As I was researching for the posts on the ankh, I came across some information which was interesting, describing the Egyptian concept of “time” and “eternity.” These concepts almost seem repetitive and redundant to our modern way of thinking, but to the Egyptians each of these terms represented something concrete and distinct, and both were invoked in certain rituals, texts, and illustrations. It is clear that the Egyptians considered these two ideas as unique, but they often used them together, and so it seems difficult for our present Egyptologists to distinguish or disambiguate what the Egyptians meant by them individually. There has been plenty of speculation.

As I was researching for the posts on the ankh, I came across some information which was interesting, describing the Egyptian concept of “time” and “eternity.” These concepts almost seem repetitive and redundant to our modern way of thinking, but to the Egyptians each of these terms represented something concrete and distinct, and both were invoked in certain rituals, texts, and illustrations. It is clear that the Egyptians considered these two ideas as unique, but they often used them together, and so it seems difficult for our present Egyptologists to distinguish or disambiguate what the Egyptians meant by them individually. There has been plenty of speculation.

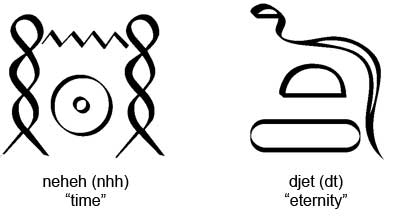

The two symbols used for the commonly translated “time” and “eternity” are neheh (nhh) and djet (dt), respectively, and looked something like this:

Jan Assmann described the difficulty of pinning down an understanding of these hieroglyphics:

The meaning of this disjunctive concept of time and its two components cannot be translated by any pair of words in Western languages. The Egyptian terms in no way correspond to our “time” and “eternity”; this distinction deried from Greek ontology (eternity as the punctually concentrated presence of being, which unfolds in time as the process of becoming) was not only foreign to Egyptian thought, but even contrary to it. Neheh and djet both have properties of our “time,” as well as of our “eternity,” and as a practical matter, either can sometimes be translated as “time” and sometimes as “eternity.” The terms refer to the totality (as such, sacred and in a sense transcendent and thus “eternal”) of cosmic time. To clarify this concept of time and its religious implications or semantic range, we must heed an important distinction. We are so accustomed to the notion of infinity that we think of “totality” as finite and bounded. The Egyptians, however, viewed “totality” as the opposite of finite and bounded. To them, the boundaries of totality were not contrasted with the unbounded, but with the “whole,” with “plenitude.”1

As foreign as these concepts seem to Western and modern thought, Assmann proposes further understanding, going back to the Book of the Dead:

In chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead, a compendium of Egyptian mortuary beliefs in the form of a series of questions and answers (an initiate’s examination?), the expression “all being” is explained as “neheh and djet.” What this means is that neheh and djet designate the comprehensive and absolute horizon of totality. They refer to the temporal totality of the cosmos, but it was in this way that the concept of “cosmos” or “being,” that is, of reality, was comprehensible to Egyptian thought and capable of articulation. This totalization of being on the temporal level is so foreign to us that some scholars have proposed that djet and neheh mean “space” and “time.” This is not correct, however; both are unequivocally temporal concepts, and in Egyptian thought, they represented the whole of reality.2

So how are we to understand neheh and djet?

The closest we can come is a pair of concepts such as “change” and “completion/perfection” . . .

We can also illustrate the Egyptian disjunction of time with the help of the concepts “come” and “remain.” It is often said of neheh-time that it “comes”: it is time as an incessantly pulsating stream of days, months, seasons, and years. Djet-time, however, “remains,” “lasts,” and “endures.” It is the time in which we distinguish the completed, that which has been effected in the stream of neheh-time, which has matured into completion and has changed into a different form of time that will undergo no further change or motion.

The concept neheh can still best be connected with our everyday notion of time. For us, time is less something that comes than something that goes by, but in any case in motion. . . . djet signifies . . . the enduring continuation of that which, acting and changing, has been completed in time.3

Modern Kemeticism offers more explanation:

The term neheh refers to the cyclical nature of time as expressed in the passage of seasons and celestial events, the time that is not linear, but goes in a spiral with the repetition of certain events: day and night, seasons, holidays, and the natural cycles of life. Neheh’s cyclical nature can be observed in the hieroglyphs that make up its symbol, all of which are characterized by curves or non-linear surfaces: the top wavy line standing for water, the two hieroglyphs at each side that are the wick of oil lamps that burn in the night, and the circle with a point in the middle, universal symbol of Ra, the sun itself. . . .

This term, djet, specifically refers to the concept of linear, or nonrepetitive time, and this can be seen symbolically in its hieroglyphs: the long, linear snake of the dj sound, the flat loaf of bread which supplies the feminine t ending, and the long island symbol being the determinative for “land.” Thus, djet is earthly time, the time of the land.4

The sum of the two was always used to finish the ritual:

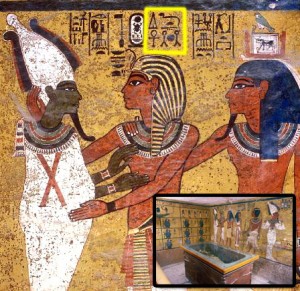

Djet and neheh are symmetrical concepts and are almost always used together, “eternity and everlastingness” in English, or perhaps the same as our idiomatic “forever and ever.” In ancient times, the act of ritual purification was shown with the gods pouring water jars containing the symbol ankh, or life, over the person being purified. A person was then said to be pure forever (djet) and ever (neheh), or in both manners of counting of time, both in years and in memory.((ibid. See the second part post on the ankh for a representation of this.))

So we begin to get this conceptualization of a time which belongs to this earth, and a time that belongs to the cosmos, or celestial events, equinoxes, the movement of the sun and stars, etc. Neheh is generational time and repeats, whereas djet is permanent and unchanging in eternity. The model of “one eternal round” illuminates both views, eternal repetition and permanence (cf. 1 Ne. 10:19, notice also the dual usage of “times of old” and “times to come”; Mosiah 3:5; Alma 7:20; Alma 37:12; D&C 3:2; D&C 35:1; D&C 39:22; D&C 72:3; D&C 132:7, 18-19). This also conveys the thought that the gods were capable of eternal change while still being unchanging, since both symbols were bestowed by them upon the kings and queens, the repitition of an enduring process ad infinitum. This perception of time does not have a place in Western thinking, but hearkens back to the ancients. Such an explanation of time seems perfectly in keeping with Abraham’s discourse on the multiplicity of time measurements in Abraham 3. More home runs for Joseph Smith.

Of course, Hugh Nibley also adds his thought-provoking voice to the conversation:

Otto avers that, while nhh conveys the idea of “unending recurrence of the same, the concept of becoming, something like our ‘development,’” dt denotes “ineradicable endurance,” a state of being established to last forever. Thomas Allen’s translation of the Book of the Dead supports this, rendering nhh as “endless occurrence” or “endless recurrence” and dt as “changelessness.” … while A. Bakir has the idea that “… nhh connotes the concept of infinity associated with time before the world … came into being,” while “dt refers to the other infinity … the time when the temporal world comes to an end” … Gardiner has much the same idea, i.e., that dt is “eternity in the past” and nhh “eternity in the future” [see 1 Nephi 10:19] . . . A clear distinction is made in Book of the Dead chapter 17: “Others . . . say that the things which have been made are Eternity (nhh), and the things which shall be made are Everlastingness (dt).” . . .

“The nhh-eternity thus designates the unceasing recurrence of the same, the endlessness of time.” He agrees with Thausing that nhh is divisible into years, while dt cannot be so divided. . . .

There is a general agreement that time as nhh has an end, being bound to the conditions and cycles of this world, whereas eternity as dt is something solid and final, written with the earth symbol, which denotes the ultimate in unshakable solidity. But everyone seems to feel the rightness of both making a distinction and of closely associating the two ideas to make sure that the ordinances shall be effective both “in time,” by whichever means we choose to measure it, and “thoughout all eternity,” which is not to be measured at all. This is the expression that closes all major ordinances . . .5

Post from: Temple Study - Sustaining and Defending the LDS (Mormon) Temple

Time and Eternity: An Egyptian Dualism

Notes:- Jan Assmann, The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press (2001), 74.

- ibid., 74.

- ibid., 75.

- http://daily.kemet.org/archives/archive-052003.html

- Hugh Nibley, The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment, 2nd ed., 228-32.

Related Posts

Continue reading at the original source →