The Know

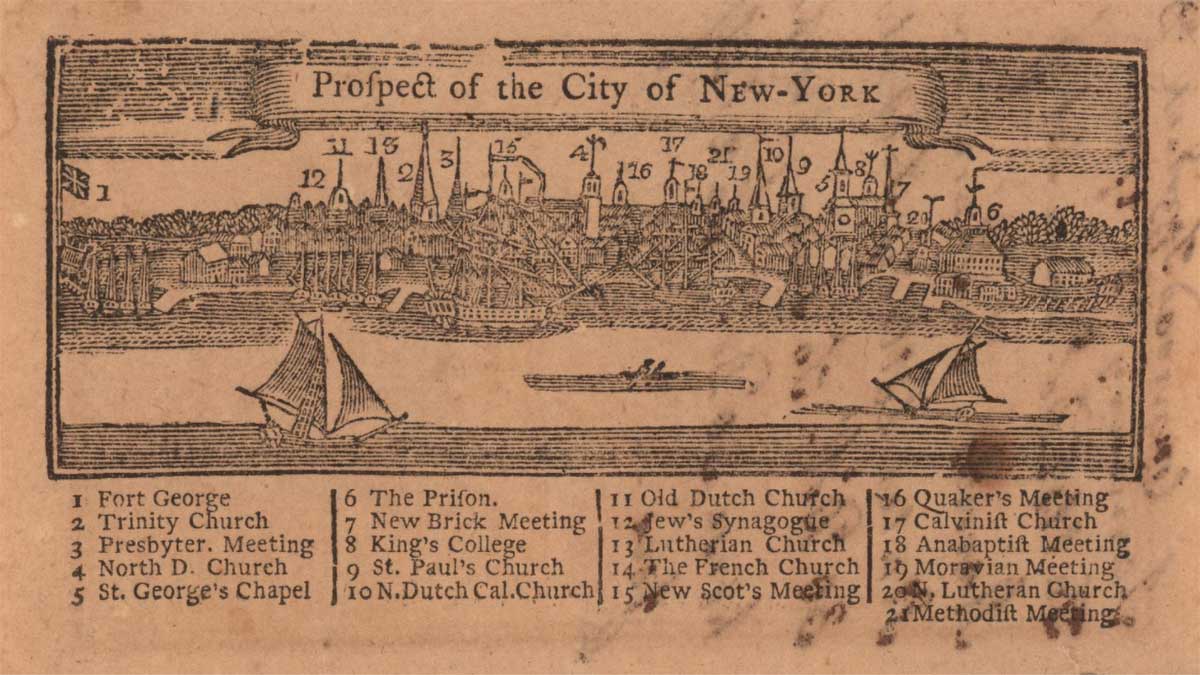

For a young Joseph Smith living on the frontier of western New York in the early 1800s, amidst a cacophony of religious fervor from various denominations established in the vicinity, the burning question of the day was, which church should he join? Which one was right? (Joseph Smith—History 1:10). For many young Americans today—who take for granted a strong and longstanding tradition of religious liberty and the veritable religious marketplace it provides—Joseph’s question is beginning to sound quaint and old fashioned.

In 1820, however, it was a heady and cutting-edge question for the rising generation of the still young American Republic. Never before in history had joining a church of one’s own choosing been such a ready and accessible option. Historical commentary on Joseph Smith’s First Vision and earliest religious inclinations has generally focused on the immediate moment and context—the “burned over district” of upstate New York during the Second Great Awakening—of Joseph’s question.1 Fully understanding and appreciating why there were so many different churches to choose from and how Joseph responded to his circumstances, however, requires looking more fundamentally at the development of religious freedom in the American colonies and Joseph Smith’s family heritage of religious independence.

Beginning in the 1620s, the Puritan Pilgrims came to North America looking for a religious refuge. They believed the Church of England was in error, and wanted a chance to build a society based on biblical laws and principles.2 In doing so, however, they (like their persecutors in England) “subscribed to the view … that civil authorities must assist the church in maintaining religious uniformity.” Thus, as James H. Hutson, Director of the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, has explained, “The Puritans had no quarrel with the English government’s policy, under which they suffered, of imposing on the realm one true religion; they disagreed only over what one religion was true.”3

It was Roger Williams, a Puritan dissenter driven out of Massachusetts, who first established Rhode Island as a refuge “where government would not interfere with religious beliefs and practices.”4 In the 1680s, William Penn, a Quaker, similarly wrote “religious freedom into the law of the land” when establishing Pennsylvania.5 Eventually, as more and more people poured into the British colonies in the New World, many colonies still sponsored specific churches, but they also allowed for increased toleration of persons with differing religious views.

After the Revolutionary War, religious freedom was enshrined into the law of the newly established republic through the Bill of Rights in 1791, which forbade the federal government through Congress from making any “law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This did not immediately remove the state and federal governments completely from involvement in religious matters, however. The law was still developing as the new nation and the various states were still trying to figure out church-state relations. Many still felt that only a deeply religious society could function and flourish, and so it was widely believed that government had a responsibility to act as a “nursing father” to the church.6 The federal government could support religion in various ways, including through financial means, as long it did not exclusively favor one sect above all others.

Furthermore, the Bill of Rights only limited the powers of the federal government. At the state and local level, specific churches were sometimes directly sponsored and financially supported through taxes. These legal developments had a direct impact on the worship and practices of Joseph Smith’s family and progenitors.7

For example, in 1813 Joseph’s uncle, Jesse Smith, was living in Turnbridge, Vermont, where the local church had recently hired a Congregationalist minister with whom Jesse had serious disagreements. Vermont law not only allowed the local populace to appoint its own ministers, but it also allowed towns to levy a tax by majority vote in order to support local ministers. Failure to pay this tax could result in foreclosure on one’s property to help pay a minister’s delinquent salary.8

In keeping with some measure of religious freedom, however, the Vermont law made exceptions available to those who were of a different religious persuasion than that supported by the majority vote. To be exempted from the tax, a person had “to enter his dissent, in writing, on the records of the town or parish.”9 Consistent with this law, Jesse Smith formally drafted a certificate of dissent, entering his “protest” against the Church’s choice of minister and articulating the theological convictions behind his decision to withdraw.10

In 1813, right as Jesse was in the process of protesting the new minister, young Joseph Smith traveled with him to Salem, Massachusetts. Joseph was recovering from his painful leg operation, and it was believed that the sea air would be therapeutic. John W. Welch noted, “Although no evidence exists of what these two traveling companions talked about … it is not hard to imagine that topics of religion often came up.”

Their conversations could well have turned to the subjects that Jesse felt so strongly about at this very time and which he expressed so clearly in his 1814 protest. One can well imagine the impact Jesse’s bold action might have had on the young Joseph’s views of many matters concerning religious freedom and doctrinal necessity.11

The Why

By 1820, religious freedom had been spreading and developing in America for nearly two hundred years. These centuries worth of developments increasingly allowed people to follow their own religious conscience, as Joseph’s uncle Jesse had. With no governmental restrictions on religious liberty, new churches and denominations sprang up at an unprecedented rate, making it easier than ever to find and join a church. It also had opened up a new frontier of religious development. Churches competed with each other for popular and financial support. Ministers debated points of doctrine based on tradition, logic, and interpretation; and the various denominations adopted or subscribed to particular creeds, which often drew religious battle lines more than they offered expressions of faith.12

While this is exactly what led Joseph to confusion and bewilderment, it is also what provided him the freedom to ponder and consider—without fear of legal repercussion—“Who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?” (Joseph Smith—History 1:10). Not only was he free to ask these questions, but he was free to seek answers and to follow those answers wherever they led him.

These legally granted religious freedoms made the Restoration possible. It is also what made it possible for many others to listen to and hear the message of the Restoration, and follow their own conscience and spiritual promptings to join the restored Church of Jesus Christ.

Further Reading

John W. Welch, “The Smiths and Religious Freedom: Jesse Smith’s 1814 Church Tax Protest,” in Sustaining the Law: Joseph Smith’s Legal Encounters, ed. Gordon A. Madsen, Jeffrey N. Walker, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2014), 39–50.

John W. Welch, “‘All Their Creeds Were an Abomination’: A Brief Look at Creeds as Part of the Apostasy,” in Prelude to the Restoration,” in Prelude to the Restoration: From Apostasy to the Restored Church (Salt Lake City and Provo: Deseret Book and the BYU Religious Studies Center, 2004), 228–249.

James H. Hutson, “‘Nursing Fathers’: The Model for Church-State Relations in America from James I to Jefferson,” in Lectures on Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2003), 7–23.

Richard Lloyd Anderson, Joseph Smith’s New England Heritage: Influence of Grandfathers Solomon Mack and Asael Smith, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Press, 2003).

- 1. See, for example, Milton V. Backman, Joseph Smith’s First Vision: Confirming Evidences and Contemporary Accounts, rev. and enlarged ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980).

- 2. On the influence of biblical law in America, see John W. Welch, “Biblical Law in America: Historical Perspective and Potentials for Reform,” in Lectures on Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2003), 49–66.

- 3. James H. Hutson, Religion and the Founding of the American Republic (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1998), 7.

- 4. Hutson, Religion and the Founding, 8. See also Jeffrey R. Holland, “Prophets, Seers, and Revelators,” General Conference, April 2004: “In the tumultuous years of the first settlements in this nation, Roger Williams, my volatile and determined 10th great-grandfather, fled—not entirely of his own volition—from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and settled in what is now the state of Rhode Island. He called his headquarters Providence, the very name itself revealing his lifelong quest for divine interventions and heavenly manifestations. But he never found what he felt was the true New Testament church of earlier times. Of this disappointed seeker the legendary Cotton Mather said, “Mr. Williams [finally] told [his followers] ‘that being himself misled, he had [misled them,’ and] he was now satisfied that there was none upon earth that could administer baptism [or any of the ordinances of the gospel], … [so] he advised them therefore to forego all … and wait for the coming of new apostles.” Roger Williams did not live to see those longed-for new Apostles raised up, but in a future time I hope to be able to tell him personally that his posterity did live to see such.”

- 5. Hutson, Religion and the Founding, 11.

- 6. See James H. Hutson, “‘Nursing Fathers’: The Model for Church-State Relations in America from James I to Jefferson,” in Lectures on Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2003), 7–23.

- 7. See Richard Lloyd Anderson, Joseph Smith’s New England Heritage: Influence of Grandfathers Solomon Mack and Asael Smith, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Press, 2003).

- 8. John W. Welch, “The Smiths and Religious Freedom: Jesse Smith’s 1814 Church Tax Protest,” in Sustaining the Law: Joseph Smith’s Legal Encounters, ed. Gordon A. Madsen, Jeffrey N. Walker, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2014), 41–42.

- 9. 1801 Vermont Laws, November 3, 1801, Section 3, Proviso 2, as cited in Welch, “Smiths and Religious Freedom,” 43.

- 10. See Jesse Smith’s full certificate of dissent in Welch, “Smiths and Religious Freedom,” 45–50.

- 11. Welch, “Smiths and Religious Freedom,” 44.

- 12. John W. Welch, “‘All Their Creeds Were an Abomination’: A Brief Look at Creeds as Part of the Apostasy,” in Prelude to the Restoration,” in Prelude to the Restoration: From Apostasy to the Restored Church (Salt Lake City and Provo: Deseret Book and the BYU Religious Studies Center, 2004), 228–249.

Continue reading at the original source →