Eich, Windsor, Memories Pizza, Obergefell. These are straws in the wind showing which way the wind is blowing. In fact, it has been clear for some time that the Mormon faith and the moral law were transitioning from –oddball and eccentric- to –wicked and despised-. The Church’s views on fornication, for example, have been at odds with the culture for some time. But our views were tolerable, just like our views on alcohol, or a vegan’s insistence on not eating meat. World War G and now World War T have ended that tolerance. We’re evil now. The blood libel is making an appearance .

How far this will go no one knows. What we may do may influence the outcome. Our enemies also get a vote and they are stronger than we. God also sets limits and bounds.

It’s not just Mormon Christians. It’s all of us who hold to the old moral law. Traditional Catholics, Orthodox, and Christians of all kinds. Some Jews. Perhaps some Muslims. Even those atheists whose eyes a bad fairy cursed at birth with the inability to see the Emperor’s new clothes. Basically, those of who follow the Tao, who believe that there is a Way.

The Chinese also speak of a great thing (the greatest thing) called the Tao. It is the reality beyond all predicates, the abyss that was before the Creator Himself. It is Nature, it is the Way, the Road. It is the Way in which the universe goes on, the Way in which things everlastingly emerge, stilly and tranquilly, into space and time. It is also the Way which every man should tread in imitation of that cosmic and supercosmic progression, conforming all activities to that great exemplar. ‘In ritual’, say the Analects, ‘it is harmony with Nature that is prized.’ The ancient Jews likewise praise the Law as being ‘true’. This conception in all its forms, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoic, Christian, and Oriental alike, I shall henceforth refer to for brevity simply as ‘the Tao’. Some of the accounts of it which I have quoted will seem, perhaps, to many of you merely quaint or even magical. But what is common to them all is something we cannot neglect. It is the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are. Those who know the Tao can hold that to call children delightful or old men venerable is not simply to record a psychological fact about our own parental or filial emotions at the moment, but to recognize a quality which demands a certain response from us whether we make it or not.

C.S. Lewis, from The Abolition of Man. In the West, almost all Taoists are Christians. But not all. Conversely, a great many nominally Christian institutions aren’t Taoists. They say, “the God that grants radical sexual autonomy, let Him be God.”

Of all the Taoist Christians, Rod Dreher has been at the forefront of exploring what we are to do.

He calls his explorations the Benedict Option.

But orthodox Christians must understand that things are going to get much more difficult for us. We are going to have to learn how to live as exiles in our own country. We are going to have to learn how to live with at least a mild form of persecution. And we are going to have to change the way we practice our faith and teach it to our children, to build resilient communities.

It is time for what I call the Benedict Option. In his 1982 book After Virtue, the eminent philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre likened the current age to the fall of ancient Rome. He pointed to Benedict of Nursia, a pious young Christian who left the chaos of Rome to go to the woods to pray, as an example for us. We who want to live by the traditional virtues, MacIntyre said, have to pioneer new ways of doing so in community. We await, he said “a new — and doubtless very different — St. Benedict.”

Throughout the early Middle Ages, Benedict’s communities formed monasteries, and kept the light of faith burning through the surrounding cultural darkness. Eventually, the Benedictine monks helped refound civilization.

I believe that orthodox Christians today are called to be those new and very different St. Benedicts. How do we take the Benedict Option, and build resilient communities within our condition of internal exile, and under increasingly hostile conditions? I don’t know.

The Benedict Option isn’t really a plan. Dreher is still groping after a plan. What he has is a clear-eyed recognition that the culture war is lost and we now have to find a way to keep faith in defeat.

This post is a response to the Benedict Option. It is the start of a long discussion. Expect many more posts on the subject. Guest posts from others are welcome, as are pointers to good outside sources. But as a starter, I am laying out here some historical parallels and important questions. The key points are bolded and italicized.

Benedict Option

There is some merit to the idea of partly-withdrawn intentional communities, which is what monasteries were. We as the Church have been able to outsource a lot of our social economy to the broader culture. Now we have to pull back in. In such circumstances, intentional communities would reduce interaction and thus irritation with the broader culture, while at the same time providing social reinforcement and social services to those within. (They would also make missionary work harder. That’s a key question: how to carry on missionary work under the coming conditions? In partial amelioration, it’s probably true that most middle class professional types don’t use their opportunities for missionary work very much anyway.) Intentional communities would be especially helpful at first when experiments and variety can help sort out the best models. So the Benedict Option may be a way station to the Ghetto Option, the Millet Option, or the Amish Option. Monastic communities, many of which had lay families attached, may be a good institutional or legal model for forays into intentional communities.

But the historical situation of the monastics was greatly different from our own. It is true that the monastic communities had to preserve knowledge and value that the outside culture lacked. But monasticism was high status in the culture. It had already got going well before the barbarians took over. When they did, the barbarians themselves had political status but not cultural status, so the monasteries continued to maintain their elite position at least culturally. Usually politically too, since the new conquerors usually found it politic to conciliate these institutions. When St. Benedict founded his particular Rule, he was pushing on an open door.

The monastics also had economic advantages that we probably wouldn’t. With institutions otherwise being weak, the monasteries were able to act as proto-capitalistic enterprises. If we are trying to make our own refuges, a key questions is what’s our economic advantage? Long-term, it might be more stable families and communities, but that doesn’t provide much immediate pull. Any thinking about new social arrangements needs to be directed to advantages that partly offset the increased costs. Spitballing, here’s a few possibilities:

- better mentorship and apprenticeship opportunities for the young?

- Tax advantages in having community services provided by the community instead of being purchased?

- Instant gentrification: a mass of decent people who have some kind of mutual commitment moving into an area at once could instantly change the character of the neighborhood and increase property values?

- Divorce-proofing and judgment-proofing and fine-proofing: it doesn’t sound very desirable morally, but I suppose certain communal arrangements could make assets and benefits relatively immune to divorce and legal judgments and fines?

- Decent schools and safe neighborhoods could function as non-monetary compensation and even be monetizable in some ways (e.g., run a daycare or a private school or even a charter school, something that attracts outsiders)

Final thought: the monastic model may work better in areas where Christianity is still socially dominant and where social capital is lower. Africa, perhaps Latin America, parts of Polynesia. Potentially even Eastern Europe and Russia, which are depopulating. There are big downsides to moving to these places, and its not just having less money. But the upsides increase when you have a group of people going with you. Call this variant of the Benedict Option the Pilgrim Option or the Volga German or Mennonite Option. Jewish immigration in Europe often took the same form. Historically, it worked best where the destination country had some kind of official welcome and protected status for the immigrants. Long-term, this option risks becoming a persecuted ethnic minority.

Exile:

Simple. Pick up your bags and leave. Is Canada more welcoming to the Christian life? Utah? Texas? Australia? Chile? Kenya? Jordan? Israel? Pick up and leave. It works best with some advance planning, a local network to smooth the transition, and a network of local network to spread the word about what countries and states are most hospitable. You can’t rely on the dominant media to tell you everything you want to know. It is especially attractive for the young. This is also a good option to put into action right away in emergencies if you’ve done a little advance work with passports, perhaps even dual citizenship, language acquisition, if you have a little bug-out money, and if your career is translatable. Right now, the need to leave quickly looks like a Black Swan, but its more thinkable then it used to be. Encouraging your children to have passports and to consider jobs that aren’t specific to one sovereignty (i.e., not law or government jobs) may be a plus.

Dhimmi Option

Dhimmitude is more like our situation then monasticism. We’re faced with a dominant belief system that doesn’t like us, that sees us as a threat ideologically, that wants to converts us and our children, that is or will be willing to impose cultural and legal and financial restrictions, but that probably isn’t going to shove us to the wall except in sporadic outbreaks. Our equivalent of the Mohammedan jizya may be thinks like stripping religious schools of accreditation, funding, and partnerships; de facto barring convinced Christians to certain professions, positions, or high-status jobs; protecting certain kinds of discrimination against Christians; or stripping churches and charitable donations to churches of their tax exempt status.

In most of the Middle East and North Africa, dhimmitude meant a gradual decline of Christianity. Nothing dramatic, mostly, especially in the middle stages. Death by ice, not fire. Coptic Christians went from something close to 100% of the population to something like 10% of the population. Christianity dominated in North Africa, but has been effectively at 0% there for centuries. In Lebanon and some other areas, on the other hand, Christians survived. What made the difference? More research needed. One important factor appears to have been birth rates, though. The declines seem to have been hardest where the successful people who were the most likely to remain convinced Christians had fewer children. How do we keep a strong commitment to children and family? Areas where Christian elites were more tightly integrated with common Christians also seem to have done better. What options are workable for upper middle class, urban, blue-collar, and rural Christians alike?

The Dhimmitude option is the default option. If we do nothing, this is what will happen. Under those circumstances, how do we adapt emotionally and spiritually to being low-status and despised? How do we keep our children strong in the faith? How do we handle poverty? On that front, something to recall is that the relative poverty in the First World actually isn’t that bad if you live around decent people. It’s not the deprivation, it’s the dysfunction. If you took a bunch of upper middle class people and made them live in a trailer park on $20,000/year, the trailer park would probably be a pretty nice place to live. It would be clean, safe, and orderly. There would be flower beds. A van would probably be set up to make library runs once or twice a day. Ditto runs to the grocery store and other necessities. There might be amateur theatricals. Gardens. Neighbors bringing the one family’s big screen outside so everyone could watch a movie. It’s largely a question of adapting expectations. Another expectation that may have to go is the expectation of not living with extended family, or of not sharing a home with another nuclear family. Remember, from a crudely practical perspective, the Tao offers a bunch of techniques for people to cooperate and get along. Christianity in particular is rich with these possibilities. So if we are willing and able to share homes temporarily or permanently and accept other kinds of living arrangements that are closer then the autonomists can tolerate, we have a defense in depth that they won’t have anticipated.

Mozarabic option

In Cordoba under the Caliphs, the Mozarabic Christians were not officially persecuted, much. But they were dhimmis. Some professions were barred them. They were taxed. They were only allowed a limited number of churches, with some restrictions on expanding or even repairing the ones they had. They weren’t allowed to preach, for the most part. Educated Mozarabs learned Arabic, not Latin. They tended to emphasize those aspects of Christian belief and practice that were the least offensive to the ruling Muslims (sound familiar?). In the 9th century, the martyrs of Cordoba gave the faith a fresh impetus. They would go into public places or before the Caliph and revile Mohammed, or proclaim that Christ was begotten and God. Then they’d be martyred. They were controversial even then, because they were provoking their own martyrdom. There are potential modern parallels. When is prudence and keeping your head down actually harmful, and when is it wise?

Can the Mozarabic Option work without a Reconquista, which we don’t have?

Ghetto Option

The Jews have a long and varied history of thriving as a despised minority. For Taoists, this history bears a lot more study. A few very preliminary points is that they looked out for each other in a form of basic social welfare, that they were willing to shed members who didn’t fit in, and that they were able to specialize in low-status professions such as money-lending that gave them a niche. What are low-status or despised economic niches that Christians could fill? Childcare, manual labor, oil and gas, logging, security, tax collection? The problem is that doing despised work makes you even more despised. It’s a vicious cycle. But no one option can be ideal. We are talking about a choice of evils here.

Deseret option

Breaking up the US into multiple Republics would probably be a boon for religious liberty. Heck for liberty and diversity generally. But it’s not a realistic option.

Meta-church option

There is little historical precedent for different denominations and even faiths forming institutional ties while maintaining their religious distinctiveness and exclusive truth and salvation claims. It needs to happen anyway. We can’t make it while on our own. These institutional ties don’t need to be strong. Even something like websites where professionals could do business with each other, or various religious schools banding together to form their own accreditation agency, would matter. If each variety of Taoist is thrown back on their own resources, we are probably doomed.

Amish Option

Dreher rules out going Amish, i.e., drastically withdrawing from the world. So does most everybody else. But do we dislike drastic withdrawal because it’s not a good plan or because the world is too much with us? By objective measures, the Amish are wildly successful. The Hasidim are probably a successful model of drastic withdrawal. Are there others? What forms can drastic withdrawal take? Is drastic withdrawal compatible with missionary work? Deseret probably qualifies as a successful form of drastic withdrawal that was compatible with missionary work, though conditions have changed.

Speculation: the key technique here seems to be a form of psychological engineering. The Amish are not, in fact, completely withdrawn from mainstream society. G. from this website has an Old Order Amish family that he is close to because their children were both in the cancer ward in the hospital for the same months. But the Amish act differently enough that psychologically they aren’t part of the society any more, so its safe to let them do their own thing. Muslims seem to benefit from the same psychological exception. Muslim traditionalism doesn’t bother the left because Muslims are exotics. What practices or customs are available to Taoists that would allow mainstream society to treat us as oddballs, instead of as threats?

Millet Option

The Ottoman millets, if they were a variant on dhimmitude, were a variant that seems to have been pretty favorable to Christians. I don’t know enough to comment, but what little I know suggests that this isn’t a very applicable model. Comment is welcome.

Hasidic Option

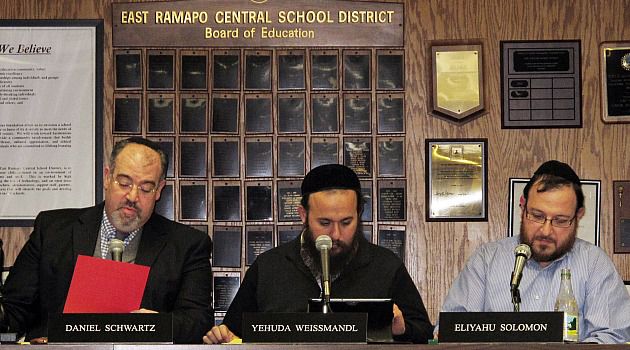

You’ve probably read how Hasidim in New York were able to protect their interests by bloc voting, The Mormons in Nauvoo did something similar. (In the Mormon case, it backfired pretty badly.)

Christian voters haven’t made much difference and won’t make much difference, as long as we continue to vote as we have done before. That doesn’t mean that all voting is useless. A bloc that focuses on a narrower slate of issues could still get its way. What are the minimum political issues that Benedict Option bloc voters should insist on? Here are a few suggestions:

- Religious liberty, natch;

- Parental rights;

- Security from violence or confiscation;

- Disestablishing education, credentials, licensure, and other gatekeeping mechanisms;

- Homeschooling; vouchers;

- Child tax credits;

- Zoning laws and other legal impediments to intentional communities;

- Privacy law tweaks that make it harder to expose people like Eich;

- Workplace protection rules.

I don’t think these are all a good idea. I also suspect that most religious voters would hesitate to give up issues like abortion that don’t affect the Benedict Option. But for a Benedict Option to work, religious voters would have to be willing to give up culture war material and focus on retrenchment. (Perhaps not abortion specifically, since at least some pro-life tweaks are fairly popular).

OK, over to you. Your observations and suggestions?

Continue reading at the original source →