Download Print-Friendly Version

Download Print-Friendly Version

There is a strange word at the center of the Hebrew Bible. A word so often translated as “God,” even though, quite literally, it means “gods.” A word that carries the weight of centuries, even though its form is suspiciously plural. That word is Elohim. At first glance, it sounds simple. Just a name for God. But names, especially in scripture, are never just names. They are mirrors of meaning, and Elohim reflects something more complicated than it lets on. It is a plural noun, the kind one would expect to describe a pantheon. And yet, nearly every time it appears, it points to just one being (Gesenius, §124g; see also Waltke & O’Connor, §7.4.3b).

So why did a people so famously committed to monotheism choose a word that so clearly belonged to the world of many gods? That question has never stopped echoing. Scholars have tried to make it neat. Some call it a grammatical flourish, a kind of plural of majesty (Ibid). Others say it is a relic from before the line between one God and many was drawn (Smith, p. 32–49). Still others suggest something bolder. That Elohim holds a memory, half-erased, of divine duality. A definition that includes both male and female (Barker, pp. 39–65). This essay builds on those frameworks using a Latter-day Saint hermeneutic of restoration, approaching linguistic remnants like Elohim not only as historical curiosities but as echoes of a divine family structure. A word that carries the weight of centuries, even though its form is suspiciously plural. That word is Elohim.

The Shape of the Word

So what do we do with a word that ends in “im”—the Hebrew marker for plural masculines—and yet behaves as if it were singular? It is tempting to wave it off. To call Elohim a quirk of ancient grammar. Some words, like mayim for water or shamayim for sky, are plural in form but singular in meaning. Maybe Elohim is one of those (Gesenius, §124g; see also Waltke & O’Connor, §7.4.3b). That would make a tidy explanation, and it has often been used to support later Christian ideas like the Trinity. But the ancient authors weren’t Trinitarians. That concept wouldn’t emerge for centuries. If this were truly a case of singularity hidden inside plurality, we would expect consistency across Hebrew scripture. Instead, what we see are moments that speak of more than one, distinct in person, unified in action.

The word Elohim begins with El, the Semitic root for “god.” It’s seen everywhere—Hebrew, Ugaritic, Akkadian (Cross, pp. 7-15). A simple root, just two or three letters, became the definition of the divine. While Elim (e.g., Exodus 15:11) represents the regular morphological plural of El, the form Elohim, derived from Eloah, emerges as the dominant theological term, perhaps precisely because its structure encodes a deeper multiplicity. That is the pattern found with malachim (angels) and seraphim (seraphs). Clean. Predictable. Elohim, though, breaks the mold. It adds an unexpected vowel, a long “o.” And that “o” doesn’t fit the normal plural rules. Scholars have proposed different explanations. Some suggest Ugaritic influence, others point to the singular form Eloah, a word that ends with “ah,” the same feminine suffix found in Torah and Shekhinah (Frymer-Kensky, pp. 20–27). A masculine plural built from a feminine root (Smith, p. 45). A linguistic hybrid.

Which means Elohim might just mean more than “gods.” In linguistics, we call this etymological layering. A memory held in the shape of a word. A blending of divine gender. A grammar with theological consequences (Smith, ch. 3). This becomes clearer when looking at the verbs. In the Hebrew Bible, Elohim takes singular verbs. Elohim created, Elohim spoke, Elohim called (Genesis 1:1; Exodus 6:2; Deuteronomy 5:6). As if the word wants to sound plural, but act singular. Or maybe contains both.

That tension didn’t go unnoticed. Wilhelm Gesenius called it a plural of majesty, a way of signaling fullness, not number (Gesenius, §124g; see also Waltke & O’Connor, §7.4.3b). Like mayim doesn’t mean many waters. Or shamayim doesn’t mean multiple skies. Perhaps Elohim isn’t meant to count. It’s meant to encompass. Still, that explanation only goes so far. Because Elohim isn’t just an abstract noun. It carries memory. There are places in the Hebrew Bible where the plural leaks through. Places where the verbs stop agreeing. Where Elohim behaves like a “they.” The language doesn’t forget what it used to mean. Elohim might just mean more than “gods.” In linguistics, we call this etymological layering. A memory held in the shape of a word. A blending of divine gender.

It is not just a name. It is the record of a transition. From a world of gods to a theology of one God. From a divine family to a single throne. From “they” to “He.” But the language still remembers.

A Word Shared Among the Gods

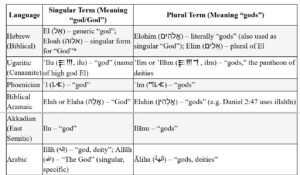

To really understand the mystery of Elohim, Israel has to be left behind. For a moment, step out of Jerusalem and look to its neighbors. Ugarit. Phoenicia. Babylon. In those ancient languages, the names for God form a pattern, a family of sounds, of roots, of divine names that speak to something older and broader than a single theology. When we line up the terms for “god” and “gods” across related Semitic languages, the shared grammar and divine plurality become hard to ignore, as shown in the table below (Smith, pp. 41-45, and Cross, pp. 13-15).

Table 1: Terms for “God” in Various Semitic Languages

For Latter-day Saints, this sounds familiar. Joseph Smith restored a vision not of a lonely God, but of a divine council—a family of heavenly beings who stood in order, with purpose (see Doctrine and Covenants 121:32, and Abraham 3:22–26). He wasn’t inventing this. He was restoring something that had been remembered dimly and had been written out sharply.

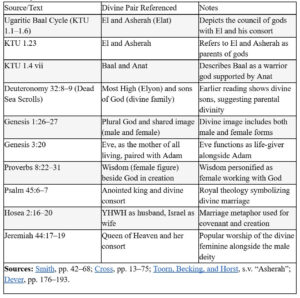

The restoration by Joseph Smith didn’t return to the theology of the Second Temple period. It reached back farther, before the edits, before the reforms of Josiah, before the sacred feminine was silenced. He didn’t restore monotheism; he restored the Father co-presiding with the Mother and their only begotten son Jesus Christ. Back to the First Temple age, when the divine family still stood intact. It can be seen in the shape of Ugarit. The high god was El. His consort was Asherah. Together they bore seventy children, each assigned a nation to rule (Smith, pp. 41-55). This divine pairing is further corroborated by archaeological finds such as the inscriptions from Kuntillet ʿAjrud, which reference “Yahweh and his Asherah”. They are a tangible witness to the male and female divine dyad present in early Israelite religion (Meshel, pp. 20–23). The Divine Pair, Their son, and that number, seventy, would echo into the Bible. So would the structure.

In Deuteronomy 32, there is a telling change. The original Hebrew said the nations were divided “according to the sons of God.” But later scribes changed it. While the Hebrew Bible doesn’t explicitly name Yahweh as the son of El, the linguistic structure and surrounding traditions (including Deut 32:8’s earliest versions) suggest a divine hierarchy that resonates with Latter-day Saint cosmology (Smith, p. 33; see also Joshua 22:22). The Masoretic text now reads “sons of Israel” (Tov, pp. 115–117). The Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls preserve the earlier version—which means at some point, someone made a choice. They erased the divine family and replaced it with a national God.

Joseph Smith called that kind of editing a loss. An intentional erasure of heaven’s order from the record of earth. And his work recovered theology and restored memory. The divine family, Father, Mother, and their children, was the structure from the beginning (Smith, pp. 370–371). Hear the echoes across the Semitic world as shown in the table below. In Phoenician: ʾl and ʾlm. In Aramaic: Elah and Elahin. In Arabic: Ilah and Aliha. Even in the Qur’an, plural pronouns appear when God speaks. These are linguistic fossils teaching the lost truth from the beginning (Sáenz-Badillos, pp. 33–38). Elohim belonged to a time when divine plurality was the norm. Later rulers reframed it. “Who is like you among the gods, O Yahweh?” That line from Exodus demonstrates the existence of other gods. It asserts Yahweh’s supremacy among them (see Exodus 15:11; also Psalm 82). In the Latter-day Saint view, this fits beautifully. Jesus Christ, as Yahweh, stands above all the elohim, the spirit, children of God, as the Firstborn. The one appointed. Above him are the Eternal Father and Mother. We find ourselves below Him, as the children. The elohim He rules over are us.

Table: Scriptural and Archaeological Evidence for Male–Female Divine Pairs in Ugaritic and Early Israelite Traditions

It’s a stunning structure—one title, three identities. First, the Heavenly Parents. Second, Yahweh the Son. Third, the divine children, still becoming. This theology is a name that tells a story. A family name, layered and alive (Givens, pp. 61-65).

When One God Speaks in the Grammar of Many

It’s one thing for a word to be plural in form. It’s another for it to behave that way. Most of the time, Elohim acts singular. The verbs align. Created. Spoke. Called. It follows the grammar of one. But every so often, the mask slips. Genesis 1:26 is one of those moments: “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” The verbs shift. The pronouns are plural. Genesis 5 repeats the pattern: “Male and female created they them, and blessed them, and called their name Adam.” The creation of humanity was not a solo act. It was shared.

It is seen again in Genesis 20:13. Abraham speaks of Elohim causing him to wander, but the verb is hitʿu, plural. Not “he caused,” but “they caused.” And in Genesis 35:7, Jacob builds an altar because Elohim revealed themselves to him. The verb is niglu—they appeared. The grammar tells a different story. A divine duo. These are not mistakes. Ancient Hebrew doesn’t slip like that by accident. The moments when Elohim takes plural verbs happen at narrative peaks. Abraham’s exile. Jacob’s altar. These are moments when the veil thins and the plurality breaks through.

Joseph Smith had these patterns revealed to him. He taught that the divine was not a lone God. Heaven, he said, was organized. A Father and a Mother. A Son and their children (Smith, pp. 370–371). Modern readers may miss the duality because Hebrew doesn’t have a grammatical dual for verbs. But Arabic does. And in the Qur’an, God speaks in the dual. We created. We revealed. Not many gods. A unified two (Neuwirth, pp. 222–224). Angelika Neuwirth discusses divine plurality in Qur’anic grammar, noting that the use of the plural or dual forms such as khalaqna (“We created”) and anzalna (“We revealed”) reflects a liturgical and rhetorical convention with theological resonance. While not indicating polytheism, these forms suggest divine complexity and dual agency. There is more than just plurality hidden in the name Elohim. There is pattern. There is union. Some words hold their history in plain sight. Others bury it in form and sound. Elohim does both.

The Hebrew scriptures still carry these seams. In 2 Samuel 7:23, the verb halekhu, they went, is tied to Elohim. In Deuteronomy 5:26, the phrase Elohim ḥayyim, the living God, uses a plural form. In Psalm 58, Elohim is paired with shoftim, judges, again plural. These moments are rare, but they matter (Ricoeur, pp. 1-37). Over time, later translators tried to smooth it all out. The Septuagint uses ho theos, a clean, singular God. But Hebrew never quite cooperated. The verbs flicker. The nouns wobble. But the memory remains.

Elohim is not just a name. It is a record—a word that carries within it the echo of a divine council, a heavenly pair, and a family learning to become (Barker, pp. 26–45).

The Marriage Hidden in the Name

There is more than just plurality hidden in the name Elohim. There is pattern. There is union. Some words hold their history in plain sight. Others bury it in form and sound. Elohim does both. It looks masculine and plural, but it carries inside it a feminine root, Eloah. That kind of linguistic pairing happens when language remembers something its speakers are starting to forget. And that something is marriage.

In the ancient world, divinity was often imagined as a pair. El and Elat. Baal and Asherah. Heaven and Earth. These are active agents, joined in purpose, distinct in role. Latter-day Saints have a phrase for this: eternal companions. The idea that divinity exists in relationship. That God’s image is found in the union. The scriptures hint at this again and again. Genesis 1:27 says that humankind was created in God’s image, male and female. Not separately, but together. That is the pattern. Not uniformity, but complement. Not hierarchy, but balance.

Most traditional theology stops short of calling God both male and female. It names God above gender or beyond it. But the restored gospel gives a different lens. Joseph Smith taught that there is no God without the union of a male and a female (Snow, Discourse 26). That is the structure. A relationship. Not sameness. Not collapse. But difference, bound in covenant. That is what Elohim preserves. A name that holds both halves of heaven. It is modeled in temple worship, reflected in scripture, and confirmed in prophetic teaching. The idea that male and female together form the divine image is the restoration (Doctrine and Covenants 132:19–20; Moses 2:27).

You can hear it in the resonance of the name. You can see it in the grammar. And once you notice the pattern, it shows up everywhere. A text refusing to let theology forget what it once knew.

The post The Divine Echo: What the Word ‘Elohim’ Still Remembers appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →