Islam is an increasingly prominent force in the modern world, and it is often accused of being an inherently violent religion. The actions of terrorists who justify their actions through religious teachings are taken as representative of a deep and essential tie between Islam and violence. According to some, this violence shows that the core, central teachings of Islam, as given by both the Al-Quran and the prophet Muhammed, have an inescapably violent bent to them.

The idea of violent Islam fits into a persistent criticism of religion in general, which is that religious people and groups are unusually violent. Charles Kimball writes, “It is somewhat trite, but nevertheless sadly true, to say that more wars have been waged, more people killed, and these days more evil perpetrated in the name of religion than by any other institutional force in human history.” For example, recent Netflix series depicts Brigham Young, an early president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as a “villainous, violent fanatic,” despite evidence that Latter-day Saints were less violent than other groups at the time. The idea of violent Islam fits a persistent criticism, which is that religious people and groups are unusually violent.

All Muslims?

As a threshold matter, it’s hard to know what it would mean to say that Islam is inherently violent. If this is true, does that mean that every Muslim will unavoidably engage in violence? Or perhaps not everyone, but only 50%? 20%? 10%? 1%? Or perhaps something more ambiguous, such as that “wherever” we see Islam, we see political violence?

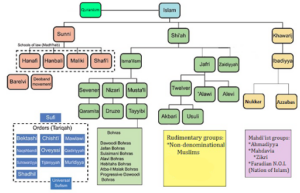

Further, when we speak of Islam, what are we referring to? It is critical to understand that there is no single understanding of Islam. There are myriad sects and movements within Islam, each with its own particular ideas and teachings. Here is a chart showing the basic divisions of Islam:

As with other major religions, these different branches within Islam do not always agree with each other on many core teachings and practices. Even within a particular branch, there can be many differing opinions from different leaders on specific concepts. Whenever extremist groups claim to be speaking for “Islam,” they clearly do not represent the views of millions of other Muslims.

The Reality of Violent Islam

Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that a great deal of violence has been perpetrated by self-identified Muslims and that such violence is often justified in religious terms. The most recent well-known event was the October 7, 2023, Hamas-led attack on Israel which killed 1,139 Israelis and others and injured thousands. Many Americans have vivid memories of the September 11, 2001, Twin Towers attacks, which killed 2,977 people. As of 2015, four Islamic extremist groups (ISIS, Boko Haram, the Taliban, and al-Qaeda) were responsible for 74% of all deaths from terrorism. From 2011 – 2019, there were between 13,000 and 33,000 deaths per year from terrorist attacks. Most of these attacks and deaths have been in Muslim-majority countries. One study claims that over 167,000 people have been killed by Islamist attacks over 40 years; 90% of those victims were other Muslims.

It is also true that Islamic extremist groups often justify their attacks using their religion, specifically their interpretations of Islamic texts such as the Quran, the hadith, and Sharia law. Their reasoning includes armed jihad as retribution for perceived injustices against Muslims by non-believers; the belief that certain self-identified Muslims have violated Islamic principles and are therefore considered disbelievers (takfir); the perceived obligation to restore Islam’s dominance by implementing sharia law and reestablishing the Caliphate as a unified Islamic state (e.g., ISIS); the pursuit of heavenly rewards through martyrdom; and the conviction that Islam is superior to all other religions. Extremist groups often justify their attacks using their religion, specifically their interpretations.

It is difficult to find accurate estimates of how many Islamic terrorists there are in the world due to the clandestine nature of these groups and the different definitions of terrorism. However, estimates have been made. In 2014, ISIS was thought to have at most 30,000 fighters in Iraq and Syria, plus another 30,000 from other countries. There are about 10,000 fighters detained in Syria as of 2024. Al-Qaeda and the Taliban potentially have tens of thousands each. When all the terrorist groups are put together, most sources seem to estimate there could be around 100,000 individuals. The highest number I found was from a report in 2018 that estimated there were up to 230,000 Salafi-jihadist and allied fighters worldwide. In comparison, the global Muslim population is 1.9 billion. Thus, the highest estimates of Islamic terrorism posit that .005% to .012% of all Muslims are terrorists. In other words, 99.99% of Muslims in the world are explicitly not terrorists.

Violent Verses in the Quran

Despite looking at these numbers, some may still say that the actual Al-Quran preaches violence. Specific Quranic verses certainly seem to condone violence, such as the “Sword Verse”:

“… kill the polytheists who violated their treaties wherever you find them, capture them, besiege them, and lie in wait for them on every way” (Surah At-Tawbah 9:5).

Critics claim that such verses are evidence of Islam’s endorsement of violence. There are three reasons why pointing to violent verses in the Quran as evidence for Islam’s fundamental violent nature is not a particularly convincing argument.

First, like many religious texts, I suspect that these verses are often taken out of context by both critics of Islam and violent Muslims themselves, trying to religiously justify their actions. There are many people who perpetuate evil in religious and non-religious contexts. People with evil intentions will find justifications for their actions if they look for them. The Al-Quran is certainly not the only holy text used as justification for horrendous acts.

Second, if one is going to accept the Al-Quran as an authoritative voice when it comes to violence, then one must accept the whole Al-Quran. There are other verses that preach peace rather than violence:

“… Whoever takes a life … it will be as if they killed all of humanity; and whoever saves a life, it will be as if they saved all of humanity” (Surah Al-Ma-idah 5:32).

“Good and evil cannot be equal. Respond to evil with what is best, then the one you are in a feud with will be like a close friend” (Surah Fussilat 41:34).

“The true servants of the Most Compassionate are those who walk on the earth humbly, and when the foolish address them improperly, they only respond with peace” (Surah Al-Furqan 25:63).

The meaning of particular verses is situated by the overall meaning of the text. While I may not be an expert on the Al-Quran, Christians and other believers (and non-believers) should be able to understand that certain passages can be selectively employed in a way that goes against the overarching message of the text. Religious texts across traditions contain violent passages, yet they are not deemed inherently violent.

The Concept of Jihad

Beyond specific Quranic verses, the concept of jihad offers a clear example of how Islamic doctrine can be subject to widely varying interpretations. Critics and Islamic extremists often claim that jihad primarily means “holy war” and use it to justify violence against non-believers by presenting it as a divine mandate for conquest. However, many Islamic scholars and practitioners interpret jihad differently by viewing it primarily as a personal, spiritual struggle to live a righteous life and resist evil—much like the Christian exhortation to “put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the schemes of the devil” (Ephesians 6:10-11).

Armed jihad is still considered a significant concept in mainstream Islamic teaching, but it is thought of as secondary and limited to defensive contexts. Thus, as with many religious teachings, the meaning of jihad depends on interpretation and context. The existence of peaceful, alternative interpretations within Islam demonstrates that the Quran, like any religious text, offers a range of possible readings. That flexibility itself suggests that Islam cannot be reduced to a singular, violent doctrine.

It is also worth pointing out that most victims of extremist violence are Muslims. In other words, the violence mostly comes from some Islamic sects against other Islamic sects, highlighting that the violent sects do not necessarily represent Islam itself, nor do they primarily target non-Islamic populations. Extremist groups often represent fringe interpretations that are condemned by most other Muslims. The vast majority of Muslims simply don’t belong to terrorist sects of Islam.

Potential Origins of the Call to Violence

While extremist groups and their actions are often cited as evidence of Islam’s supposed inherent violence, a closer look reveals that their motivations and justifications are often far more political than theological. In fact, many of these groups and the regimes they represent leverage religion as a tool to consolidate power, often distorting Islamic teachings to suit their ambitions.

While there are Islamic terrorist groups in many places around the world, the majority of them are concentrated in a few countries of the Middle East. Often these groups aren’t just operating within a country’s borders, they are running the country. The Taliban regained control of Afghanistan in 2021, Pakistan has housed various Islamic terrorist groups, and ISIS stands for Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. These governments are run by people who have shown they will leverage religious authority and their people’s faith for their own violent ends. Extremist groups’ motivations and justifications are often far more political than theological.

Personal and Observational Evidence

The most compelling evidence for me as to why I don’t think Islam is fundamentally violent comes from personal experience. It’s not official, it’s not professional, it’s not scientific, but I do think it is relevant.

I served a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Indonesia, which is the country with the largest Muslim population in the world. For two years, I lived alongside 235 million Muslims, at least 87% of the nation’s total population. I talked with, walked with, ate with, and lived with Muslims every single day for two years in Indonesia. Not one of them tried to kill me. None of them assaulted me. None of them even gave me a little push or yelled at me to get out of their country. In fact, the only people who kicked me out of their house for teaching about Jesus Christ were other Christians.

During my time there, Indonesian Muslims would frequently and emphatically disavow terrorist groups, insisting “they are not really Muslim.” These weren’t casual statements made in passing—they were heartfelt declarations from people who were deeply troubled by how their faith was being misrepresented by extremists. Despite being a visible religious minority as a Christian missionary in a Muslim-majority country, I never once felt physically threatened or in danger. Insisting that your Muslim neighbor’s faith requires violence is not a good foundation for friendly relations.

Looking Forward

I have yet to be convinced that Islam is an inherently violent religion. The bigger question for me is, how do we live with our Muslim neighbors? How do we, as a country, a society, a world, and a people live with others who have a radically different worldview than us? Well, that’s always been the question. How do people with irreconcilable differences get along? I have no idea, but for what it’s worth, I don’t think the differences are as big and daunting as they might seem. Every religion and worldview has some sharp edges that need to be smoothed down, edges that come more from culture and history rather than doctrine and teachings.

One thing is certain: insisting that your Muslim neighbor’s faith requires violence is not a good foundation for friendly relations. Claiming all Muslims are disposed to violence because of their religion is a gross and misleading generalization. As the Muslim and Western worlds increasingly come into contact with each other, we have choices about how we will interact. Refraining from tarring all Muslims as violent is a crucial first step toward building better relationships with our Muslim neighbors.

The post Beyond the Sword: Challenging the Myth of Islam’s “Inherent” Violence appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →