The reality is that we know very little with certainty about what the facsimiles in the Book of Abraham originally were or why they were considered significant in the ancient world. While scholars can identify the general type of Egyptian artwork they resemble, there is far more uncertainty surrounding who originally used them, how they were understood, and what purpose they served.

We do not know exactly who created the papyri Joseph Smith possessed, how the images were interpreted at different times, or how those meanings may have changed across centuries of copying and reuse by different people with different beliefs.

Because so much is unknown, saying the facsimiles can only mean one thing assumes too much. It treats one interpretation as the only possible option and ignores other reasonable explanations, which is a false dichotomy logical fallacy.

Egyptians Understood Counterfeit Interpretation

It is very difficult to understand ancient Egyptian culture, their priorities, and what their symbolic meanings were intended to convey. In addition, symbols usually have multiple meanings and layers of meaning.

According to Book of Abraham 1:27, the Egyptians did not have the priesthood, but Pharaoh was a righteous king who attempted to mimic the true ordinances that had been practiced by Adam and the ancients. Because of this, their worship appears to have been an attempt to tell the story of Adam, the Creation, and temple ordinances without proper authority. Their religion and practice of worshiping many gods came through a corrupted, counterfeit perspective that was very different from the way Adam and Abraham were taught.

When interpreting the facsimiles through the lens of an Egyptian belief system centered on false gods, it becomes difficult to see them the same way Joseph Smith did. Joseph Smith was interpreting the facsimiles as a restoration of the original meaning held by the ancients.

Joseph Smith’s explanations reflect the correct understanding that Abraham had of these truths, even if the Egyptians themselves only partially understood what they were trying to preserve.

Understanding What the Book of Abraham Facsimiles Are

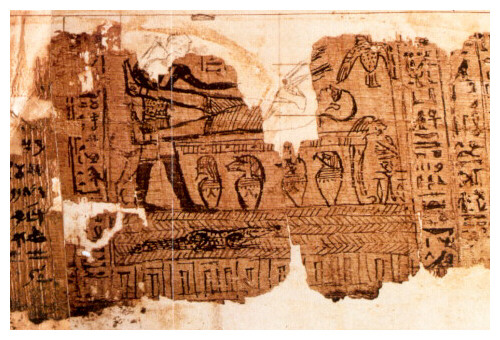

The Book of Abraham facsimiles are printed images taken from Egyptian papyri that Joseph Smith obtained in 1835. These images were published in the Times and Seasons in 1842 and later included with the Book of Abraham in the Pearl of Great Price. The facsimiles also include brief explanations that scholars believe, though not absolutely certain, were provided by Joseph Smith.

These images are now commonly referred to as Facsimile 1, Facsimile 2, and Facsimile 3.

At a basic level, it is fairly clear that the facsimiles are examples of Egyptian imagery, art, and symbolism that likely date to around 200 BC. What they mean, how old their source material truly is, and how they were understood anciently make understanding these documents far more difficult to determine.

Assumption That Other Facsimiles Have Same Origin

Facsimile 1 is the only facsimile for which a portion of the original papyrus has survived. Egyptologists have identified that this papyrus comes from a funerary context and includes the name of an Egyptian priest named Hor. Some of the surviving papyri were likely prepared for Hor’s burial, but we do not know with certainty which mummy, if any, belonged to him.

Michael Chandler brought multiple mummies and multiple papyrus fragments and scrolls. Originally he had eleven mummies in total. We cannot say with certainty which papyri were originally associated with which mummies, or whether all the papyri Joseph Smith worked with belonged to Hor’s funerary collection. It is possible that some of the scrolls or images referenced by Joseph Smith came from different sources.

Published Images Were Modified

The images we have today are not direct reproductions of intact ancient documents. The papyri were already damaged by the time Joseph Smith acquired them. In Facsimile 1, portions of the papyrus were missing, including parts of the figures.

Since that time, even more of the papyrus has been lost or decomposed, as parts of the original images had been pasted onto backing material. After more than 150 years without proper storage, additional portions of this fragment have disintegrated compared to what Joseph Smith had in 1835.

Facsimile 2, a circular hypocephalus, was also incomplete, with sections broken away or unreadable, especially on the right side of the document labeled as figures 12–15. Because of this, when the facsimiles were prepared for publication, artists reconstructed missing portions of the image by relying on common Egyptian artistic patterns and symmetry. These reconstructions represent educated guesses, not confirmed restorations of the original artwork.

The reproduction process added further distance from the ancient source. The papyri were first copied by hand, then redrawn by artists, and finally engraved onto metal plates for printing in the Times and Seasons.

The artists and engravers involved were not trained in the Egyptian language or hieroglyphics. Their goal was visual reproduction, not linguistic accuracy. As a result, some hieroglyphs and symbols were altered, simplified, reversed, or distorted during the transfer from papyrus to drawing to engraved plate.

This means the facsimiles printed in modern scriptures are several steps removed from the original ancient images. They reflect damaged source material, reconstructed sections, and nineteenth-century artistic interpretation layered on top of ancient drawings. Because of this, precise claims about the original appearance, wording, or intended meaning of every symbol cannot be made with certainty.

What We Actually Have

The Age of the Existing Papyrus

The papyrus connected to the Book of Abraham facsimiles that still exists today dates to around 200 BC. This means it was created long after Abraham lived. It is not an original document from Abraham’s time, but likely a copy of a copy of much older material. Along the way, variations may have been introduced, including changes to names or how figures were understood, reflecting the beliefs of the time in which each copy was made.

A World of Greek and Jewish Influence

By 200 BC, Egypt was no longer an independent Egyptian kingdom. It was ruled by Greek leaders following the conquests of Alexander the Great. Greek officials controlled the government, Greek was widely spoken, and Greek ideas influenced education, science, and religion.

At the same time, Egypt had a large Jewish population. Many Jews had lived there for generations. Jewish scriptures were being translated into Greek, and Jewish stories and beliefs were well known in cities like Alexandria and Thebes. Abraham, Moses, and the God of Israel were not obscure figures in this world.

Because of this, Egyptian religion during this period was not isolated. Egyptian priests lived in a mixed cultural environment shaped by Greek philosophy and Jewish religious ideas. As Dr. Kerry Muhlestein explains in Let’s Talk About the Book of Abraham, priests during this period often reused older religious images, gave them new meanings, combined Egyptian ideas with foreign ones, and collected names and stories from different religious traditions.

Why Meaning Is Difficult to Fix

We know this cultural blending occurred because Egyptian texts from this period sometimes include Jewish names and concepts mixed into Egyptian religious practices.

So when we look at the papyrus owned by Hor, we are not looking at something created in a pure or original Egyptian setting. We are looking at a document produced in a mixed cultural world where meanings had already shifted.

An image that once meant one thing centuries earlier might now carry a different meaning, or even multiple meanings at the same time. Symbols were flexible and were meant to communicate ideas rather than lock meaning into a single, fixed definition.

This is why modern scholars cannot say with certainty what every image was meant to represent. People living in different times and cultures would have understood the same image in different ways.

The papyrus we have comes from a world where cultures overlapped, religions mixed, and symbols changed meaning over time. This makes it very difficult, and often impossible, to claim that there is only one correct interpretation of the facsimiles.

Copies Do Not Equal Origins

Egyptian Religious Images Changed Over Time

Ancient Egypt lasted for more than three thousand years. During that time, religious images and texts were not treated like fixed museum pieces. They were copied, reused, adapted, and given new meanings in different places and different centuries.

The way Egyptians handled religious material means we should not expect symbols to have one permanent, unchanging meaning across all periods of Egyptian history.

What We Can and Cannot Date

We do have surviving papyrus connected to Facsimile 1 from the Joseph Smith Papyri, and Egyptologists date it to the late Ptolemaic period, around 200 BC. However, we do not have the original papyrus sources for Facsimiles 2 and 3 in the same way. Because of that, we cannot say with certainty when their specific source documents were created, who first produced them, or the exact setting they were originally prepared for.

People assume that Facsimiles 2 and 3 must date to the same time period as Facsimile 1 because they were published together and came into Joseph Smith’s collection at the same time in 1835. That is a reasonable assumption, but treating this as fact can lead to conclusions that sound confident but rest on uncertain ground. The safest approach is to separate what can be dated and verified from what can only be inferred.

Copies, Adaptations, and Older Sources

Egyptian priests regularly copied older material onto new papyri, reused imagery for new purposes, layered new meanings onto existing symbols, and adapted religious ideas from earlier periods.

Because of this, a late copy does not rule out an earlier source. If Abraham lived around 2000–2100 BC, then a papyrus from 200 BC could only be a copy of something older, an adaptation of older ideas, or a reuse of imagery whose original meaning had already shifted.

Even if Abraham produced the facsimiles originally, it would be historically unrealistic that those documents would have survived for so long.

The Lens of the Later Owner

The surviving papyrus connected to Facsimile 1 appears to have belonged to the Egyptian priest Hor. That alone tells us something important about how the images should be understood.

Whatever the original meaning of the imagery may have been centuries earlier, what we have today is filtered through:

- the religious worldview of Hor

- the practices of the late Egyptian priesthood

- the multicultural environment of Ptolemaic Egypt

Meaning Was Not Fixed

By this period, Egyptian religion had already absorbed Greek, Jewish, and other Near Eastern influences. Religious meaning was not fixed or frozen in time. Symbols were reused, adapted, and reinterpreted as they were copied into new settings.

So even if a scene or concept originally came from a much earlier period, the version we have today may not reflect it exactly as it was first created.

We Do Not Fully Understand the Facsimiles

Modern Egyptology does not have a single agreed-upon interpretation of these images, a complete understanding of how they were used around 200 BC, or certainty about how different groups understood them. Scholars regularly disagree on details, functions, and meanings, even within the same time period.

Egyptian religious symbols were intentionally flexible. The same image could carry different meanings depending on the time period, the religious or cultural setting, the audience viewing it, and the purpose for which it was used. This is not speculation. It is a basic and well-documented feature of Egyptian symbolic religion, where imagery was designed to teach ideas rather than lock meaning into one fixed definition.

Because of this, insisting that the facsimiles can only have one correct interpretation reflects a misunderstanding of how Egyptian symbols were used and understood.

Joseph Smith’s Explanations and the Limits of Criticism

Critics assume that Joseph Smith attempted to produce a strict, one-to-one Egyptological translation of the facsimiles. The historical record does not support that assumption.

Joseph Smith did not present his explanations as a grammatical translation in the academic sense. He gave explanations of the images, not a line-by-line decoding of Egyptian text as Egyptology would later define it. His meanings, like almost everything he did, was designed to provide a spiritual explanation that would better help us understand the plan of salvation so that we can return to the presence of the Father through Jesus Christ.

What is clear is how Joseph Smith used the images. He connected them to ideas about the stars, divine authority, God’s order of creation, life, and sacred ordinances, using Abraham’s experiences as the framework for understanding them.

These explanations were published in 1842, at the same time Joseph Smith was beginning to introduce the Nauvoo Temple endowment.

Scholarly Disagreement Among Meaning Today

The fact that modern Egyptologists debate these images also does not demonstrate that Joseph Smith was wrong. It shows that the subject itself is complex and that definitive conclusions are difficult, even with greater understanding and modern tools.

The many disagreement among different scholars demonstrates the nature of Egyptian symbolism, and how there is not just one interpretation.

Ancient Ideas, Divine Order

Whether the original Egyptian artists intended these images to function as temple worship in the same way Joseph later taught cannot be stated with certainty.

What can be said is that Joseph Smith used the facsimiles to show that covenants, progression, and movement through a divine order were ancient concepts, not modern inventions.

Conclusion: TL/DR

The facsimiles in the Book of Abraham cannot be reduced to a single, fixed meaning. The original sources are fragmentary, the images passed through centuries of copying and reuse, and the cultural world in which the surviving papyri were produced was complex and mixed. Egyptian religious symbols were designed to be flexible, layered, and adaptable, not locked into one permanent interpretation.

Because of this, confident claims that the facsimiles can only mean one thing go beyond what the evidence allows. They rely on assumptions about origin, function, and meaning that cannot be proven and ignore how Egyptian religion worked. Modern Egyptology itself does not speak with one voice on these images, which demonstrates how difficult definitive conclusions really are.

Joseph Smith did not claim to provide a modern academic translation of Egyptian grammar. He offered explanations that framed the images within Abraham’s experiences and used them to teach ideas about divine authority, the order of creation, the stars, covenants, and sacred ordinances.

Given the fragmentary evidence, the shifting meanings of symbols over time, and the lack of certainty surrounding the facsimiles’ original purpose, it is not historically sound to dismiss Joseph Smith’s explanations outright.

The facsimiles remain far more complex and unresolved than critics acknowledge. When viewed in their full historical and cultural context, the Book of Abraham presents a coherent ancient framework that is impossible to explain as a made up nineteenth-century invention.

Understanding What The Book of Abraham Facimilies Are

Book of Abraham – Evidence Joseph Smith Could Not Have Known

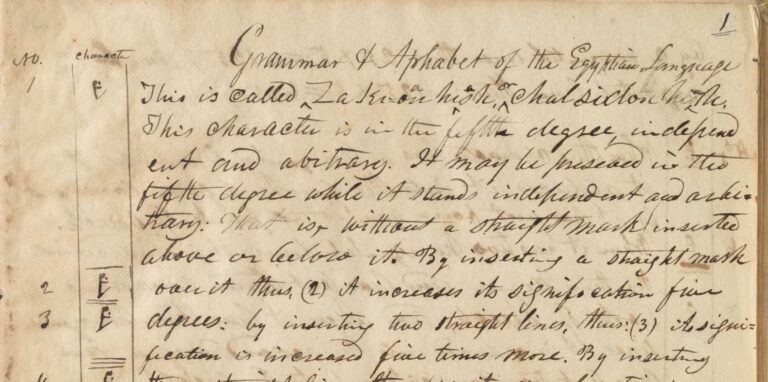

The GAEL Project – Pre-Temple Doctrine Coding?

Doctrine of the Book of Abraham

What is the Book of Abraham?

Continue reading at the original source →