The Know

The existence of the Book of Mormon has motivated Latter-day Saints since the days of Joseph Smith to find evidence that corroborates the book’s historical claims. Joseph Smith, on a few occasions, offered speculative arguments for the book’s authenticity by drawing from what was known in his day about ancient American antiquities.1 Beginning in the Prophet’s lifetime, the unfortunate creation and circulation of unproven artifacts, modern forgeries, and other hoaxes began. Some have connected a few of these forgeries to the Book of Mormon or Latter-day Saint history specifically, while other falsified artifacts have been associated with the Book of Mormon indirectly.

The Kinderhook Plates

In May 1843, Joseph Smith was presented with six small, bell-shaped brass plates with engravings on them. The plates had allegedly been excavated in the town of Kinderhook, Illinois and were brought to the Prophet with hopes that he could translate the engravings. Apostle Parley P. Pratt believed the plates contained “the genealogy of one of the ancient Jaredites back to Ham the son of Noah.”2 A non-Mormon visitor to Nauvoo reported a rumor in the city that “the figures or writing on [the plates] was similar to that in which the Book of Mormon was written,” and that “by the help of revelation [Joseph Smith] would be able to translate them. So, a sequel to that holy book may soon be expected.”3

Joseph Smith did offer some preliminary observations about what he thought the plates might contain, but no translation was ever produced.4 For many years Latter-day Saints thought the plates were authentic,5 even though one of the men involved in their “discovery” admitted they were fraudulent.6 Many years later, scientific study would demonstrate that the plates were in fact modern forgeries. This has been the position of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints ever since.7

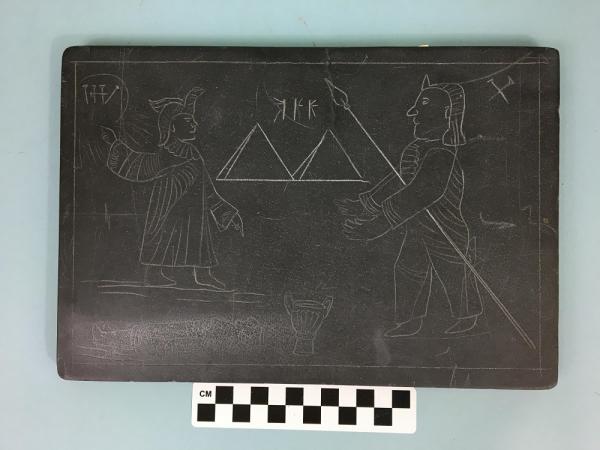

The Michigan Relics

Another set of forgeries connected with Latter-day Saint history are the so-called “Michigan Relics.” Beginning in 1890, “hundreds of objects . . . were made to appear as the remains of a lost civilization. The artifacts were produced, buried, ‘discovered,’ and marketed by James O. Scotford and Daniel E. Soper. For three decades these artifacts were secretly planted in earthen mounds, publicly removed, and lauded as wonderful discoveries.”8 Many of these artifacts included clear depictions of biblical events such as the Creation, the Flood, Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac, and the life of Christ. “Because the Michigan Relics allegedly evidence a Near Eastern presence in ancient America, they have drawn interest from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as well as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.”9

Elder James E. Talmage became interested in the artifacts at one point and was tasked by the First Presidency to investigate their authenticity. Talmage himself saw the clear importance these artifacts would hold for the Book of Mormon if they were genuine, but was careful not to accept them at face value and continued his investigation. Ultimately, as with most professionals at the time, Talmage concluded “after considerable scientific experiment and some detective work” that the artifacts were fraudulent.10 This conclusion continues to be the consensus among scholars from both inside and outside the Church.11

The Newark Holy Stones

The artifacts known today as the Newark Holy Stones were allegedly discovered in 1860 by a man named David Wyrick at a site near Newark, Ohio. The artifacts consist of: (1) the Keystone, or a stone with Hebrew inscriptions on its four sides, (2) the Decalogue Stone, which includes a supposed image of Moses and Hebrew text of the Ten Commandments running along its sides, nested in a sandstone box, and (3) a stone bowl.12

Almost immediately after their “discovery” the artifacts were met with skepticism.13 Errors in the Hebrew text was one of the major red flags raised by experts who examined the stones.14 Despite continued attempts to authenticate the artifacts,15 skepticism has persisted among mainstream archaeologists down to the present.16

The Los Lunas Decalogue Stone

Located near Los Lunas, New Mexico sits a large flat stone covered with “an abbreviated version of the Ten Commandments in a variant ancient Semitic alphabet.”17 Called the Los Lunas Decalogue Stone or Commandment Rock, the first recorded encounter with the stone was in 1933 by the archaeologist Frank Hibben,18 although a “plausible” but unconfirmed sighting of the stone may have occurred in the 1870s.19

The debate surrounding the stone is whether the Semitic inscription upon it is authentically ancient. While the inscription “is carved in an ancient form of Hebrew . . . the identification of the carver remains a mystery.”20 The archaeologist and linguist Cyrus Gordon accepted the authenticity of the inscription and argued that it was “Old Phoenician/Hebrew” and perhaps functioned as a sort of mezuzah, or an ornamental case inscribed with passages from the Torah and used by Jews to mark entrances of homes and synagogues.21

This theory, however, has not gained widespread acceptance. Most scholars, including Latter-day Saint scholars, regard the inscription as fraudulent.22 As with the Newark Holy Stones, problems with the language and preservation of the inscription have been raised.23 Skeptics also point out the lack of clear archaeological attestation of a Hebrew culture in the surrounding area.24 Curiously, some have even suggested—without any concrete evidence—that the inscription was fabricated by Latter-day Saints living in the area!25

The Bat Creek Stone

Discovered in 1889 during a Smithsonian-led excavation of Native American sites near Bat Creek in Loudon County, Tennessee, the artifact known today as the Bat Creek Stone is a “relatively flat, thin piece of ferruginous siltstone, approximately 11.4 cm long and 5.1 cm wide.”26 On the stone is an inscription of about eight characters written horizontally across the surface. In the publication of his field notes, the director of the excavation, Cyrus Thomas, declared the inscription on the stone to be “beyond question letters of the [modern] Cherokee alphabet.”27

Excitement over the stone increased when Cyrus Gordon published arguments that the inscription on the stone was ancient Hebrew and read “for Judea” or “for the Judeans.”28 According to Gordon, the inscription lends credibility to the idea that ancient Jews successfully migrated to the New World.29

In recent years, the authenticity of the inscription has come under critical scrutiny. John Emmert, Thomas’ assistant who was the one to actually excavate the mound where the stone was discovered, has been charged with forging of the characters on the stone by using available nineteenth century sources.30 Gordon’s contention that the characters are authentic ancient Hebrew has likewise been challenged.31 While some have continued to defend the authenticity of the inscription,32 the Smithsonian itself now regards it as fraudulent.33

The Why

The motives behind why people might forge artifacts vary. In the case of the Kinderhook Plates, the forgers wanted to embarrass Joseph Smith by tricking him into translating bogus plates. In the case of the Michigan Relics, financial reward appears to have been the motive behind their fabrication. In other instances, the motives might range from gaining notoriety and fame to proving a pet theory or religious or political worldview.34

Whatever the case may be, frauds, hoaxes, and dubious artifacts should be rejected by Book of Mormon students and defenders. It does the Book of Mormon no favors to use fraudulent or questionable evidence on its behalf, and can very easily backfire by creating deeper mistrust and suspicion on the part of those who may have sincere doubts or questions about the book’s authenticity.35 The overly zealous use of fraudulent evidence in defending the Book of Mormon is likewise deplorable because it cheapens and delegitimizes the excellent real scholarship which has been produced on the book.36

At a devotional for the Church Educational System’s religious educators, Elder M. Russell Ballard offered “a word of caution not to pass along faith-promoting or unsubstantiated rumors or outdated understandings and explanations of our doctrine and practices from the past.” He further urged to “consult the works of recognized, thoughtful, and faithful LDS scholars to ensure you do not teach things that are untrue, out of date, or odd and quirky.”37

This is wise counsel, which every Latter-day Saint should heed when being presented with questionable or unprovenanced artifacts, especially so when such artifacts seem “too good to be true” or when they are presented by individuals who have ideological or financial motives.

The Prophet Joseph Smith declared that the Latter-day Saints “believe in being honest” (Article of Faith 13). Knowingly using frauds and hoaxes as evidence for the Book of Mormon is not only poor scholarship but is, ultimately, dishonest. This is different from scholars debating the significance or meaning of real artifacts and historical sources. Academic disagreement over disputed issues of history and archaeology is commonplace, and part of the process of scholarship.

Latter-day Saints should naturally be a part of the scholarly conversation surrounding the historicity of the Book of Mormon. They should emphatically not, however, accept or promote the use of frauds, forgeries, or dubious artifacts, even if such items seem to support the Book of Mormon’s claims.

Further Reading

Mark Alan Wright, “Joseph Smith and Native American Artifacts,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 119–40.

Mark Ashurst-McGee, “Mormonism’s Encounter with the Michigan Relics,” BYU Studies 40, no. 3 (2001): 174–209.

Hugh Nibley, “Zeal Without Knowledge,” in Approaching Zion, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 9 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1989), 63–84.

- 1. See Mark Alan Wright, “Joseph Smith and Native American Artifacts,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2015), 119–140.

- 2. Brian M. Hauglid, “‘Come & Help Build the Temple & City’: Parley P. and Orson Pratt’s May 1843 Letter to John Van Cott,” Mormon Historical Studies 12, no. 7 (Spring 2011): 155.

- 3. Charlotte Haven, “A Girl’s Letters from Nauvoo,” Overland Monthly 16, no. 96, December 1890, 630; letter written May 2, 1843.

- 4. For a summary of the event and the historical sources, see Book of Mormon Central, “What Do the Kinderhook Plates Reveal About Joseph Smith’s Gift of Translation?” KnoWhy 454 (July 31, 2018).

- 5. See for instance B. H. Roberts, New Witnesses for God, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret News, 1909), 3:58–64.

- 6. Wilbur Fugate to James T. Cobb, June 30, 1879, in Wilhelm Wyl (Wymetal), Mormon Portraits (Salt Lake City, UT, 1888), 207–208.

- 7. Stanley B. Kimball, “Kinderhook Plates Brought to Joseph Smith Appear to Be a Nineteenth Century Hoax,” Ensign, August 1981, online at lds.org.

- 8. Mark Ashurst-McGee, “Mormonism’s Encounter with the Michigan Relics,” BYU Studies 40, no. 3 (2001): 175.

- 9. Ashurst-McGee, “Mormonism’s Encounter with the Michigan Relics,” 175.

- 10. Ashurst-McGee, “Mormonism’s Encounter with the Michigan Relics,” 182–191, quote at 190.

- 11. Richard B. Stamps, “Tools Leave Marks: Material Analysis of the Scotford-Soper-Savage Michigan Relics,” BYU Studies 40, no. 3 (2001): 211–238; Kenneth Feder, Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology, 8th ed. (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2014), 170–171.

- 12. An overview and history of the artifacts can be found in Robert W. Alrutz, “The Newark Holy Stones: The History of An Archaeological Tragedy,” Journal of the Scientific Laboratories of Denison University 57 (1980): 1–57.

- 13. Alrutz, “The Newark Holy Stones,” 14–17, 39–47.

- 14. See the authorities cited in Bradley T. Lepper, “Newark’s ‘Holy Stones’: the Resurrection of a Controversy,” in Newark “Holy Stones”: Context for Controversy, Public Symposium, Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum, Coshocton, Ohio, Saturday, November 6, 1999, ed. Patti Malenke (Coshocton, OH: Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum, 1999), 16.

- 15. J. Huston McCulloch, “An Annotated Transcription of the Ohio Decalogue Stone,” The Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers 21 (1992): 56–71; David Allen Deal, “The Ohio Decalog [sic]: A Case of Fraudulent Archaeology,” Ancient American 2, no. 11 (May/June 1996): 10–19.

- 16. Stephen Williams, Fantastic Archaeology: The Wild Side of North American Prehistory (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991), 167–176; Bradley T. Lepper, “The Newark ‘Holy Stones’: The Social Context of an Enduring Scientific Forgery,” online; Bradley T. Lepper et al, “Civilization Lost and Found: Fabricating History,” Skeptical Inquirer, November/December 2011, 50–52.

- 17. William R. McGlone et al., Ancient American Inscriptions: Plow Marks or History? (Sutton, MA: Early Sites Research Society, 1993), 18.

- 18. James D. Tabor, “An Ancient Hebrew Inscription in New Mexico: Fact or Fraud?” United Israel Bulletin 59 (Summer 1997): 1–3, online.

- 19. McGlone et al., Ancient American Inscriptions, 18.

- 20. Ferenc M. Szasz, “Pre-Columbian Contacts in the American Southwest: Theories and Evidence,” New Mexico Humanities Review 5, no. 1 (1982): 53.

- 21. Cyrus Gordon, “Diffusion of Near East Culture in Antiquity and in Byzantine Times,” Orient 30–31 (1995): 69–70.

- 22. Welby W. Ricks, “A Purported Phoenician Inscription in New Mexico,” in Papers of the Fifteenth Annual Symposium on the Archaeology of the Scriptures, ed. Ross T. Christensen (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1964), 94–100; Hugh Nibley, The Prophetic Book of Mormon, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 8 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1989), 63.

- 23. Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews, “The Los Lunas Inscription,” online; Feder, Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries, 139–140.

- 24. Kenneth L. Feder, Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum (Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2010), 161–162; Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries, 139.

- 25. H. W. Stowell, “Mystery Inscriptions,” New Mexico Magazine, August 1961, 27; David Allen Deal, Discovery of Ancient America (Irvine, CA: Kherem La Yah Press, 1984), 3; Szasz, “Pre-Columbian Contacts in the American Southwest,” 53; Fitzpatrick-Matthews, “The Los Lunas Inscription.”

- 26. Robert C. Mainfort, Jr. and Mary L. Kwas, “The Bat Creek Stone: Judeans in Tennessee?” Tennessee Anthropologist 16 (Spring 1991): 3.

- 27. Cyrus H. Thomas, “Bat Creek Mounds,” in Twelfth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1890–91, ed. J. W. Powell (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894), 393.

- 28. Cyrus Gordon, “The Bat Creek Inscription,” in Book of the Descendants of Doctor Benjamin Lee and Dorothy Gordon (Ventor, NJ: Ventor Publishers, 1972), 5–18; “New Directions in the Study of Ancient Middle Eastern Cultures,” Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Cultural Center in Japan 5 (1991): 62–63; “A Hebrew Inscription Authenticated,” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, 27 March 1990, ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 67–80.

- 29. See further Barbara Ford, “Semites First in America?” Biblical Archaeologist 41, no. 3 (September 1978): 43–53; J. Huston McCulloch, “Did Judeans Escape to Tennessee?” Biblical Archaeology Review, July/August 1993, 47–53.

- 30. Mainfort and Kwas, “The Bat Creek Stone: Judeans in Tennessee?” 1–19; “The Bat Creek Fraud: A Final Statement,” Tennessee Anthropologist 18 (Fall 1993): 87–93; “The Bat Creek Stone Revisited: A Fraud Exposed,” American Antiquity 64 (Oct. 2004): 761–769.

- 31. P. Kyle McCarter, Jr., “Let’s be Serious About the Bat Creek Stone,” Biblical Archaeology Review 19, July/August 1993, 54–55, 82–83.

- 32. J. Huston McCulloch, “The Bat Creek Stone Revisited: A Reply to Mainfort and Kwas in American Antiquity,” online.

- 33. E-mail dated Feb. 7, 2014 from Jake Homiak, Director, Anthropology Collections & Archives Program, Smithsonian Museum Support Center, Suitland MD, to Barbara Duncan, Education Director, Museum of the Cherokee Indian, Cherokee NC, cited in “Bat Creek inscription,” online.

- 34. The latter seems to be the motive behind the forging of the Newark Holy Stones. See Lepper, “Newark’s ‘Holy Stones’,” 14–15.

- 35. A point raised and illustrated with a tragic real-world example in J. Michael Hunter, “The Kinderhook Plates, the Tucson Artifacts, and Mormon Archaeological Zeal,” Journal of Mormon History 31, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 65–70.

- 36. Hunter, “The Kinderhook Plates, the Tucson Artifacts, and Mormon Archaeological Zeal,” 63–65.

- 37. M. Russell Ballard, “By Study and By Faith,” Ensign, December 2016, 27.

Continue reading at the original source →