Download Print-Friendly Version</a

Download Print-Friendly Version</a

Most people instinctively lean on one or two ways of handling conflict: a favorite approach and a fallback when the first doesn’t work. Yet there are five conflict management styles, and all five are necessary in fostering healthy relationships. The challenge is learning to use the right style at the right time. Which styles do you default to? And which should you start implementing?

This article is part of a series pairing short, humorous videos created by TheFamilyProclamation.Org with articles published by Public Square offering deeper explorations of the theory and doctrine of Peacemaking. Each installment pairs academic theory with Christian teachings for resolving everyday disagreements.

Today’s video shows examples of using all five conflict management styles when there are two people, but only one slice of pizza left.

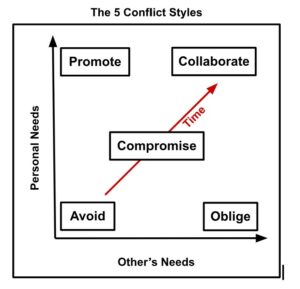

The five styles introduced here are based on the Thomas–Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument: Oblige, Promote, Collaborate, Compromise, and Avoid. It’s helpful to consider the five styles based on people’s needs: your needs and the needs of others. And, the amount of time and effort each style takes. The consequence of unmet needs either in oneself or others is the strong negative emotion of resentment. No one style is inherently right or wrong. The key lies in discerning which approach fits the situation.

Oblige

Obliging means yielding to another’s needs. When the issue matters more to them than to oneself, in conflict theory, it reflects a low concern for personal needs and a high concern for others’ needs. This style can de-escalate tensions, promote gratitude, and acknowledge the importance of another’s perspective. However, overuse may neglect essential personal needs.

A scriptural example comes from Abraham and Lot in Genesis 13. When their herdsmen quarreled over land, Abraham obliged: “Let there be no strife, I pray thee, between me and thee … for we be brethren … If thou wilt take the left hand, then I will go to the right; or if thou depart to the right hand, then I will go to the left.” Lot chose the fertile Jordan Valley, while Abraham accepted the less desirable land. Abraham’s willingness to accommodate preserved peace between their households.

In the 1840s, a devastating blight destroyed Ireland’s potato crops, leading to mass starvation and disease. The U.S. government took direct action. President James K. Polk ordered the naval vessel USS Jamestown to be filled with provisions and sent to Ireland in 1847. This was followed by widespread public fundraising and additional aid from the government. The U.S. decision was driven by empathy for the suffering Irish population, many of whom had emigrated to America. The action was taken with no expectation of political or financial compensation. While it did strengthen the relationship, the United States’ response to the Irish Potato Famine was an obliging act motivated by a sense of goodwill and compassion.

Pros: Defuses tension quickly; communicates care for the other’s perspective; allows movement forward when personal cost is minor.

Cons: Can create resentment if personal needs are repeatedly ignored; risks imbalance in relationships; may enable others’ selfishness.

Iconic statement: “This matters more to you than to me—take it.”

Promote

Promoting involves asserting one’s own needs. When the issue is of high importance personally but less critical for others, in conflict theory, this reflects a high concern for personal self-needs and a lower concern for others’. Used wisely, it preserves integrity, sets boundaries, respect, and prevents neglect of essential personal responsibilities.

Scripture records Esther as a profound example. When the Jews of Persia faced extermination, Esther risked her life by approaching King Ahasuerus unbidden. “If I perish, I perish” (Esther 4:16). Her boldness in promoting her people’s survival turned the tide of history.

In modern history, Susan B. Anthony exemplified this style through tireless advocacy for women’s suffrage. Willing to endure arrest and ridicule, she insisted, “Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.” By promoting her cause with unrelenting persistence, she advanced the rights of countless women.

Pros: Safeguards essential personal needs; establishes clear boundaries; brings neglected issues to light.

Cons: Can appear and even become domineering; risks escalating conflict; may undermine relationships if used unnecessarily.

Iconic statement: “This matters deeply to me—I must stand for it.”

Collaborating

Collaborating seeks solutions that fully meet the needs of all parties. In theory, it reflects a high concern for both self and others. It is the most time-intensive and demanding style, but also the one most likely to generate durable, creative, and mutually satisfying resolutions.

A scriptural example appears in the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15), where early Christians debated whether Gentile converts must keep the law of Moses. Through deliberation and testimony, leaders forged a collaborative solution: Gentiles would not be required to keep the full law but were asked to respect certain practices for the sake of unity. This preserved inclusion without dissolving moral standards.

In history, Nelson Mandela exemplified collaboration during South Africa’s transition away from apartheid. Instead of seeking revenge, his inclusive multiracial leadership in the African National Congress, personal mentorship of Springbok rugby captain Francois Pienaar, and his willingness to work with political rivals Mandela established a democratic framework, preventing civil war and opening a path toward reconciliation.

Pros: Builds trust; generates creative solutions; addresses the deepest needs of all parties.

Cons: Requires significant time and energy; can stall if parties are unwilling; may be impractical in urgent conflicts.

Iconic statement: “Let’s stay at the table until we find a solution that works for all of us.”

Compromising

Compromising involves each party yielding part of their needs to reach a middle ground. In theory, it balances moderate concern for self and others. It does not produce perfect satisfaction but provides workable solutions when time is short or stakes are moderate.

A scriptural example appears in the division of land among Israel’s tribes. The tribe of Reuben and Gad requested land east of the Jordan, which initially angered Moses. A compromise was reached: they could settle eastward provided their soldiers helped the other tribes secure their inheritance west of the Jordan (Numbers 32).

In history, the Missouri Compromise of 1820 illustrates this principle. Balancing free and slave states preserved the fragile union for a time, though deeper moral questions remained unresolved.

Pros: Creates quick, workable solutions; is often perceived as “fair”; avoids stalemates; spreads sacrifice across parties.

Cons: Often leaves no one fully satisfied; can defer deeper issues; risks fostering half-measures instead of real resolution.

Iconic statement: “I’ll give some, you give some, and we’ll both move forward.”

Avoiding

Avoiding means stepping away from conflict altogether, either by deferring, delaying, or disengaging. In theory, it reflects low concern for the needs of both self and others in the conflict. Avoidance may preserve peace when the issue is trivial, the relationship is distant or unimportant, or when emotions are too high for productive discussion. But, avoidance risks creating resentment if used habitually in close or necessary relationships.

Scripture shows Jesus withdrawing after intense disputes with religious leaders: “And Jesus went about Galilee: for he would not walk in Jewry, because the Jews sought to kill him” (John 7:1). His withdrawal shows discernment for choosing the right moment to disengage. But on another occasion, when confronted by opponents trying to trap him with a question about paying taxes to Caesar, Jesus asked to see a coin and noted that it bore Caesar’s image. He then responded, “Render therefore unto Caesar the things which be Caesar’s, and unto God the things which be God’s.” Though He engaged with those promoting a conflict, this encounter is still an example of conflict avoidance because Jesus shifted the conversation to a moral lesson rather than engaging in the political debate his opponents intended.

As president, George Washington witnessed the growing animosity between factions, which he feared would destroy the republic from within. Instead of staying in office to fight the factions, Washington retired, setting a critical precedent for a peaceful transfer of power. By doing so, he removed his unifying but also polarizing presence, forcing the political system to mature on its own. His farewell address served as a final, non-partisan warning. George Washington’s retirement is an example of avoidance, as he intentionally disengaged from political power to prevent the young nation from being torn apart by deepening partisan conflict. By contrast, Mahatma Gandhi continually engaged in politics utilizing strategic avoidance through nonviolent resistance. By refusing to meet violence with violence, he avoided direct clashes while still advancing his cause, exhausting the will of his opponents without reciprocating hostility.

Pros: Allows time for cooling off; prevents escalation over trivial matters; creates space for reflection.

Cons: Can leave problems unresolved; risks long-term resentment; may erode trust if avoidance becomes habitual.

Iconic statement: “This conflict doesn’t need to be fought right now.”

“O Be Wise”

We may be particularly gifted or prone to using one or two of the styles, but no single style is sufficient for every situation. Scripture and history affirm that wisdom lies not in clinging to one or two styles but in discerning which approach serves the moment best. Some say knowledge comes from facts, but wisdom comes from experience. Learn from the experience of others and, in counsel with God, discern which style to resolve every conflict in life. Conflict is inevitable, but considering the full range of conflict styles transforms disagreements into robust opportunities for growth, justice, and deeper connection: don’t just default to one or two styles. So even though we may be “as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves” (Matthew 10).

The post Why Winning Doesn’t Make You Right: Five Conflict Styles appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →