of September 11, people behaved differently by turning to others, which in turn changed their social worlds so that the relevant behaviors were rewarded and thus maintained.”

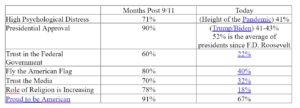

Politically, the nation was of “one mind.” George W. Bush, the winner of a controversial election, saw his approval rating go from 50% to an astounding 90%, again, the highest ever recorded. Patriotism soared. Eighty percent of citizens displayed an American flag outside their residence. Levels of trust in the federal government hit 60%, a number not seen since 1968. News organizations received a record 70% approval.

That unity even spread to other nations. It was most palpable when Salt Lake City hosted the 2002 Winter Olympics just five months after 9/11. On the evenings my wife and I attended the medal ceremonies downtown, I remember the strong feeling of solidarity between people from all across the world. The intense unity in the opening and closing ceremonies was unforgettable. I remember thinking, “This is how Zion will be; this is how the Millennium will feel.”

On the one-year anniversary of 9/11, while the intensity of the unity had faded, its afterglow was still vibrant. In a devotional that night, then-church president Gordon B. Hinckley noted, “We know that much good has come of these dreadful circumstances. From the smoke and ashes of New York, Washington, D.C., [and] Pennsylvania…has arisen a greater sense of unity and purpose.” In that same meeting, James E. Faust noted, “These ignoble acts of terrorism reawakened in all of us an appreciation for our blessed land. Out of this disaster have come hundreds of stories of courageous acts of unselfishness and heroism.”

September 11 is officially Patriot Day and a Day of Service and Remembrance. We who lived through that time surely remember the surreal nightmare of 9/11, the stories of the courageous, patriotic men and women of that time, and especially the memories of the victims. The National September 11 Memorial Museum’s motto, taken from the Aeneid, declares in large letters of recovered World Trade Center steel, “No Day Shall Erase You From the Memory of Time.”

Tragically, however, the surreal national unity was erased, or as another society once proclaimed, “ZION IS FLED.” The chart below demonstrates just how far we are from those precious months of national unity, patriotism, and loving service.

There are many reasons that our surreal unity evaporated. Chief among them was how short-lived the post-9/11 religious revival was. A study on young adults’ responses to 9/11 put it best. The attacks “exerted only modest and short-lived effects” on religiosity and spirituality. What it said of young adults was true for most of the populace. “[T]urning toward religion simply helped them get through the aftermath of the event, but was not something that resulted in any considerable religious or spiritual change.” Later polling demonstrated that it was “largely those already highly religious” whose increased religiosity and spirituality endured.

In the Book of Mormon, the Nephite civilization repeatedly went through similar experiences. After a period of prosperity, peace, unity, and righteousness, pride led society into “ranks” or “classes” based on wealth, education, and political power. As a result, internal discord brought civil wars and/or societal weakness that enemies exploited with war. Following those societal traumas, the humbled people generally repented and found a new season of peace and unity—only to fall again. This seems the reality of not just Nephite history, but history in general. An enduring period of unity and peace for a people or a nation is truly surreal—“beyond reality.”

And yet, many of us experienced it, if only briefly, after 9/11. While we were “compelled to be humble,” most Americans chose “repentance,” and chose to change. We passed, again, if only briefly, what Elder Dale G. Renlund in 2021 likened to a cardiac stress test. However, our society has transformed greatly since 2001. Many cultural, religious, political, technological, and institutional changes have left us fractured like the late 1960s and early 1970s, if not the late 1850s.

As a nation, we generally failed the 2020 pandemic and presidential election stress test. Divisiveness, distrust, and anger have all increased dramatically. The results were mixed and certainly not good enough within the Church. As Elder Renlund put it, “The spiritual stress test [of the pandemic/political environment] has shown tendencies toward contention and divisiveness. This suggests that we have work to do to change our hearts and to become unified as the Savior’s true disciples.” Cultural, religious, political, technological, and institutional changes have left us fractured.

There will continue to be societal stress tests until He comes whose right it is to reign. Along with many others, I believe the next six months will be one of those tests. Regardless of how the nation performs, the Church of Jesus Christ, the covenant people of the Lord, need to pass the test!

I encourage us on this year’s Patriots’ Day and Day of Service and Remembrance to solemnly remember those we lost and to remember the lost, surreal post-9/11 national unity. We must do the hard work of unity in the Church, in our communities, and in the nation. We can serve one another, particularly those we disagree with. We can ask the questions Elder Renlund posed. “What can I do to foster unity? How can I respond to help this person draw closer to Christ? What can I do to lessen contention and to build a compassionate and caring Church community?”

And we can be patriots. As President James E. Faust said at the September 11, 2002 devotional:

We, as [American] citizens, are among the most favored of any of God’s children ever to live under any government on the earth. This is still true despite our country’s many challenges and difficulties. With all of these favored circumstances come the responsibilities and duties of citizenship. We should be participants, not merely bystanders, in the processes of democracy to ‘preserve us as a nation.’

We must choose to be the surreality that, to paraphrase Breton, resolves the contradictory conditions of the dream of Zion and the reality of human society. Let us choose to be surreal.

The post Reflections on 9/11: Why America’s Unity Didn’t Last appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →