The Know

In September 1857, a wagon company from Arkansas that was passing through southern Utah on its way to California was attacked, and eventually every member of the company (except seventeen young children) was slaughtered by Latter-day Saints at a place called Mountain Meadows.1 This tragic and senseless act of violence was inexcusable and contrary to the principles of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Some have tried to use this event as evidence that Latter-day Saints are violent people or that our faith tradition is inherently violent. The truth is much more complicated.

Violence is, tragically, an all-too-common part of mortal life in this fallen world. Recent years alone have witnessed riots, mass shootings, and war. Such violence is endemic to the human condition. Too often, regular people get swept up in the heat of a moment, and a specific set of conditions leads typically good people to commit unspeakable acts of violence. Regrettably, Latter-day Saints have not been immune to this common human problem.

Violence was an especially prevalent reality on the American frontier in the nineteenth century, where it was often directed toward minority groups, including religious minorities, who were unfairly perceived as the source of various social ills.2 As such, Latter-day Saints were regularly victims of violence in the 1830s and ’40s.3 Incidents like the Hawn’s Mill Massacre, which was set amid the violent expulsion of Latter-day Saints from Missouri,4 and the later martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith followed by another violent expulsion—this time from Illinois—had a generational impact upon the Latter-day Saints who endured these injustices and lost loved ones either in the violence or its aftermath.5

At times, after repeated acts of violence against them, the Saints responded with violence of their own, which they saw as acts of self-defense. As one trio of historians noted, however, “The majority could take the law into its own hands with impunity, but when minorities employed the same approach or tried to fight back, it usually backfired.”6 Such acts of aggression tended to confirm the stereotypes about how violent and depraved the “Mormons” were and thus escalated the hostilities directed toward them. Still, according to D. Michael Quinn, “Mormon marauding against non-Mormon Missourians in 1838 was mild by comparison with the brutality of the anti-Mormon militias.”7

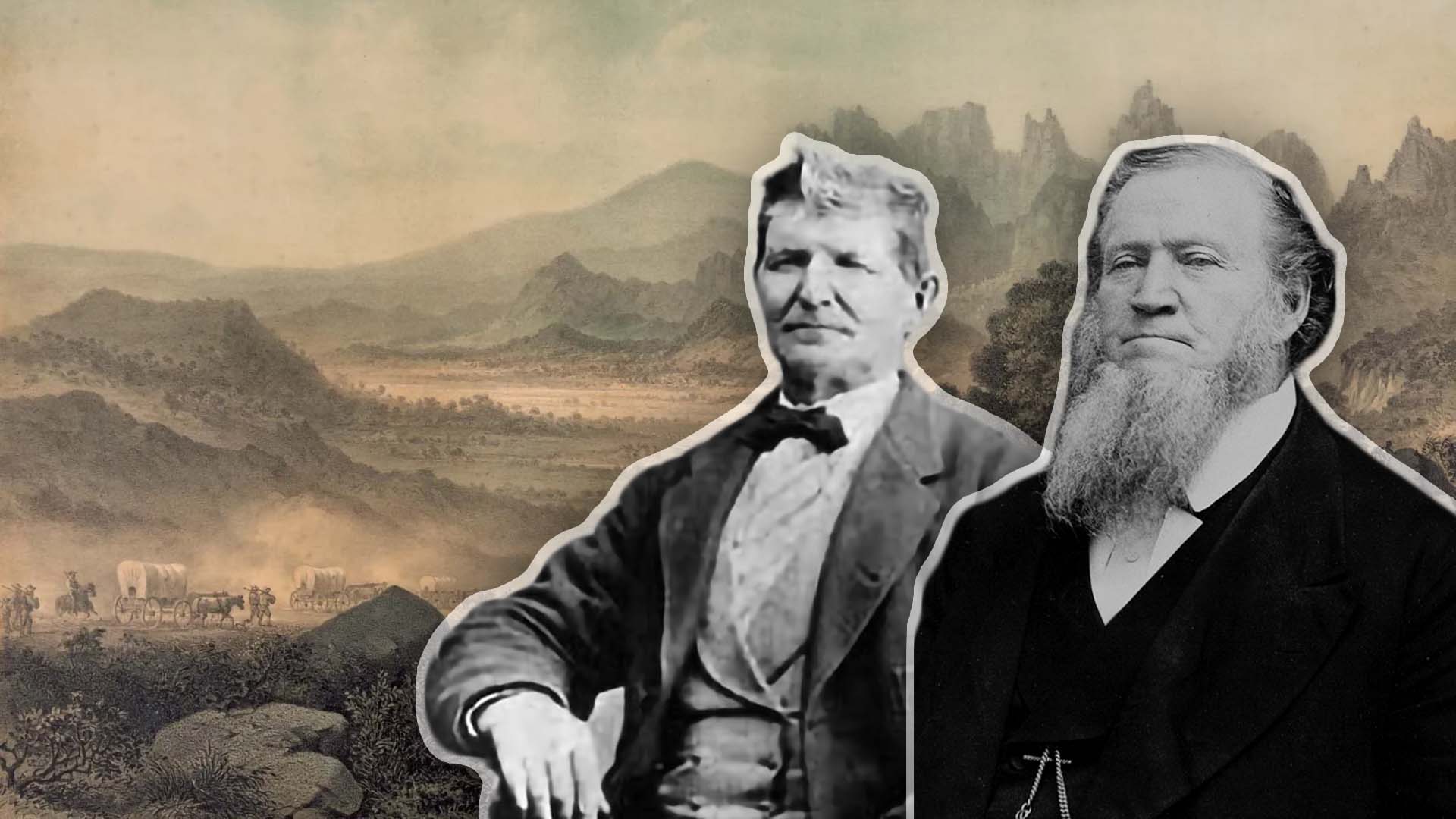

In Utah, the Saints were hoping to live and practice their religion in peace, but conflicts with outsiders continued, particularly with various territorial officials appointed by the federal government. These officials would then go back to Washington and spread rumors about the Saints, which stirred up further animosity.8 On July 24, 1857, word reached Utah of an approaching army sent by the US government.9 The intentions of this military force were initially unclear, but given the Saints’ past experience with violent persecution, many assumed the worst. The Saints began to prepare for war. Brigham Young and other leaders throughout Utah gave wartime speeches, rallying the Saints to defend themselves and encouraging them to store up any surplus grain, guns, and ammunition.10

Summer was also a time when many people emigrated, and by some reports an especially high volume of emigrants poured into California in 1857. Many wagon trains heading to California would pass through Utah, hoping to restock and resupply on food, ammunition, and other necessities in Salt Lake City and other towns along the trail. Although these wagon trains were generally good for the Utah economy, squabbles between the emigrants passing through and the settled population, including Native Americans, were not uncommon. The heightened tensions in Utah due to the wartime atmosphere served to magnify these petty conflicts in the minds of some of the Saints.11

As the Arkansas company made its way south through Utah Territory, its members repeatedly experienced frustrations trying to obtain needed food and other supplies, which most Saints were unwilling to sell them because of the counsel of their leaders to store up surplus resources in preparation for a potential war. As Ronald Walker, Richard Turley, and Glen Leonard explained: “At various points through the territory, the emigrants had a hard time getting the food and other supplies needed for their survival and comfort. Some vented their frustration in ways that made the Mormons—already apprehensive about the approaching army—feel even more threatened. At Cedar City the cycle reached a crescendo.”12

On the events at Cedar City, one group of writers explained: “Tempers flared when local mill operators demanded a cow in return for grinding the emigrants’ grain—an exorbitant price. Men of the Fancher party railed against the Mormon businessmen and threatened to join the approaching army and return to Cedar City to exact their revenge.”13 Some men reportedly went to the home of Isaac C. Haight, mayor of Cedar City, and threatened to send an army from California to kill Haight along with other local leaders and even Brigham Young.14 One account claimed that members of the party said they helped kill Joseph and Hyrum Smith and other Saints in Missouri and Nauvoo.15

Whatever the truth of these stories may be, there is no evidence that these were more than idle threats, “but in the charged environment of 1857, Cedar City’s leaders took the men at their word.”16 Haight sought permission from William Dame of Parowan, the highest-ranking leader of the local militia, to use the militia against the emigrants. Dame and the Parowan council instead advised Haight to not use force with the emigrants but to seek to maintain peace until they passed through the area.17

Haight ignored this counsel and hatched a scheme to get some of the local Paiutes to attack the wagon company at the Mountain Meadows. John D. Lee was recruited to persuade the Paiutes, who only agreed to do it if Lee led them.18 When Haight convened a council meeting in Cedar City to try to obtain approval for the attack, he was opposed by other local leaders, who forced him to agree to send a messenger to Brigham Young asking how to proceed.19 Before a messenger could be sent, however, an ambush was launched on the emigrants by Lee and some Paiutes. The wagon company circled their wagons in a defensive position and settled in for what became a five-day siege.20

A messenger was still sent to Brigham Young, but before he could return events began to spiral out of control. The emigrants became aware that it was not merely an attack by natives, but that Mormons were involved. Fearing the consequences if word got out that the Mormons had attacked a wagon train, Haight and others determined that they could not allow survivors to escape, but Haight felt he needed permission from William Dame to execute his deadly plan.21

Once again, a council was called in Parowan with Dame and other leaders. But these men did not approve an attack on the emigrants, and instead a plan was made to help the company continue on its way to California.22 Haight believed this was unacceptable. He and one of his counselors privately met with Dame and pressed upon him his fear that letting the emigrants survive to tell of the attack “would unleash aggression on the southern Mormon settlements.”23 Reports on exactly what was said and agreed to in this meeting are conflicting and uncertain, but Haight came away believing that he had Dame’s support for his subsequent actions.24

The plan was made to have John D. Lee approach the wagon train under the pretense of offering assistance. Lee would convince the emigrants to give up their arms and let the Saints lead them out of the meadow and into safety. Women and children would go first, followed by the men, who would each be accompanied by an armed militiaman. Instead of protecting the emigrants, however, the militiamen and some Paiutes killed all the emigrants except seventeen small children when a signal was given.25

Two days later the messenger returned with word from Brigham Young, telling Haight not to interfere or meddle with the emigrant train but “let them go in peace.” Upon receiving the message, Haight reportedly sobbed like a child saying, “Too late; too late.”26

The Why

It is difficult to fully grasp or understand why events like the Mountains Meadows Massacre happen. It can be easy and even comforting to assume that religious fanaticism caused this unspeakable tragedy; such an explanation makes it easier to process and dismiss. But according to historians, “For the most part, the men who committed the atrocity at Mountain Meadows were neither fanatics nor sociopaths, but normal and in many respects decent people.”27

It was not because of their religion but in spite of it that these men committed this abhorrent act of violence. The gospel of Jesus Christ calls upon disciples to “do good; seek peace” (Psalm 34:14) and “live peaceably with all men” (Romans 12:18). In His Sermon on the Mount, the Savior said, “Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God” (Matthew 5:9). He then taught His disciples to reconcile with adversaries (vv. 21–26), turn the other cheek (v. 39), and ultimately, “love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you” (v. 44).

In response to the first wave of persecution and mob violence directed against the Saints in 1833, Joseph Smith received a revelation instructing the Saints to “renounce war and proclaim peace” (Doctrine and Covenants 98:16) and to endure persecution patiently and seek to resolve conflicts peacefully before taking up arms in self-defense (D&C 98:23–37). On multiple occasions when local Church leaders from Parowan and Cedar City counseled together regarding the emigrant company at the Mountain Meadows, they encouraged actions that would prevent or deescalate the violence and promote peace. It was only by repeatedly ignoring the judicious and sound decisions of these councils that the massacre was brought about.

Speaking on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of this tragic event, President Henry B. Eyring said:

The gospel of Jesus Christ that we espouse abhors the cold-blooded killing of men, women, and children. Indeed, it advocates peace and forgiveness. What was done here long ago by members of our Church represents a terrible and inexcusable departure from Christian teaching and conduct. We cannot change what happened, but we can remember and honor those who were killed here.28

Studies have shown that the conditions that led to this tragedy were consistent with those found in other instances where seemingly normal people have committed mass killings.29 Thus, the source or cause of this massacre was not religion but something embedded deep within the fallen condition of humanity itself (see Mosiah 3:19; Ether 3:2). Only the Atonement of Jesus Christ can overcome this lost and fallen state and bring the peace and healing this world desperately needs.

Further Reading

Gospel Topics, “Peace and Violence among 19th-Century Latter-day Saints,” online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Glen M. Leonard, Massacre at Mountain Meadows (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Donald R. Moorman, with Gene A. Sessions, Camp Floyd and the Mormons: The Utah War (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1992), 123–150.

Richard E. Turley and Ronald W. Walker, eds., Mountain Meadows Massacre: The Andrew Jenson and David H. Morris Collections (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2009).

- 1. For a brief summary of the incident, see Casey Paul Griffiths, Susan Easton Black, and Mary Jane Woodger, What You Don’t Know about the 100 Most Important Events in Church History (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2016), 150–153.

- 2. Gospel Topics, “Peace and Violence among 19th-Century Latter-day Saints,” online at churchofjesuschrist.org: “In 19th-century American society, community violence was common and often condoned. Much of the violence perpetrated by and against Latter-day Saints fell within the then-existing American tradition of extralegal vigilantism, in which citizens organized to take justice into their own hands when they believed government was either oppressive or lacking. Vigilantes generally targeted minority groups or those perceived to be criminal or socially marginal. Such acts were at times fueled by religious rhetoric.”

- 3. For a summary of the violence perpetuated against Latter-day Saints from 1830 to 1846, see Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Glen M. Leonard, Massacre at Mountain Meadows (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2008), 6–19.

- 4. See Alexander L. Baugh, ed., Tragedy and Truth: What Happened at Hawn’s Mill (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2014).

- 5. For discussions of several of these violent incidents and their impacts on Latter-day Saint history, see Glenn Rawson and Dennis Lyman, eds., The Mormon Wars (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2014).

- 6. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 10–11.

- 7. D. Michael Quinn, The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1994), 99.

- 8. See Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 20–32.

- 9. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 33–40. For more on this army and the so-called Utah War, see Donald R. Moorman, with Gene A. Sessions, Camp Floyd and the Mormons: The Utah War (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1992).

- 10. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 41–73.

- 11. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 74–100.

- 12. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 134. For documentation of this cycle playing out along the trail, see pp. 101–128.

- 13. Griffiths et al., What You Don’t Know, 150–151.

- 14. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 133.

- 15. Griffiths et al., What You Don’t Know, 151; Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 133.

- 16. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 135–136.

- 17. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 136.

- 18. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 137–148.

- 19. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 155–157.

- 20. Griffiths et al., What You Don’t Know, 151.

- 21. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 164–174.

- 22. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 177–178.

- 23. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 174.

- 24. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 178–179.

- 25. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 189–209.

- 26. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 225–226. For the full contents of the letter, see pp. 183–186.

- 27. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 128.

- 28. Henry B. Eyring, “150th Anniversary of Mountain Meadows Massacre,” September 11, 2007, online at newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 29. Walker et al., Massacre at Mountain Meadows, 127–128.

Continue reading at the original source →