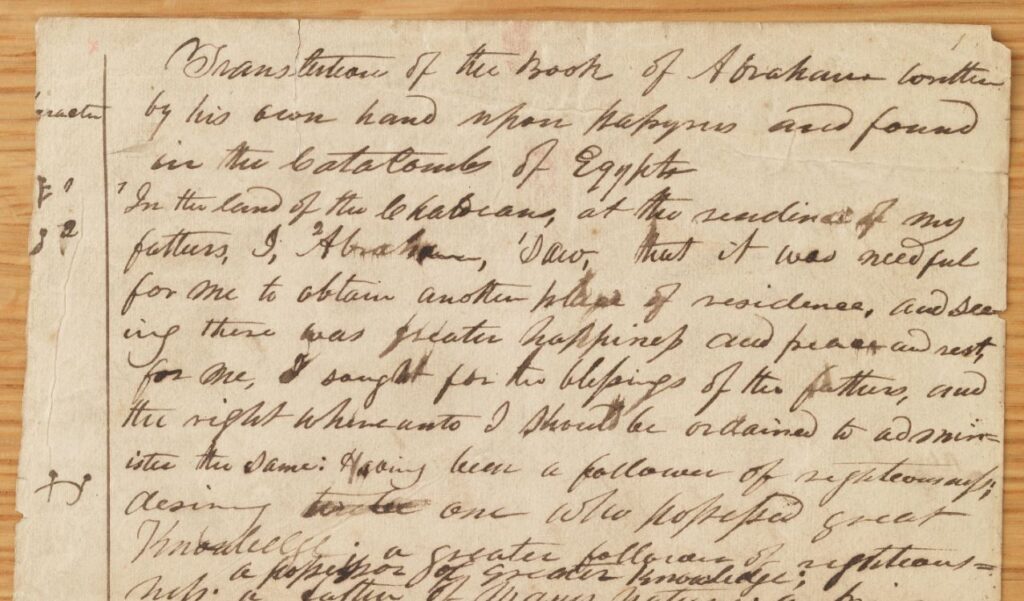

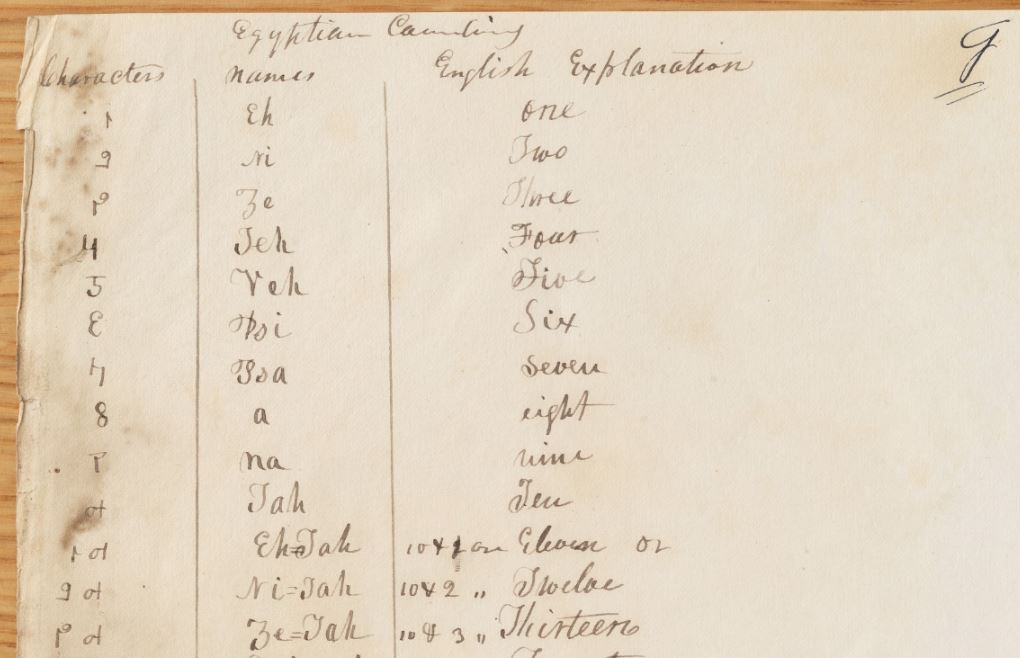

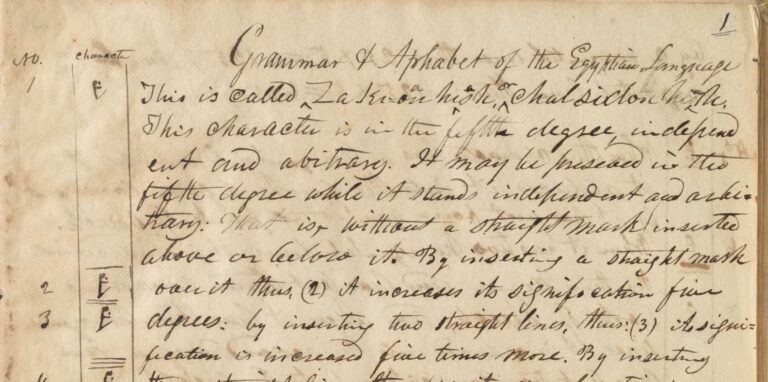

The GAEL (Grammar and Egyptian Alphabet) project found in the Kirtland Egyptian Papers are a collection of documents created between July and November 1835 that are closely connected to the early work surrounding the Book of Abraham. They include documents titled, The Egyptian Alphabet, the Egyptian Grammar, and the Egyptian Counting document, along with several Book of Abraham manuscripts with symbols written in the margins.

What are the Kirtland Egyptian Papers?

For many years, critics of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have claimed that the Kirtland Egyptian Papers were fake evidence Joseph Smith fabricated to make it look like he was actually able to translate the Egyptian Papyrus.

According to the critics, The Grammar and Egyptian Alphabet prove Joseph Smith could not translate Egyptian and therefore made up the Book of Abraham. The argument assumes these documents were used by Joseph Smith to translate the papyrus and that their failure shows deception or incompetence.

The Kirtland Egyptian Papers Were Not a Translation Tool

Evidence shows that these papers were definitely not used to translate the Book of Abraham. Like all of Joseph’s other translations of sacred texts, this translation was by the gift and power of God.

Scholars note that when Joseph Smith first received the papyri in Kirtland, he and his associates worked immediately enough that portions (“leaves”) of the Book of Abraham translation were already produced by the next day, which Oliver Cowdery read aloud.

The Book of Abraham is not a long book. It is only 5 chapters. Only 13 pages. A significant portion of it was translated immediately.

The Kirtland Egyptian Papers GAEL (Grammar and Egyptian Language) project began after Joseph Smith had already received the translation of portions of the Book of Abraham by revelation. The GAEL documents depend on already-existing scripture. They did not produce it which reverses the process that critics try to claim.

The Book of Abraham Came First

Detailed analysis of the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar project show that their explanations depend on the English text of the Book of Abraham, especially chapters 1 through 3. The vocabulary used in the documents closely matches Abraham but does not match comparable Genesis passages. This indicates the authors already knew the Abraham text.

William Schryver demonstrated this by analyzing the vocabulary statistically and contextually. Over 90 percent of the meaningful words in the Alphabet explanations appear in Abraham 1 to 3, but not in Genesis 12 or 15.

The documents known as Alphabet and Grammar were created after the Book of Abraham text already existed.

Theory of Kirtland Egyptian Papers as a Rosetta Stone

Hugh Nibley and other respected Latter-day Saint Egyptologists proposed that the Kirtland Egyptian Papers represented an effort to work in the opposite direction. In this view, the Book of Abraham was used to reverse engineer a kind of Rosetta Stone, allowing the meaning of Egyptian characters to be learned from an already existing English text.

Under that assumption, the conclusion was that the effort failed. The characters and sounds assigned do not match known Egyptian, and the system does not reflect accurate scholarship. This view does not challenge Joseph Smith’s prophetic role, but it does suggest that Joseph Smith, Phelps, Cowdery, and Parrish, were not skilled Egyptologists and that their attempt to construct something like a Rosetta Stone.

Pure Language Theoy

Others theories have speculated that W. W. Phelps’s “Pure Language” project was an attempt to recover or reconstruct an original, Adamic language spoken before the Fall. Influenced by biblical passages and early Latter-day Saint ideas about a divinely given language, Phelps explored the idea that ancient languages—especially Hebrew and what he called “Egyptian”—preserved fragments of this primal tongue. The project was less about scholarly linguistics and more about seeking a sacred, symbolic language capable of expressing divine truths more perfectly than ordinary speech.

The Kirtland Egyptian Papers Were Never an Attempt to Translate

William Schryver’s research challenges that assumption entirely. He argues that the Kirtland Egyptian Papers, including the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar, were never intended to function as a Rosetta Stone or as a tool to decipher Egyptian.

Instead, his conclusion is that the project served a different purpose, focused on symbolic representation and internal use rather than linguistic translation.

Schryver’s research points to the project, largely driven by W. W. Phelps, as the development of a cipher or coding system used to organize and share sacred doctrine, not an attempt to translate the papyri.

This GAEL project functioned as a coded system, not as a method for translating Egyptian, but as a way to organize, preserve, and selectively share advanced doctrine among a small group of trusted believers at a time when the Church had already suffered real consequences for revealing too much, too fast.

But why a coded system for sharing revealed doctrine?

Pure Language to Understand Eternal Truth

I have a theory of what the goal of the GAEL project was.

It relates, at least in part, to the idea of a “pure language.” But what did pure language actually mean?

Zephaniah 3:8-9, speaks of God restoring to the people a “pure language” so they may “call upon the name of the Lord.”

For the early saints, pure language may have been associated with God’s mode of communicating eternal realities with his covenant children. The Doctrine and Covenants, especially Sections 88 and 93, are full of references of receiving “light and truth” as the language of personal revelation from God.

For me, when I receive revelation from God while studying scriptures, it is often very difficult for me to articulate these truths into English to share with my family and Sunday School classes. I think many others struggle with this as well. We receive light, truth, love and knowledge, but just can’t share it the same way we think and feel it.

Joseph Smith was seeking a restoration of all truth—not just Christ’s New Testament Church, but a restoration of ancient truth, back from the beginning. In an 1832 letter to WW Phelps he expressed frustration with the limits of written language and its inability to convey spiritual truth and divine understanding. wrote,

Oh Lord God, deliver us in thy due time from the little narrow prison almost as it were of total darkness of paper and pen and ink and a crooked, broken, scattered and imperfect language.

We also know that the Book of Abraham introduces significant doctrine with strong parallels to temple worship and the endowment. When we have received light and truth, sometimes symbols can help us better understand that truth better than words.

My theory is that the GAEL project was an early attempt to express and share temple doctrine within a structured framework before temples were available.

The GAEL Project: Pre-Temple Doctrinal Framework

The Kirtland Egyptian Papers reflect an early attempt to organize a way to share sacred doctrine in a safe, controlled, symbolic way before temple worship existed.

The use of layered meanings, restricted interpretation, and compressed symbols points to a brainstorming phase in which deep doctrine and complex ideas could be preserved for a small circle, line upon line, without public exposure or the consequences that had followed from sharing new doctrine too quickly.

As temple ordinances later provided a ritual framework for conveying these truths, the need for a written symbolic system became obsolete.

Historical Events Supporting This Theory

Let’s review some of the events in history that support this theory.

- February 1832: Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon receive “The Vision” that became Doctrine and Covenants 76

- Spring 1832: Backlash follows, including apostasy and violence. Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon are dragged from John Johnson’s home in Hiram, Ohio, beaten, tarred, and feathered by a mob

- 1833: Severe persecution of the Missouri Saints and expulsion from Jackson County

- 1834–1835: Preparations begin for the publication of the Doctrine and Covenants, which includes section 76 and 88.

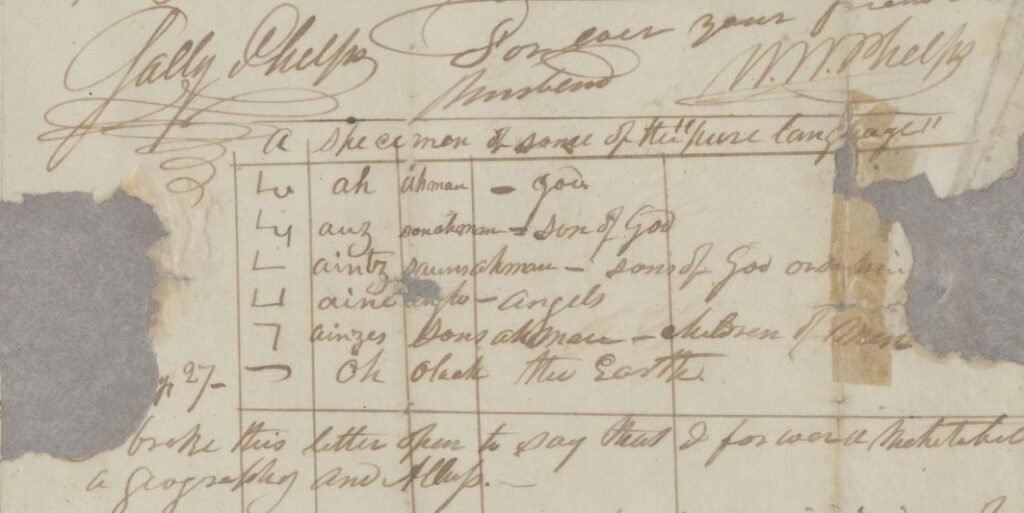

- May 1835: Phelps writes a letter to his wife showing a table of “A specimine of some of the pure language” with characters that represent meaning.

- July 1835: Michael Chandler arrives in Kirtland with mummies and papyri

- July 1835: Joseph Smith begins translating the Book of Abraham

- July to November 1835: Work begins on the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar Project

- August 1835: Doctrine and Covenants is published

- Fall 1835 to early 1836: Egyptian Alphabet & Grammar expansions continue by Phelps and Parrish

- January 21 1836: First Washings and Anointing’s performed in Kirtland Temple.

- March 27, 1836: Kirtland Temple Dedicated

- March 1, 1842: First part of Book of Abraham published in Times and Seasons

- May 4, 1842: First Endowments Performed in Red Brick Store

- May 15, 1842: Abraham 2-5 published in Times and Season

The Fallout from Doctrine and Covenants 76

A catalyst for the need to reserve sacred doctrine for symbolic and private settings may have occurred after the backlash that followed Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon receiving “The Vision,” now known as Doctrine and Covenants 76, in 1832.

This revelation taught ideas that directly contradicted mainstream Christianity:

- There is no endless hell

- Multiple kingdoms of glory

- Temporary punishment after death

- Salvation for nearly all humanity

- Glory based on law and knowledge

The reaction was intense. Many embraced the revelation and found hope in it, especially in contrast to the Calvinist ideas that prevailed at the time. Others struggled with it and concluded that Joseph Smith was a fallen prophet.

Joseph Wakefield, a high priest and missionary, rejected the revelation and left the Church, later opposing Joseph Smith publicly. Many Saints wrestled with the doctrine, and critics pointed to it as evidence of heresy.

Brigham Young later acknowledged that the revelation contradicted everything he believed at the time and that it took him years to fully accept it.

Only weeks after the revelation, Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon were attacked by a mob. Joseph was beaten and tarred and feathered. Sidney was beaten so severely that he was delirious for days. These events occurred in the same period when the doctrines revealed in the vision were provoking strong opposition.

Sharing new doctrine amongst a church that consisted entirely of new converts was causing real harm.

Coding Was Already Being Used

By 1834, Church leaders were using coded names in revelations to protect people and sensitive information.

Doctrine and Covenants 104 used substitute names such as:

- Enoch for Joseph Smith

- Ahashdah for Newel K. Whitney

- Olihah for Oliver Cowdery

- Shinehah for Kirtland

These were practical substitutions, not symbolism. For the protection of the living people that these revelations involved.

William W. Phelps and the Push Toward Symbolic Systems

William W. Phelps was the primary author of the Egyptian Grammar documents, and likely the mastermind behind the project. Nearly all pages are in his handwriting, with minor later additions by Warren Parrish.

Persecution in Missouri

W.W. Phelps understood firsthand the consequences of public language. His 1833 article on “Free People of Color” in the Evening and the Morning Star was the catalyst that lead to mob violence and the expulsion of the Saints from Jackson County, Missouri. The words he wrote were misundersthood and the saints suffered greatly because of them.

Desire to Create Symbolic Pure Language

Phelps also had an interest in this “pure language” that he and Joseph had previously discussed. In a letter to his wife Sally dated May 1835, more than a month before the papyri arrived in Kirtland, Phelps included a table of invented characters tied to doctrinal meanings. He labeled it “a specimen of some of the pure language.”

His concept relied on character-based symbolic encoding. The characters used in this letter resemble Masonic glyphs or symbolic shorthand common in Masonic coding systems. This was before the arrival of the Egyptian papyri in Kirtland, showing that Phelps’s work on the symbolic “pure” language project was already underway and was not prompted by the papyri themselves.

What the Kirtland Egyptian Papers Actually Are

The Kirtland Egyptian Papers have four different elements to them:

The first part of this video explains these documents very clearly and shows visuals making them easier to understand.

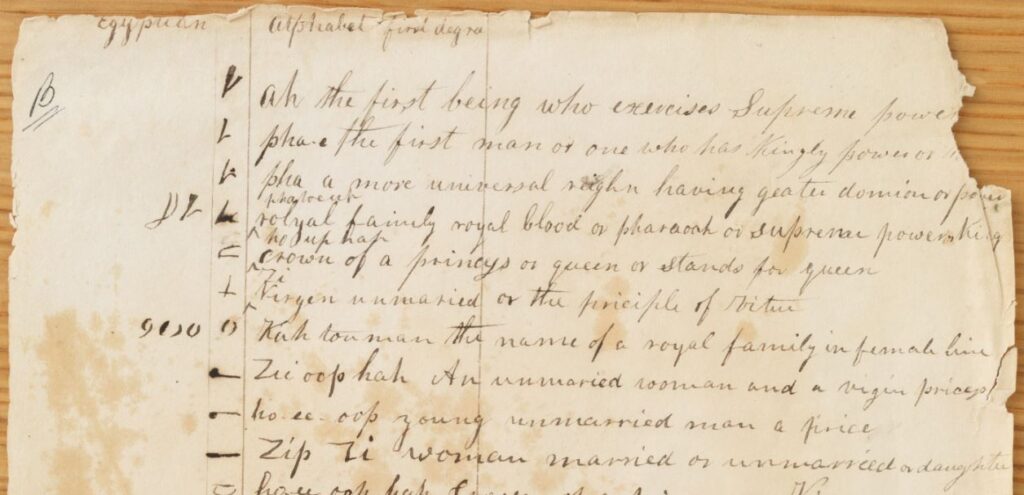

Egyptian Alphabet

The Egyptian Alphabet appears to have been a shared project involving at least Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and W. W. Phelps. All three of these brethren have similar pages titled “Egyptian Alphabet” primarily in their own handwriting. Each page is organized into three basic columns.

The first column contains a symbol or character, most of which are not Egyptian and do not come from the papyri. Several of these characters were the same ones that Phelps had already developed in his letter to his wife that are also used as the freemason Cipher. In the Egyptian Alphabet document these same characters have different meetings than in Phelps letter to his wife.

The second column gives a sound, name, or short word associated with that character.

The third column explains what the character represents, often in the form of a doctrinal idea rather than a simple definition.

The Egyptian Alphabet document appears to be the “1st Degree” of this coding simple, or the simplest form, the lowest level of meaning for each symbol.

Joseph Smiths Role in the Egyptian Alphabet

The three surviving copies show clear differences in role and development. Joseph Smith’s copy is the least developed in terms of written explanation, with pages that mostly list characters and brief labels and very little elaboration. This pattern suggests he was involved at an early stage by providing the core doctrinal framework that needed to be included, likely outlining the key ideas as the prophet and revelator.

The expansion, refinement, and systematizing of those ideas appear to have been carried out by his scribes. Joseph’s copy reflects oversight and direction rather than detailed authorship, with no indication that he was attempting to fully develop or formalize the symbolic system himself. Oliver’s copy contains longer explanations and Phelps is the most complete and developed.

This “Alphabet” seems to have been worked on after only the first part of the Book of Abraham was translated. It’s not an alphabet at all, includes many characters that are not Egyptian. Naming this document the “Egyptian Alphabet” would confuse someone looking for a coding decipher guide.

If what we have is all the work they did on the Alphabet portion of the project it appears that they abandoned that step because there were just far too many possibilities of words and meanings to worry about learning a coding system for the lesser first degree.

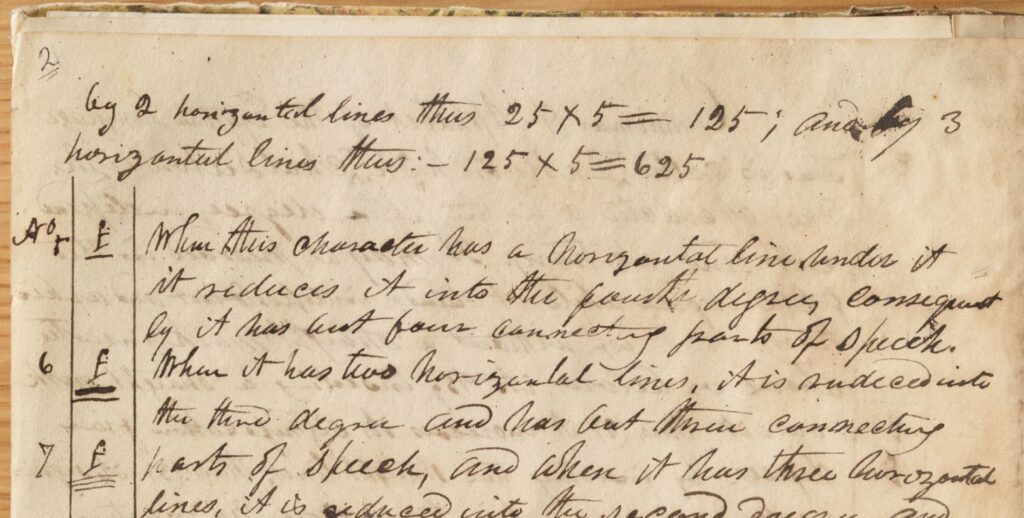

Egyptian Grammar

The Egyptian grammar appears to be an expansion of the Alphabet. Yet when I look at it and compare it to the copies of the Alphabet we have, there are many symbols in it that I can’t find on the Alphabet. The Egyptian Grammar utilizes meanings layered in degrees, where a single character can represent a sentence, a paragraph, or an entire doctrine.

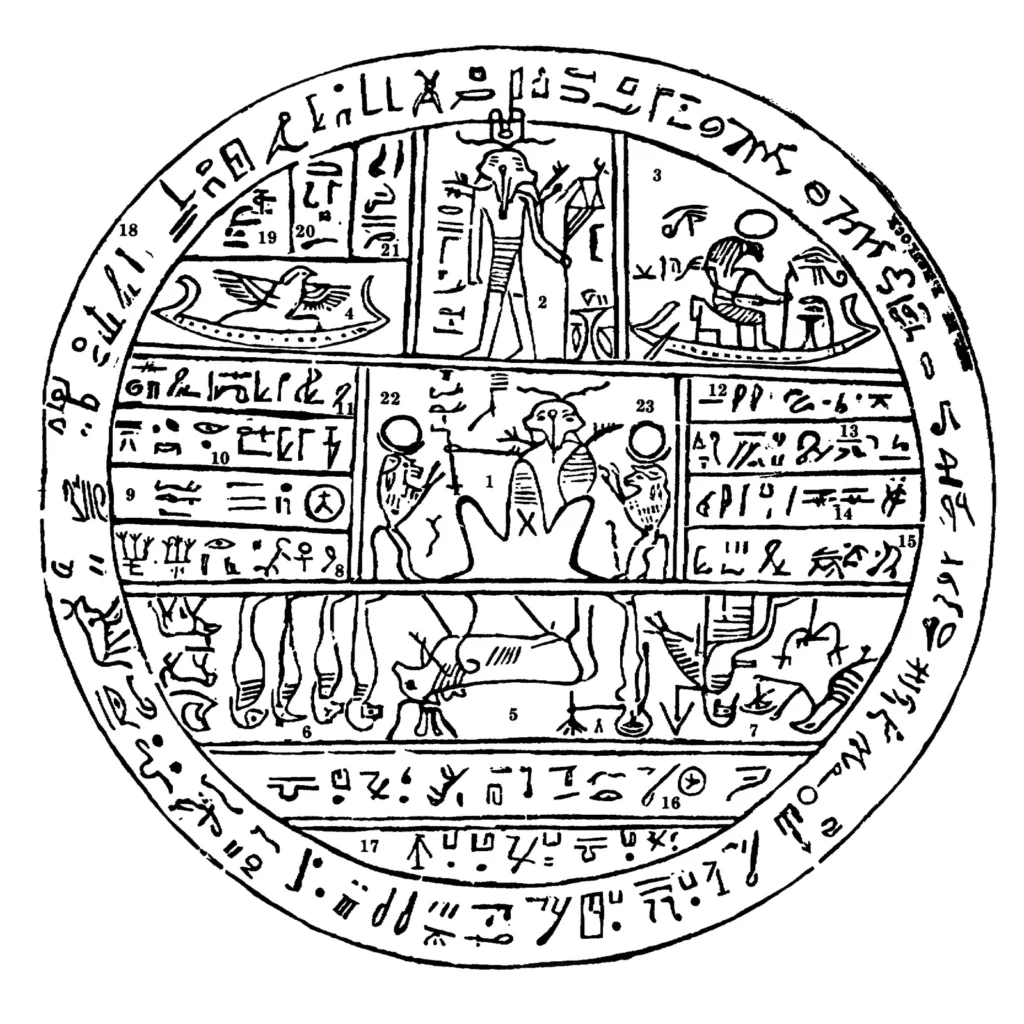

The beginning of the Egyptian Grammar pages discusses how one line below the character puts it in the 4th degree, twi lines 3rd degree, and three horizontal lines it is the 2nd degree. This document relied on the entirety of the translated Book of Abraham including facsimile 2 to provide expanded degrees of meaning using the coding system being developed.

The Egyptian Grammar takes the ideas introduced in the Alphabet and pushes them into a structured system of expansion. Instead of assigning a single meaning to a symbol, the Grammar lays out multiple degrees of meaning for the same character, moving from short definitions to long doctrinal explanations.

These expansions closely follow existing revelations, especially the Book of Abraham and sections 76 and 88 of the Doctrine and Covenants. The content shows that the doctrine already existed and was being reorganized, layered, and systematized rather than discovered through translation.

Unlike the Alphabet, which functions like a key or index, the Grammar functions like an interpretive framework. It shows how one symbol could stand for an entire chain of ideas depending on the level or degree being invoked. This fits a symbolic or coded system where meaning is controlled by context and shared understanding. The Grammar is almost entirely in Phelps’s handwriting, which supports the idea that he was the primary architect of the system. Its level of organization and completeness also suggests it was written after the Alphabet and represents the most mature stage of the project.

Page 4 of the Egyptian Grammar document appears to be what William Clayton assumed was Joseph Smith’s translation of the hoax Kinderhook plates in 1842.

Egyptian Counting

The Egyptian Counting document assigns made-up symbols next to English number words and shows how they can be combined to represent larger numbers. The meanings clearly come first and the symbols are added afterward, which is the opposite of translation. Because the same substitution pattern appears in the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar, this document strongly shows the project was about encoding information into symbols, not translating Egyptian. Not about Egyptian numbers or counting. The Egyptian counting is a way to code numbers so that they can be shared by only those that understand the code.

Abraham Manuscripts

How the Coding System Worked

The system organizes doctrine symbolically. Characters act as containers for ideas rather than words. Meanings expand by degree. The same character can represent different levels of meaning depending on context.

This approach fits early nineteenth-century ideas about ancient languages, where one symbol could convey entire concepts. It also aligns with cipher systems used in Masonic and esoteric traditions familiar to Phelps.

Calling the system “Egyptian” likely served two purposes. It aligned with beliefs about ancient sacred language, and it acted as a cover. A document titled “Egyptian Grammar” would attract less attention than one openly labeled as a doctrinal code.

The Doctrines in a Symbolic Language

The Grammar encodes doctrines that were considered sacred, controversial, and or would soon become published and thus available to the public. The major topics of the GAEL project were:

1. Divine Authority and Priesthood

Core idea: Authority originates with God and is passed down through appointed lineage and covenant.

Supporting elements found in the Alphabet and Grammar:

- Right of the firstborn

- Patriarchal authority

- High priesthood

- Authority passed from the fathers

- Appointment before the foundation of the world

- Foreordination

- Lawful heirs to priesthood

- Governance established by divine decree

Primary scriptural sources:

- Book of Abraham 1:2–4; 1:18–19

- Doctrine and Covenants 84

- Doctrine and Covenants 107

2. Kingdoms of Glory and Divine Law

Core idea: Heaven is structured, lawful, and hierarchical rather than binary.

- Celestial, terrestrial, and telestial kingdoms

- Kingdoms governed by different laws

- Glory differing “one from another”

- A kingdom that is not a kingdom of glory

- Beholding or not beholding the face of God

- Temporary suffering followed by inheritance

Primary scriptural sources:

- Doctrine and Covenants 76

- Doctrine and Covenants 88

3. Premortal Existence and Foreordination

Core idea: Human identity and calling precede mortal life.

- Spirits existing before the world

- Being chosen or appointed before birth

- Councils before creation

- Intelligence existing independently

- Spirits differing in knowledge and capacity

Primary scriptural sources:

- Book of Abraham 3

- Doctrine and Covenants 93

4. Governance, Order, and Cosmic Hierarchy

Core idea: God governs through order, councils, ranks, and delegated authority.

- God as supreme governor

- Princes, rulers, and governing heads

- Councils of authority

- Laws governing worlds and kingdoms

- Degrees of responsibility

- Order established before creation

Primary scriptural sources:

- Book of Abraham 3:21–28

- Doctrine and Covenants 121

5. Knowledge, Light, and Progression

Core idea: Growth, salvation, and glory are tied to knowledge and obedience to law.

- Intelligence and light

- Knowledge increasing by degrees

- Progression through obedience

- Understanding time, creation, and order

- Teaching, preaching, and spreading truth

Primary scriptural sources:

- Doctrine and Covenants 88

- Doctrine and Covenants 93

- Book of Abraham 3

6. Sacred History and Covenants

Core idea: God works through covenant families and sacred history.

- Abraham as a chosen patriarch

- Covenant lineage

- Seed and posterity

- Nations and inheritance

- Gospel preached to the heathen

- Preservation of priesthood through lineage

These doctrines appear in compressed form, often assigned to single characters.

They match Doctrine and Covenants 76, 88, 93, and the Book of Abraham.

Facsimile 2 and the Symbolic Framework Behind the Egyptian Papers

Facsimile 2 of the Book of Abraham helps clarify what the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar project appears to have been doing. Both Facsimile 2 and the GAEL use the same core terms, including degrees, governing power, time, light, intelligence, creation, and authority. In both cases, these words are not used to define Egyptian vocabulary or grammar. They are used to explain doctrine.

Symbols That Expand by Degree

One clear example appears in the GAEL’s treatment of time and motion. The Grammar states that one “cubit” of time equals three days, and that motion increases or decreases according to degrees. Kolob is described as first in motion, with its movement measured by multiple cubits. This is not presented as an Egyptian translation. It functions as a doctrinal model explaining how time, motion, and authority operate differently depending on rank and proximity to God. The same idea appears in Facsimile 2, where governing bodies preside over others and time varies according to position.

Facsimile 2 presents the universe as a structured system of levels. Some powers are closer to God, govern others, and operate according to a higher order of time and authority. Meaning is not flat or uniform. It depends on position. The closer something is to God, the greater its light, knowledge, and influence.

The GAEL reflects the same framework, but in written form. Instead of translating words, it assigns layers of meaning to symbols. A single symbol can represent a simple idea at one level and a much broader doctrinal concept at another. Meaning expands by degree rather than by sentence structure. This is not how a spoken language works, but it is how symbolic instruction works.

Symbols, Not Sentences

The shared structure of Facsimile 1 and the GAEL supports the view that the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar were not an attempt to decipher Egyptian, but an early effort to organize and transmit sacred cosmological doctrine in symbolic form.

Conclusion: Between Revelation and Temple Worship

Evidence points to a historical explanation for the Kirtland Egyptian Papers. As new revelations introduced unfamiliar and controversial doctrine, Joseph Smith and his colleagues appear to have sought a careful way to symbolize and share sacred ideas at a time when temple worship was not yet available. Earlier backlash and persecution had already shown the risks of saying too much too plainly, especially as revelations moved toward wider publication.

The Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar organized revealed restoration doctrine into characters, layers, and degrees, allowing meaning to be compressed and shared only with those who already had context. A single symbol could represent an entire concept, with meaning expanding by degree as understanding increased. This reflects a symbolic approach suited to a period when doctrine was transmitted mainly through text and speech, where ideas were easily taken out of context or misunderstood by those not prepared for them.

The project was never completed, taught publicly, or canonized. It appears briefly and then disappears as temple worship began in Kirtland and later developed more fully in Nauvoo. Ordinances, covenants, ritual action, and sacred space provided a stronger and more stable framework for conveying the same complex ideas. In this light, the Kirtland Egyptian Papers look less like a mistake and more like a transitional effort to safeguard and structure sacred doctrine until the temple became the primary setting for its transmission.

The Rosetta Stone – The Ancient Relic Not Related to The Book of Abraham

Book of Abraham Facsimile 1

Understanding What The Book of Abraham Facimilies Are

Book of Abraham – Evidence Joseph Smith Could Not Have Known

The GAEL Project – Pre-Temple Doctrine Coding?

Doctrine of the Book of Abraham

What is the Book of Abraham?

Continue reading at the original source →