The following are my notes from a lecture given by Professor Emanuel Tov as a part of the Biblical Studies Seminar at St Mary’s College, University of St Andrews. Emanuel Tov is a professor of Hebrew Bible at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He was one of the editors of the Hebrew University Bible Project, a member of the editorial board of the journal Dead Sea Discoveries, and was co-founder and chairman (1991-2000) of the Dead Sea Scrolls Foundation. From 1990-2009 he served as the Editor-in-Chief of the international Dead Sea Scrolls Publication Project, which during those years produced 32 volumes of the series Discoveries in the Judean Desert. He is now working as a member of the Academic Committee of the Orion Center for the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls at the Oxford Centre for Postgraduate Hebrew Studies.

LDS readers, if you don’t know already, should be pleased to hear that Professor Tov has been to BYU on a number of occasions and has worked with many BYU professors, including Donald Parry, Stephen Ricks, Dana Pike, Noel Reynolds, David Seeley, Andrew Skinner, Kent Brown, and others (those are all that I could remember him mentioning off the top of my head). Many of these have worked with him on the translation and publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) and on the Dead Sea Scrolls Electronic Library, a project that BYU produced in an effort to make the DSS available in an electronic format (now part of the Dead Sea Scrolls Electronic Reference Library of E. J. Brill Publishers (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2006)). Professor Tov indicated to me that he has greatly enjoyed working with these BYU professors and commented on their notable devotion to their Church.

Without further ado, here are my notes from his lecture on Thursday, April 15th, 2010. I would just add that these are my own personal notes and they do not necessarily represent Prof Tov’s comments in full nor his exact wording.

Introduction by University of St Andrews Professor Kristin de Troyer

…We owe the publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls to Emanuel Tov…

Professor Tov’s Lecture: The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible

We will be talking about the biblical Dead Sea Scrolls (found between 1947 and 1956) and about the Hebrew Bible.

We should know that our modern translations of the Bible are based on the Masoretic text — this is the text that is also used in synagogues and in scholarship. The Masoretic text, however, comes from medieval times — it is very late.

Therefore, all our commentaries are traditionally based on these late biblical manuscripts. Were we misleading the world? No, the Masoretic text was very good, but it was late.

We’ll go back now 60 years in scholarship, when the first scrolls were found. There were (eventually) fragments of 930 scrolls found near the Dead Sea. They are mostly non-biblical. About 1/4 are biblical.

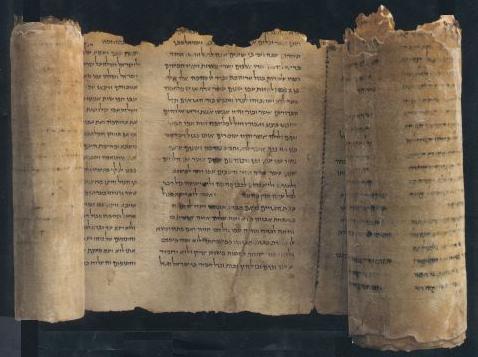

To cite some examples, the great Isaiah scroll was very complete; The scroll containing Chronicles, however, was only a very small fragment; the biblical scrolls found are of varying size.

(Commenting on the nature/appearance of the scrolls) They were sheets of leather sown together.

There were many scrolls found at Masadah — 23 biblical scrolls and many other non-biblical texts.

(Commenting on the people who formed the Qumran community) The keepers of DSS left the city and went to live a communal life in the desert.

Finding these scrolls of the Bible was a very great opportunity; for the first time we were able to see what this type of scroll looked like.

(On the nature of the biblical scrolls found) For example, 4QGenesis – the text of Genesis found on this scroll is exactly the same as the Masoretic text. The books of the Bible were found at Qumran in different quantities.

There were found 16 or 17 scrolls of Genesis.

- 14 or 15 of Exodus

- 36 of psalms (collections of psalms, but not full biblical Psalter)

- 20 of Isaiah

- only 1 of Chronicles

Everything around these scrolls is mysterious, we know nothing! There are as many theories as there are scholars. We know they are old — they are about 2000 years old. They date from around 250 BCE to about 70CE. It seems that the Qumran community liked the book of Deuteronomy, likely because of its preacher-like style, which the community tried to imitate. They liked the psalms because they must have used them for their daily prayers — they were used as a prayer book. There were many copies of the book of Isaiah, and it had much influence on the thinking of the people there.

Those that went to Qumran took phylacteries with them as well.

We get a good picture of what the biblical text looked like at that period. Among the scrolls we have found the square Hebrew script (Aramaic script) and also the older Paleo-Hebrew script (20+ examples). There is also a cryptic script — which was intended to give a “hidden” message from the leader to his followers. There were also some Greek and Aramaic fragments found. The Qumran community was living there for approximately 170 years.

There is no scroll of the “Bible” — nothing like a codex — it’s too early for that. There is one example of three books combined; or the minor prophets combined; but otherwise all books are separate.

4QDeuteronomy is a copy of Deut. 32, “The Song of Moses”– it has some very important content (which will be discussed later).

Some scrolls had only Psalm 119 alone (which means it was probably significant for them as well).

(Professor Tov begins commenting on the history of biblical texts)

It is hard to define what we mean by “original text” — it’s not necessarily what the prophet originally said (for example, if we had a recording of Jeremiah’s words which he spoke in the Temple), but we take into account the long history of how the text came to us.

As important as the DSS are, they are still removed by several stages from the earliest stages of the text.

When we talk about the Hebrew Bible, it is not just the text that we hold in our hands today. The text of the Bible is BOTH the text we hold in our hands (the Masoretic text) and also the other ancient texts that exist. The Masoretic text is the “received” text — from 250 BCE to today it hasn’t changed much. It already existed among the DSS, but was not the only version used there. At Masadah, we see the Masoretic text (really the proto-Masoretic text, because it was not yet vocalized). At Qumran, there was something very close to the Masoretic Text — and this is the largest group of texts. This was the proto-Rabbinic text.

There is a very small group of Hebrew texts at Qumran that is close to the Greek Septuagint (LXX). The LXX was produced around 280 BCE in Alexandria and Palestina (although we don’t often remember that it was also in Palestina). Some of the features of the LXX are reflected in these scrolls at Qumran.

The “Song of Moses” (Deut. 32) at Qumran has an extra line not found in the Masoretic Text — “Be happy with him you heavens and prostrate to him all you gods (sons of Elohim).” It speaks of more than one god — the “sons of God”. This is the same as the Greek text, but the line does not exist in the Masoretic Text. It was probably not included in the Masoretic Text because it was probably disturbing to some — for strict monotheists, it sounds very polytheistic. There are other places in the Masoretic Text (e.g. in some psalms) where this idea was not censored, but here it appears to have been. That is why the Masoretic Text is a shorter text here.

There is also, at Qumran, a shorter version of the Book of Jeremiah than what we have in the Masoretic Text. There are some Qumran texts that are close to the Samaritan Pentateuch as well. There are some texts that use a very different type of spelling from the Masoretic Text. There are other “non-aligned” (not similar to any known version) texts as well.

The Masoretic was a major text at Qumran (in quantities), but was not the only text — we need to look at all the texts in order to get the big picture.

Question and Answer Period

(Question regarding which biblical texts were found and when ? )

Answer: Check Discoveries of the Judean Desert, no. 39 — it gives a chronology of all the scrolls.

All the books of the Bible are there, except Esther.

(But that doesn’t mean that this was their “canon” of Holy Scripture) I haven’t mentioned Jubilees, Enoch, ben Sira, Temple Scroll (paraphrase of Deut.), etc. (other religious texts that are not included in our Bible). We do not know if these were part of their “canon” — we simply don’t know. They do quote Jubilees, Enoch, etc. in their own writings, so that may mean that they were considered authoritative. They probably used the familiar books of Hebrew Bible — plus others.

(Question from President Daryl Watson, LDS Stake President of the Dundee, Scotland Stake — Were there more polytheistic texts at Qumran than the one you mentioned?)

Answer: Yes, there were many more — look at Ps. 29:1, Job, etc. If you look at Anchor Bible Dictionary under “polytheism” or something similar, you should find an explanation of the situation at Qumran.

There were some ancient utterances that talked about plural gods, but these things were brushed aside in later biblical thought.

We can see that censorship is at work in our biblical text, that what we have is not the original form. A censor, maybe a Pharisee, censored these things out.

You could also see Bart Ehrman, for example, who shows that certain strains of Christianity censored the New Testament text for theological reasons.

Announcement by Prof Kristin de Troyer

There will now be an Emanuel Tov Scholarship at the University of St Andrews for PhD students doing text criticism of the Bible.

Continue reading at the original source →